Perilous prognosis

Cancer diagnosis and treatment chronicled in Matthews’ moving account

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/09/2024 (415 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

According to the Canadian Cancer Society, just under 250,000 people are diagnosed with cancer each year in this country (with around 84,000 dying each year). While diagnostic and treatment research has improved the outcomes for most, the word “cancer” uttered while sitting on a paper sheet in a paper gown can be a terrifying and life-altering moment.

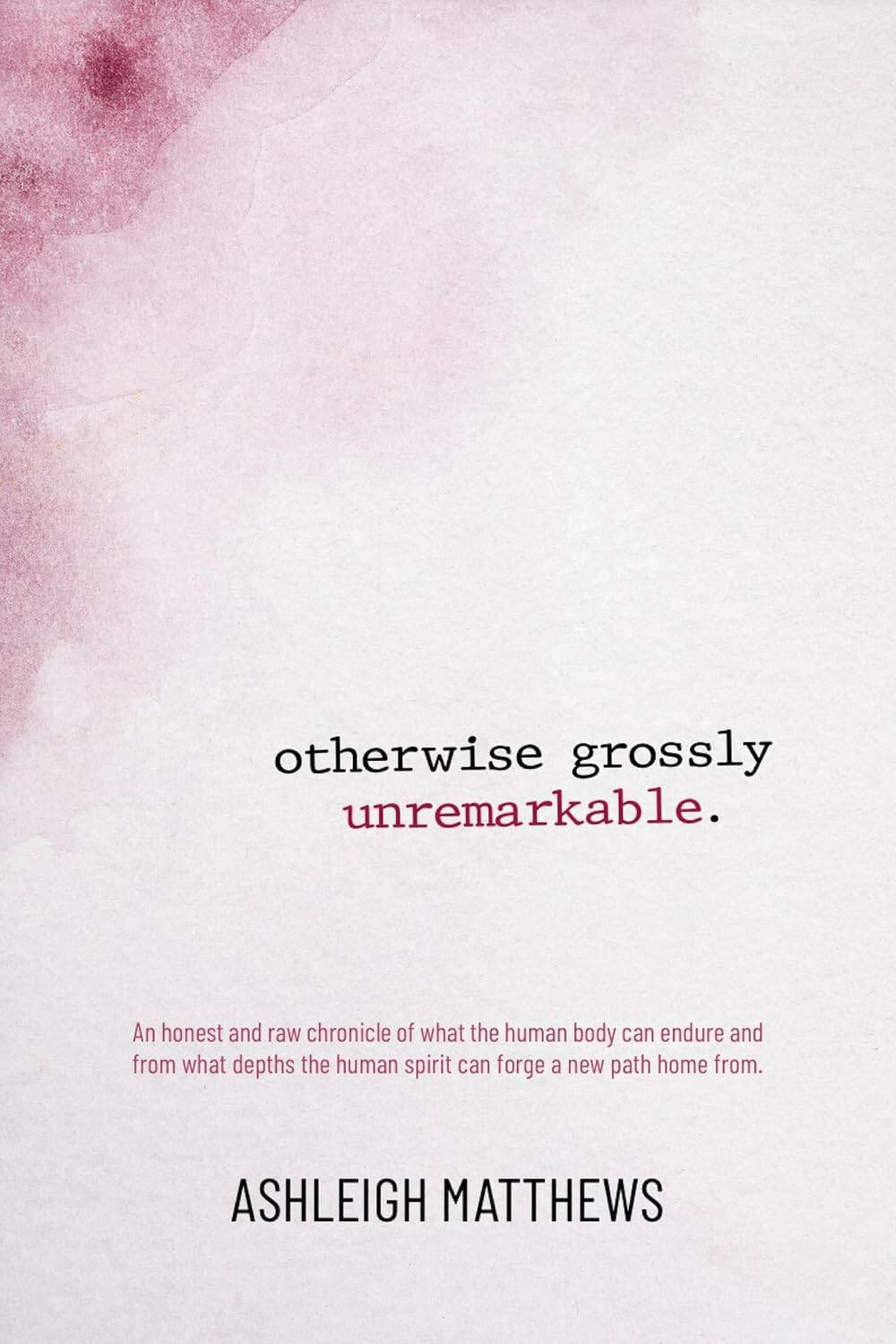

This reviewer knows — not only as a kidney cancer patient, but also as the partner of a breast cancer survivor. The existential smack to one’s life when a cancer diagnosis becomes reality is something that can never again be ignored. Such is the experience of Ashleigh Matthews — mother of two and breast cancer survivor — and author of Otherwise Grossly Unremarkable: A Memoir of Cancer.

Matthews, a homeschooling Newfoundlander, was first diagnosed in 2019 following her own discovery of a lump in her right breast in October. Disbelief was her and most cancer patients’ reaction, and following a botched ultrasound, her cancer was confirmed two months later.

Supplied photo

Ashleigh Matthews’ writing offers readers a glimpse into the peaks and valleys associated with the physical and emotional toll of a cancer diagnosis.

At 35, Matthews was statistically young to receive such an initial diagnosis, so that shock was amplified when she heard the news: “I sank to the floor and wailed. I don’t remember what (husband) Scott or my doctor said in the first few minutes… These parts of my memories are lost to the bulldozer of grief.”

Hearing the “C” word emanate from the mouth of a physician is a terrifying experience, and each person manages the existential shock in their own way. For Matthews, the debilitating news of “ductal carcinoma” (cancer that is situated in one place) was compounded with her incredible medical team’s curiosity about another cancer in her lymph nodes. This is the last thing anyone wants to hear.

Following ultrasounds, mammograms, MRIs, biopsies and various bone and CT scans — a testament to Canada’s incredibly responsive health care system when a cancer diagnosis is determined — Matthews was given the official word: “Stage 3, grade 3B, estrogen and progesterone-positive, HER2-negative multifocal invasive mammary carcinoma.” In other words, serious cancer that would require chemotherapy, radiation and surgery — a surgery where she would elect to have a bilateral mastectomy.

With a path of treatment set out by her crack team, Matthews eloquently (and with a healthy amount of potty-mouthed language) describes that feeling when the news of cancer and the unknown germinates: “Cancer is a black hole that pulls every single aspect of life into it. It obliterated my ability to function in its presence and it systematically destroyed whatever came nearest to it in my life during the weeks I spent waiting to find out whether I was a terminal cancer patient.”

Her treatment would involve five rounds of intensive chemotherapy — a treatment that essentially poisons the body with a cocktail of radioactive substances designed to eradicate quickly dividing cells. And despite the Herculean efforts of Cancer Care nurses — among the many hyper intelligent and caring researchers, nurses, health care aides and doctors in the business of saving lives in Canada — the experience for Matthews and other patients is nothing short of feeling drained, whipped, and tossed to the curb. The body is ravaged, and each subsequent chemo session knocks a loved one down a rung of normalcy. The energy-filled and vibrant love of your life becomes a tiny, hairless, curled-up ball of exhaustion.

For Matthews, the chemo trip was the most intense and difficult experience of her life: “The nature of riding the chemotherapy roller coaster is that you never climb quite as far back up after each plummet downwards, and eventually you just bottom-out and stay down.”

Hilarious at times, Matthews’ writing helps bring the reader into the peaks and valleys associated with minor celebrations, hardships of daily radiation and surgeries that would remove both breasts, lymph nodes and eventually her ovaries. Menopausal now at 37, her physical life was altered beginning with the utterance of the penetrating word of cancer.

Otherwise Grossly Unremarkable

But treatment is one thing. Another significant hurdle of a cancer diagnosis and treatment is living with the knowledge that you had it, and that you may get it again. As Matthews explains, “My body is free of cancer, but the magnitude of the damage left behind is why I often feel it is imprecise to say I ‘had’ cancer, to suggest it is behind me. My body, my life, is not free of the shockwave.”

The physical and emotional scars left by this cruel disease are humanized in Otherwise Grossly Unremarkable. Matthews’ experience and her generosity in sharing are small elixirs to those who have lost loved ones, who can’t stop thinking of cancer every five minutes and/or for those about to hear those awful words: you have cancer.

Matt Henderson is the superintendent of Winnipeg School Division.