Book Review: Poet recalls stormy life growing up Rastafari in Jamaica and her struggle to break free

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/10/2023 (778 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

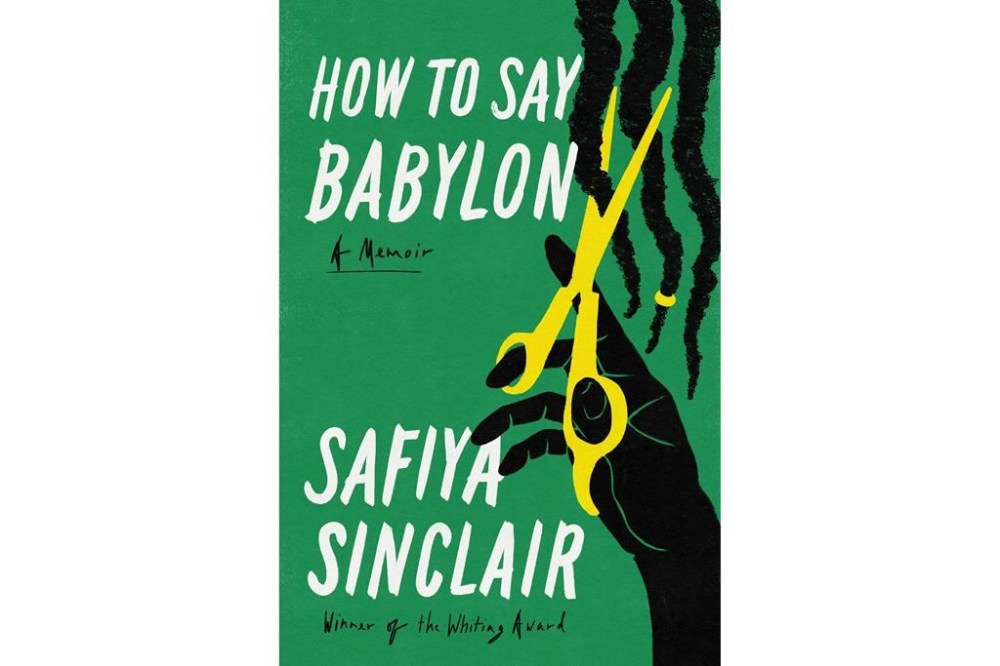

It’s not unusual for an autobiography to chart a person’s passage from rags to riches, ignorance to enlightenment, or bondage to freedom. It is unusual to find one as powerful and disturbing as Safiya Sinclair’s debut memoir, “How to Say Babylon,” which has already drawn comparisons to Tara Westover’s “Educated” and Mary Karr’s “The Liars’ Club.”

Sinclair, an award-winning poet who teaches creative writing at Arizona State University, grew up in extreme poverty in Montego Bay, Jamaica, in the shadow of the luxury hotels that cater to wealthy tourists. Her father, a reggae musician, was a militant follower of a strict Rastafari sect. Her mother, selfless, loving and subservient to her father, was Safiya’s lifeline, introducing her at a young age to poetry, which became her ticket out.

Sinclair writes of a chaotic yet magical childhood, moving constantly but always surrounded by lush tropical forests and broad vistas of sea and sky, which later gave her the sounds and imagery of her poems. “It was here, on our verdant hillside, that my mother first taught me the poetry of greenery. She showed me how to suckle language from each bloom.”

As a girl, she revered her father, nodding “Yes, Daddy,” whenever he delivered one of his endless rants about the evils of Babylon — Rasta shorthand for the white, western, Christian world — but her childhood idyll ended when she started menstruating and he deemed her unclean.

Eventually, this estrangement led her to question all the tenets of her fundamentalist upbringing, a process that was accelerated when she discovered that her sanctimonious father indulged in porn and cheated on her mother. School was her escape. She graduated high school at 15, published her first poem at 16, and found important mentors including the Nobel Prize-winning Caribbean poet Derek Walcott.

Ultimately, she was strong enough to break free of her father’s tyrannical grip, leading the way for her long-suffering mother and three siblings to do the same. Yet in something of a twist, she refused to sever ties with him completely, even thanking him for “instilling this steadfast rebel in me.”

Once she left home for college in America — the beating heart of Babylon — she began to understand how centuries of colonialism and slavery led to the extreme separatist beliefs of the repressive cult she was raised in. Though she ended up cutting off her dreadlocks, a symbol of Rasta life, she channeled her father’s rage at the injustices of Babylon into her own shimmering tapestries of words.

The Free Press acknowledges the financial support it receives from members of the city’s faith community, which makes our coverage of religion possible.