A real education

Reflecting on the challenges of making U of W an anchor institution of the inner city

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/10/2024 (421 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

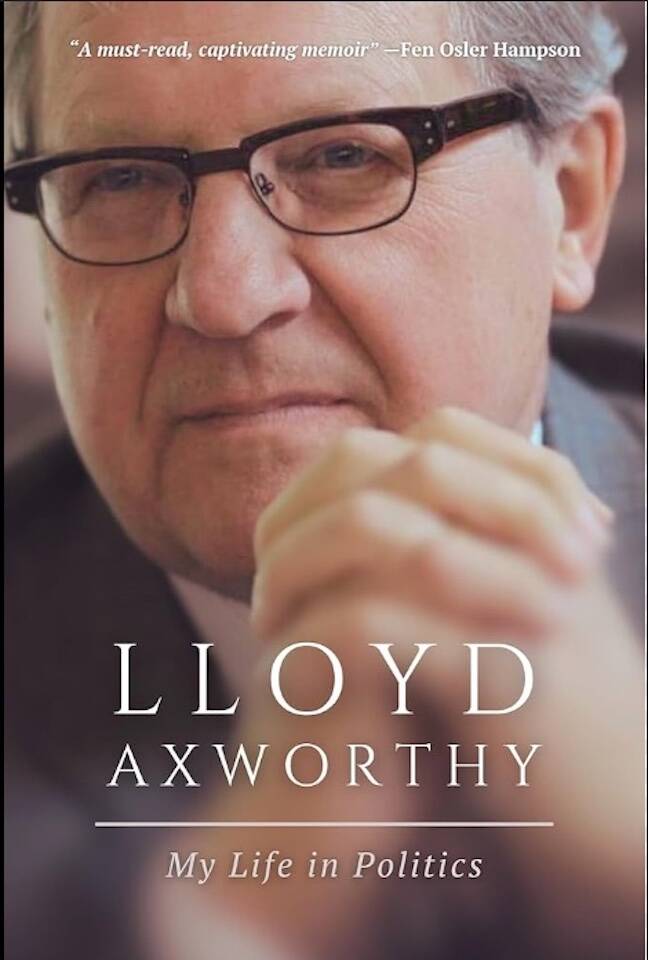

An excerpt from Lloyd Axworthy: My Life in Politics (Sutherland House). A book launch will be held Oct. 16 at McNally Robinson Booksellers.

Driving east from Victoria on the Trans-Canada in April 2004, listening to Eric Clapton on the car’s stereo system (before his anti-vax days), I had time to think about what being president and vice-chancellor of the University of Winnipeg had in store. It was not an unknown terrain.

I had been an undergraduate, assistant professor, director of the IUS (Institute of Urban Studies), honorary doctorate recipient and alumni donor at U of W. But, I never imagined becoming president for a 10-year, two-term tenure. How did that come about? Well …

The university was coping with a crisis. Constance Rooke, who had become president and vice-chancellor in 1999, was dismissed by the University Board of Regents in December 2002 over concerns about finance and proposed plans for expansion. The government of Gary Doer had raised alarms and there were internal disagreements over the direction of the institution. Dr. Rooke, a highly regarded literary figure in Canada, had run into opposition from some faculty and board members over her ambitious plans to broaden the scope of the university’s cultural and community reach and certain renovations to the president’s house on Oak Street. I had dinner in Toronto with Connie several months after I had taken office when she was ill with the cancer that would soon take her life, but still engaged and anxious to talk about her time at U of W.

She admitted that she hadn’t fully understood the local mores nor the politics of the university and ran afoul of pockets of resistance. Still, she believed that the university had the potential to grow beyond being a competent learning centre of undergraduate education into an engine of change in learning that reflected the reality of downtown Winnipeg.

I agreed.

It may have been that need to find someone with local grounding who led the search committee headed by the Vice-Chair of the Board of Regents, Carol Wylie, to contact me to see if I might be interested in applying. My answer was that I was too old and other-directed to enter an academic beauty contest. A few weeks later Carol got back with the suggestion that I forego the normal rigmarole and come to Winnipeg to meet with the board, the chancellor and key faculty.

In the meantime I had been receiving supportive messages from Premier Doer; Sandy Riley, the chancellor; and Susan Thompson, the new head of the University Foundation. On their urging and after talks with (my wife) Denise and with Paul Fraser, my longtime friend from United College days, I agreed to attend the meeting and discussions in Winnipeg. The exchanges must have worked. On Dec. 15, 2003, the Board of Regents unanimously passed my appointment and in April I was headed back to Winnipeg for a decade at the helm of my alma mater and a return to the city that I considered home. I viewed the job as one that offered the context and agency I was looking for — it was a microenvironment where ideas could be put into action, and it promised a culmination of my many years of interest in education in the inner-city.

Taking the reins as president in June, I decided to spend some time sussing out the extant situation of the university, starting with a canvass of faculty, staff and board members. This met with a mixed response. A faction in the faculty and admin were satisfied with the status quo.

There was a group with a far-left bias who didn’t welcome a president with an obvious liberal pedigree and made their opposition clear. They continued to kvetch for the next 10 years. There were other faculty and admin people brimming with ideas who urged me to become proactive in making the university an anchor institution in the inner-city. Support for recasting the role of the university in the city and province was expressed in my meetings with the premier, the mayor, and members of the downtown business groups and social agencies. They respected the long history of the institution as a learning centre but were worried that it had become too insular — an ivory tower, in other words.

The accuracy of that description was affirmed in what I heard from local residents when I went knocking on their doors. They saw the university as being aloof from them and their needs. Security restrictions prevented access by local people to the campus. There was a long-simmering resentment that the university’s Duckworth Athletic Centre, which had received provincial funding on the basis of shared use with the community, no longer was open to them. There was skepticism about the university making much difference in their lives.

I saw firsthand that the neighbourhood had serious pockets of poverty and a lack of services, housing and recreation facilities, which seemed to have little relevance to the university. Building trust with members of the community was a priority and a necessity.

Since the departure of Constance Rooke, the interregnum had been professionally handled by Patrick Deane, who has since gone on to be the chief officer at McMaster and Queens. He had started to rework the financial problem, especially paying back the pension fund. When I met with Susan Thompson from the newly formed University Foundation and its chair, Sandy Riley, they informed me of the parlous state of funding and the lack of any plans for a capital campaign. The Doer government had frozen tuition fees, capping any increase in revenue, and the university’s campus was in serious need of refurbishment.

The science labs were leaking fumes and in danger of city-imposed penalties. Classroom space was in short supply and there was limited student housing. The Wesley building and Convocation Hall were in dire need of renovation. Spence Street, a four-lane heavily trafficked thoroughfare bifurcated the west side of the campus — a risk to students crossing to the Duckworth and a barrier to any further development. (Ultimately, we had it closed and turned into a campus mall.) All to say that there was no lack of obstacles and muddles needing attention.

My experience with problem-solving in government over the years came in handy. I remember being challenged on what possible lessons I had learned in politics that had any relevance to the position of president of an academic institution. I was tempted to reply that I had learned to stoically put up with confrontational questions from pompous people. But I demurred and instead recited my academic credentials, my long association with the institution going back to being a student, and my support by way of being an annual donor and contributor to the institution. This cranky challenge reminded me that just as in politics, there would be those in opposition who would irrationally confront whatever they didn’t like.

Lloyd Axworthy served as an MLA in the Manitoba Legislature for six years before embarking on a 21-year career in the House of Commons, serving in the cabinets of Pierre Trudeau, John Turner and Jean Chretien. He returned to Winnipeg to serve as president of the University of Winnipeg for a decade. He currently chairs the World Refugee and Migration Council.