Japanese siblings navigate myriad of wartime woes

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/11/2024 (380 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

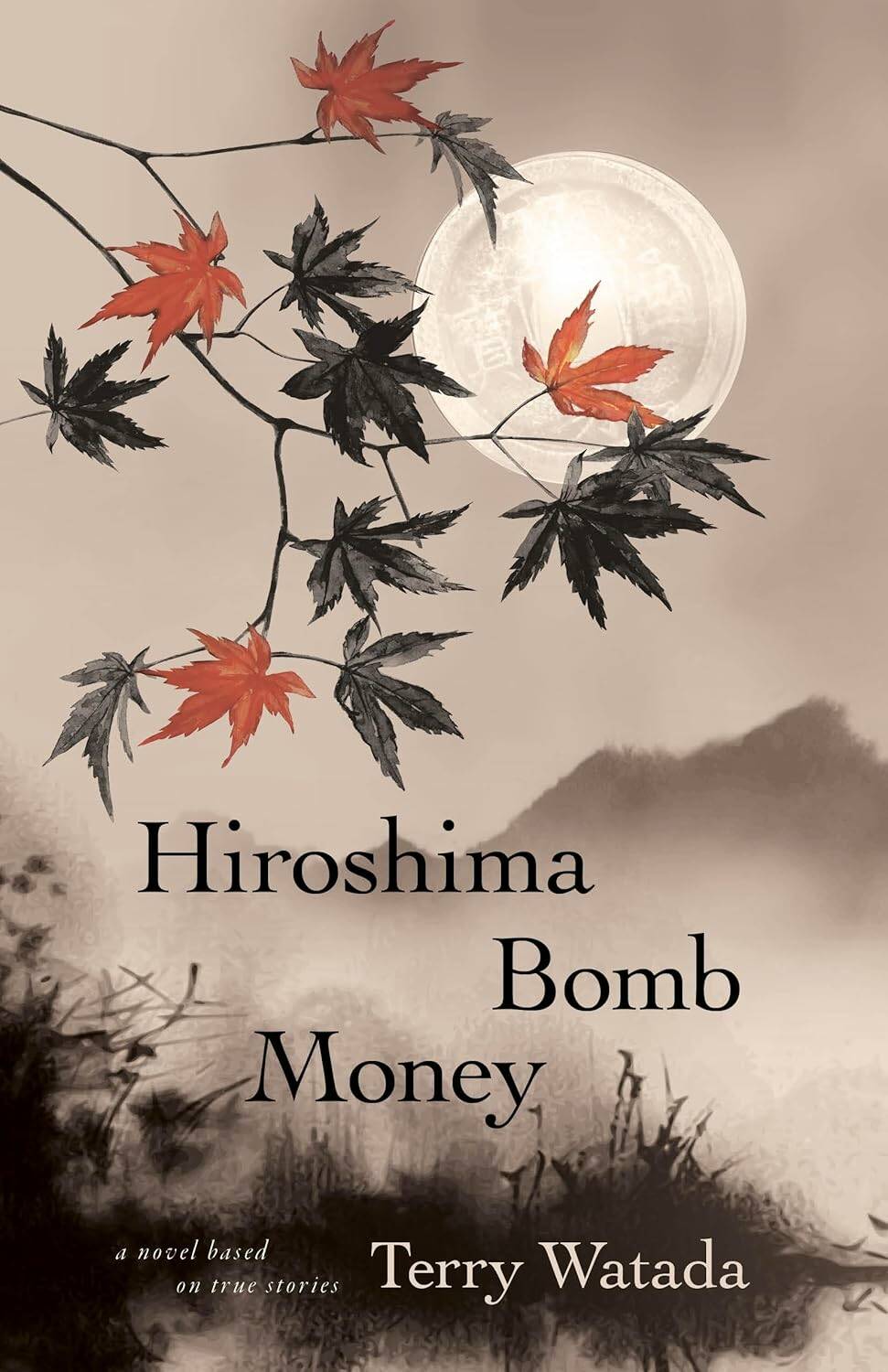

A self-inflicted tragedy: that was Japan’s experience in the Second World War. When the U.S. finally dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, the extended family of Toronto author Terry Watada’s wife lost many members and she inherited a chunk of melted-together coins (the titular Hiroshima bomb money) buried in a family compound just outside the city.

On the traces of family stories, Watada builds a fiction that follows the prewar and wartime experience of three Akamatsu siblings from Hiroshima — Hideki, who fights and witnesses Japanese atrocities in China; Chisato, who emigrates just before the war to marry a Japanese-Canadian; and Chiemi, who stays home.

Some actual governmental plans, such as the “Grand Suicide of the One Hundred Million” — when Japanese women and elderly people trained to fight with bamboo spears against the expected invasion of the American army — now seem blackly comic in retrospect.

Hiroshima Bomb Money

Watada’s depiction of the soldier Hideki as a rabid supporter of the Japanese emperor and of the war isn’t wholly convincing. Hideki’s words, though understandably nationalistic, sound like they were re-phrased from Japanese Second World War propaganda material: “China! That’s where the Emperor needs us. Glory is coming!” Once Hideki experiences relentless bullying in boot camp, he converts against the war, a shift more plausible than his early jingoism.

Later on, Chiemi and her mother memorialize Hideki as a warrior who served to bring peace, but it’s not clear whether Watada intends their words to be taken seriously or ironically.

Most completely developed is Chisato, emigrant to Canada. After a humiliating immigration process, she meets her arranged husband, Kiyoshi Kimura, who turns out to be handsome and, at first, incredibly sensitive to her needs. Somewhat assimilated, he is president of a Japanese Christian church. The church is quite welcoming to Chisato, but Watada shows how its kindly Canadian Rev. James exerts a subtle but relentless pressure on her to become Christian.

Kiyoshi, meanwhile, flips from ideal husband into caricature, revealing himself as an alcoholic who frequents prostitutes and is a brute to his wife. In Watada’s melodramatic turn, Kiyoshi asks God’s forgiveness for his alcoholism, yet continues to rage against Chisato. More convincingly, Watada later shows Chisato’s difficult road when her husband’s wealth no longer insulates her from Canadian anger against the Japanese.

A spiritual undercurrent runs through Hiroshima Bomb Money, least credible in the several mysterious appearances of Otousan’s (the father’s) ghost after his death, but far more effective in fragments of Buddhist wisdom, often at the heads of chapters. Chiemi’s Buddhist understanding — “Life is dukka” (suffering) — pervades the novel and, under mini-headings, the “Eightfold Path” (Right View, Right Resolve, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness and Right Concentration) comments on the action in complex ways.

The Buddha’s “Right Speech” aligns with Chiemi giving hospital patients words of comfort, but then patients and staff recite a loyalty pledge, swearing to help “destroy America and England” — a speech that circumvents Buddhist ideals.

“Right Livelihood” has Chiemi caring for injured soldiers; yet with her husband stationed in Hong Kong, she grows closer to the married Captain Inouye, until, under “Right Effort,” she commits adultery. It’s difficult to wholly fault her for reaching for joy as American bombing increases.

Under “Right Concentration,” the atomic bomb drops. This initially makes the teaching feel utterly ironic, but Chiemi’s concentrated actions after the bombing suggest that Watada ultimately strives not for irony, but for hope.

Reinhold Kramer is a Brandon University English professor. With Tom Mitchell, he is presently completing a book about the 1945 Gouzenko Affair.