Overcoming grief of sudden loss an uphill struggle

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/06/2024 (504 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Young love — it’s a time of giddy romance and optimism, when a couple thinks ahead to the life they’ll build together.

When one of the partners dies suddenly and too soon, how the remaining person goes forward can involve traumatic, guilt-inducing decisions.

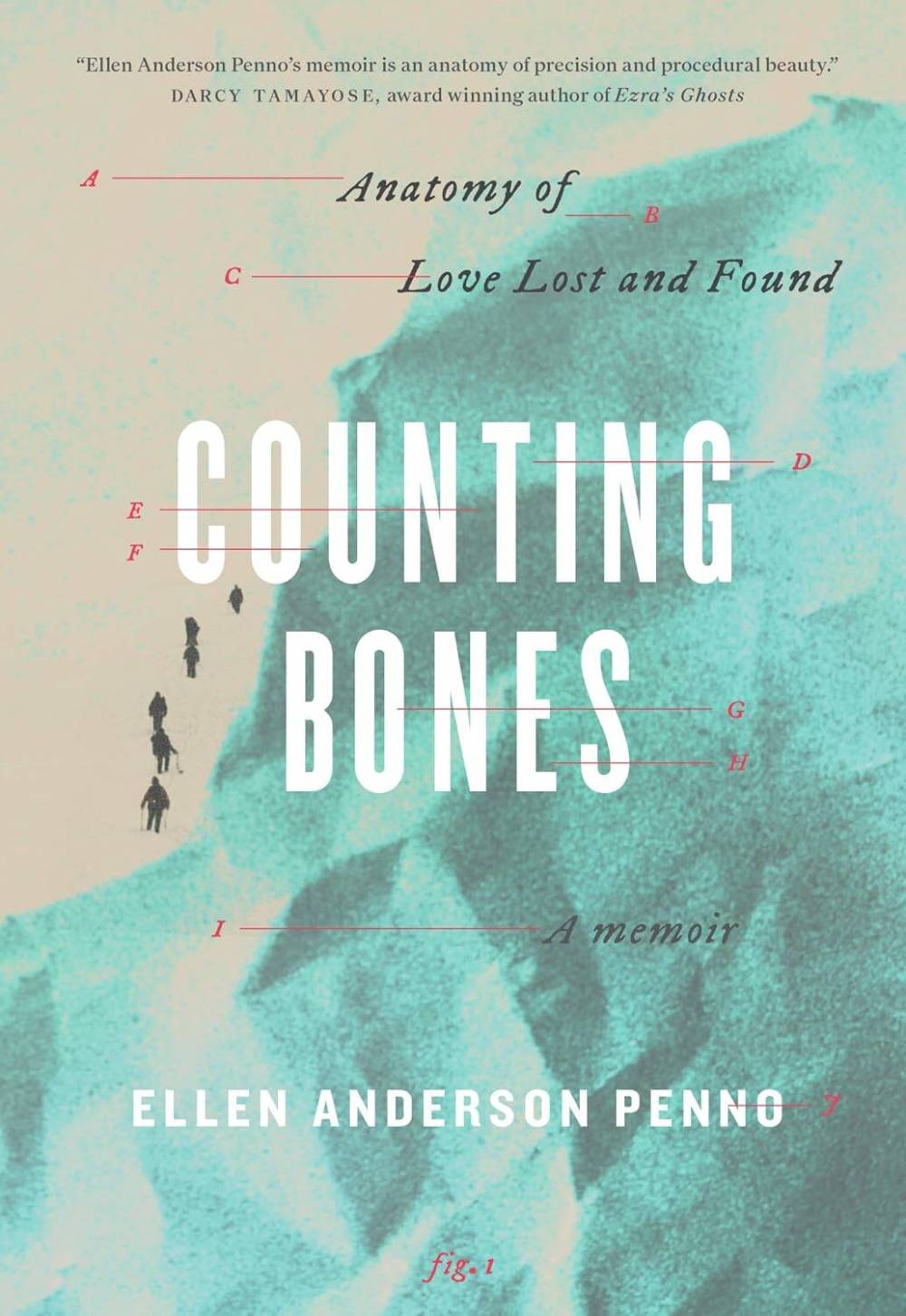

That was the situation Calgary ophthalmologist Ellen Anderson Penno found herself in when her first love, Ian Kraabel, was buried along with another man in an avalanche on Mount Baker in Washington state in August 1986. Penno was 24 years old then, and in her moving memoir of love and living, Counting Bones, now recalls how Kraabel’s death affected the rest of her life.

The shock of Kraabal’s death was made worse because he had been thrown into a crevasse by the avalanche; the attempt to recover his body had to be abandoned because it was deemed too dangerous. Penno had been accepted to medical school in Minnesota, scheduled to begin only a few weeks later. She knew the right thing to do was to begin her studies, but that didn’t make it any easier.

“In September, 1986, it rained cadavers,” Penno writes of her first year in medical school, when gross anatomy and human dissections form the basis of the curriculum. She said “grief encased (her) like molasses” — becoming an entity beyond her control. She describes how it welled up unexpectedly as she struggled through meeting new people and paying attention to her work. Carrying a skull locked in a case back and forth from her apartment to school, she was constantly reminded of the fragility of the human body. Death stared her in the face daily.

Penno’s memory of details is extraordinary — likely a benefit of her work as a physician, it probably added to her anguish.

She and Kraabel were adventurers, scaling ice fields and mountains as they built their relationship. Her recall of how climbs are meticulously planned and rehearsed in advance, how ascents are judged, which hands are best to grasp the pick, how to make a “finger jam,” belay ropes, etc. is a clinic for the uninitiated, a testament to the respect serious climbers have for the danger mountain climbing poses.

Nevertheless, nature is unpredictable.

The chapters on the aftermath of Kraabel’s death are particularly poignant. Penno references Gray’s Anatomy, the seminal textbook of medical science, dissecting her memories and exploring their wider meaning. She laces childhood events, history and science in with sorrow through her narrative, even as time seemed to stand still.

But she plowed through, trying to display the same bravado as her classmates while grappling with the punishing amount of studying, clinical practice and sleeplessness of medical school. A subsequent unsound relationship lasted too long, providing lessons she hadn’t anticipated because it was opposite to the positive bond she says she had with Kraabel.

Over time, Penno had two daughters and ran an eye clinic doing work that mattered, saving the sight of patients and changing their lives. She remained active physically, hiking and climbing in the Rockies.

But in 2014 the crevasse on Mount Baker spit out the backpack of the other person killed with Kraabel, pulling her back to that difficult time. She opened up boxes of letters and memorabilia long stored away in a closet. She began to remember — and to write.

Reading through newspaper clippings and their love letters brought back sad memories, Penno says, but writing about them proved to be positive. She says her life has been “punctuated by kindness.”

Penno still has Kraabel in her heart, and finds meaning in the line from Dylan Thomas: “Though lovers be lost, love shall not.”

Harriet Zaidman is a writer for young people and a freelancer living in Winnipeg.