Making her mark

Life of lesser-known women’s rights pioneer in Manitoba chronicled in new account

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/12/2024 (292 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Manitobans with an interest in history are proud that our province was the first in Canada to grant women the vote, but if asked who led the women’s suffrage campaign here, most would say Nellie McClung. A minority might say it was a team effort. Few would name Lillian Beynon Thomas.

Law professor Robert Hawkins became interested in Thomas because of her determined efforts to have a dower act passed in Manitoba. After devoting several years to the dower campaign, Thomas realized it would never happen without women’s suffrage. So in 1913, she organized the Political Equality League to lead the fight.

Born in 1874, Thomas came from a relatively poor family homesteading near Hartney. After finishing high school, she taught in rural schools off and on for 13 years, saving enough money to further her education; in 1905, when only 11 per cent of university grads were women, Thomas graduated from Brandon University. The following year, having had enough of teaching, she landed a job with the Manitoba Free Press.

Free Press files

Clockwise, from top left: Lillian Beynon Thomas, Winona Dixon, Dr. Mary Crawford and Amelia Burritt presented the final petition for women’s suffrage on Dec. 23, 1915 to the Manitoba Legislature. The amendment to the Manitoba Elections Act allowing women to vote, the first such legislation in Canada, was passed on Jan. 28, 1916.

For the next 11 years, Thomas edited the women’s page of a widely distributed weekly, The Prairie Farmer, and for five years wrote a daily column in the Free Press as well.

Thomas already knew a great deal about the hard lives of Prairie women, and she learned even more from letters to the women’s page. As well as fighting for a dower act, she helped establish Women’s Homemaker Clubs in Saskatchewan and became a mentor to Violet McNaughton, who led the suffrage fight there.

In Manitoba she was involved in establishing a women’s branch of the Manitoba Grain Growers’ Association and supported other groups such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union which, along with the Icelandic Women’s Suffrage Association, had petitioned for women’s suffrage since the 1890s. She was a friend of J.S. Woodsworth and MLA Fred Dixon, both pacifists, and she was involved in the All People’s Mission’s educational work.

Hawkins has determinedly scoured archives for details of Thomas’s life before she founded the Political Equality League in 1913, but, as to her part in achieving the vote, there’s little new information here. Catherine Cleverdon, author of The Woman’s Suffrage Movement in Canada, questioned many of the participants, including Thomas, her sister, Francis Beynon and Nellie McClung.

Still, Hawkins makes a good case that Thomas’s role in achieving the vote here was pivotal. In addition to playing a key role in organizing speakers, petitions and pamphlets, the staging of A Women’s Parliament at the Walker Theatre in 1914 was her idea.

In wake of that sold-out performance, which featured McClung and Thomas improvising as premier and leader of the opposition, the Manitoba Liberals finally endorsed women’s suffrage. Then, in 1915, Conservative premier Rodmond Roblin was forced to resign over corruption charges, and the Liberals took over.

But once again there was a challenge, and this one was clearly solved by Thomas. The original Liberal suffrage bill did not include women’s eligibility to run for office. Learning of this, Thomas threatened that the new government would be denounced at an imminent Manitoba Grain Growers’ convention. The Liberal premier, Tobias Norris, gave in, refusing to speak to Thomas for years.

A few years later, Thomas succeeded in having a dower act passed in Manitoba. It was the last act of her political activism; meanwhile McClung, her life-long friend, went on to serve in the Alberta legislature and to support the Person’s Case which made women eligible for the senate.

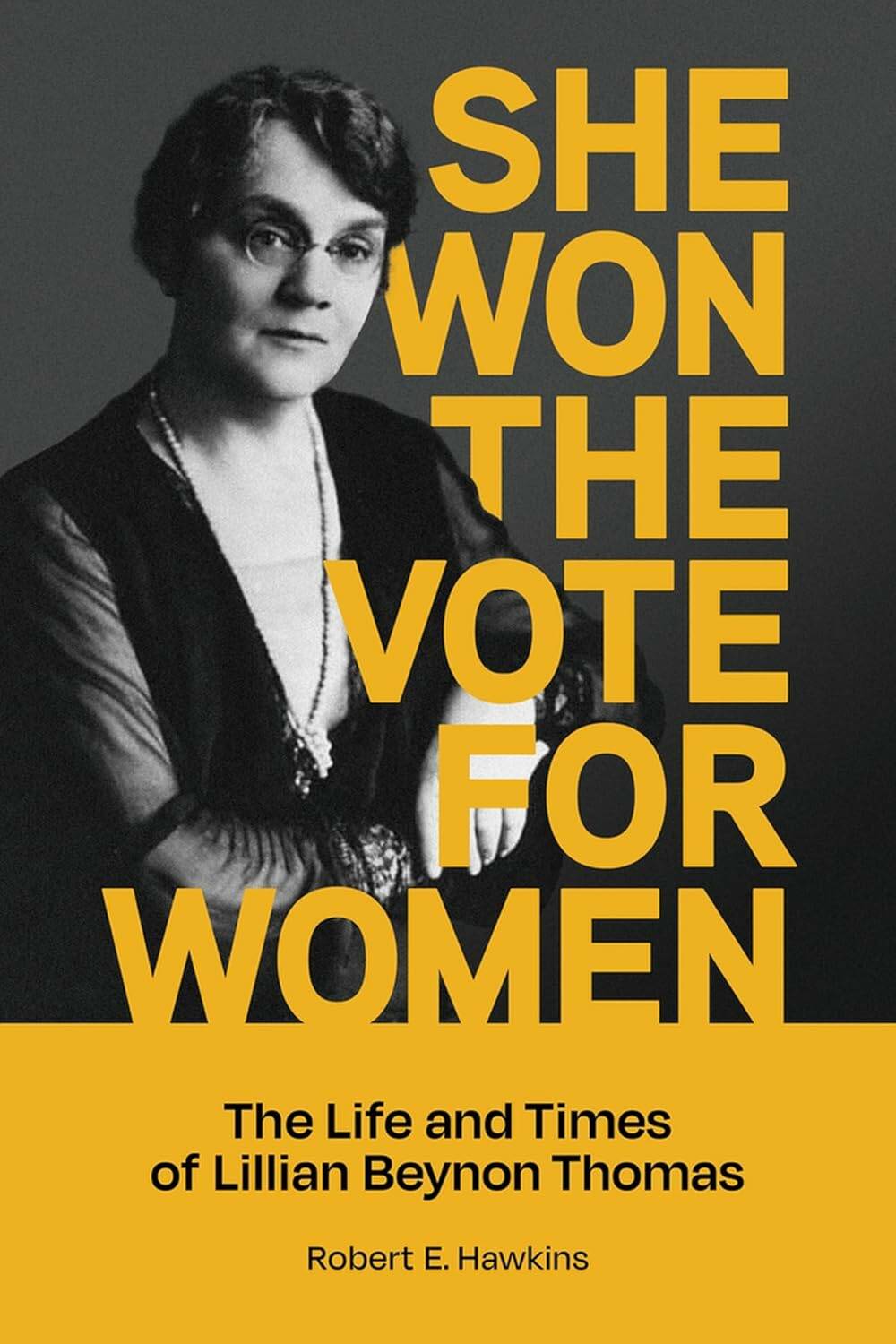

She Won the Vote for Women

In 1917 the Free Press fired Beynon’s husband, Alfred Vernon Thomas, for his pacifism, and the couple moved to New York. When they returned in the 1920s, Lillian devoted her time to writing short stories and plays, quite successfully, but from what we know she never dipped her foot in the political arena again.

Readers may leave this book wanting to know less about the plots of her short stories and more about her personality and values, such as the origin of her own pacifism; however, it is clear Hawkins has probed all available sources.

Beynon’s death in 1961 was not mentioned in the Winnipeg Free Press, but an article in the Winnipeg Tribune, where her husband worked after his stint with the New York Times, was headlined “She Won the Vote for Women.”

Faith Johnston wrote a biography of Dorise Nielsen, the first woman from Western Canada to serve in Parliament.