Danish-set novel doth frustrate too much

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/03/2025 (209 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The world would be a dull place indeed if every work of art aimed for the broadest possible audience.

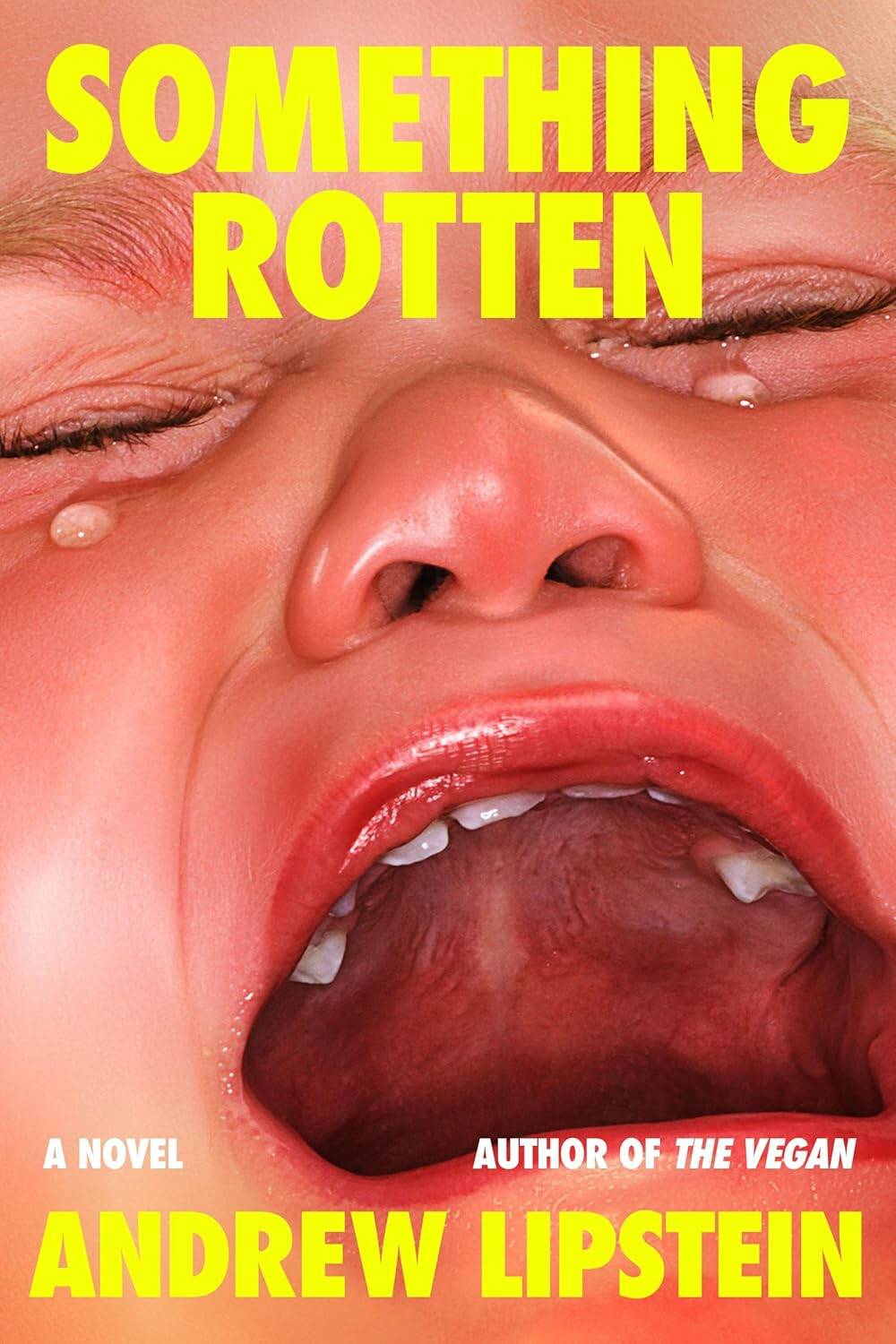

But American writer Andrew Lipstein’s new novel, Something Rotten, arguably goes overboard in the opposite direction.

It is just too specific — about too narrow a demographic of yuppie, liberal, self-critical, internationalist “creative class” members — for its own good.

Something Rotten

This is a comedy of manners aiming for psychological complexity, a-la Jonathan Franzen or Jennifer Egan. It follows two main characters, Reuben and Cecilie, a married pair of journalists in their mid-30s, to Copenhagen, where they attempt to reset their relationship and their careers.

Something Rotten is Lipstein’s third novel in just over three years. He tells the story in chapters alternating between Reuben and Cecilie’s point of view.

They had been in New York City, where Cecilie, a transplanted Dane, was a reporter with the New York Times.

Reuben, an American, had been a successful National Public Radio host. But he has lost his job, “cancelled” after he made an embarrassing mistake during a Zoom meeting involving a sex act (with Cecilie).

He is now a house-husband, caring for their baby son, nursing his wounded pride, worrying about his reputation and obsessing about his fragile masculinity.

In Copenhagen for the summer, living with Cecilie’s widowed mother, Reuben and Cecilie fall in with her old journalism school friends, a collection of self-assured Danes out of a Thomas Vinterberg movie.

Reuben hangs with the guys, who enjoy such male pastimes as drinking and smoking. (Nicotine is definitely Lipstein’s drug of choice.)

One particular male in group, Mikkel, the novel’s bad guy, wields Svengali-like control over poor Rueben.

To make matters worse, Cecilie gets together with old her boyfriend, who may or may not be dying of a rare brain disease.

Throw into the mix a subplot wherein Mikkel has broken a major story about a far-right Danish politician, and another in which Reuben is searching for his birth father.

A lot is going on, but these plot points do not coalesce into a satisfying whole.

The novel’s most interesting parts are sociological. Throughout the book, Lipstein contrasts the harshness of U.S. individualism with Danish social democracy. “Danes were in such accord,” Reuben observes, “that they hardly needed traffic signs.”

A couple of ill-advised stylistic quirks make the novel hard to read. Lipstein peppers the text with Danish words and phrases, which he then translates into English.

More annoying is his decision to put the scant dialogue, both English and Danish, in italics rather than inside traditional quote marks. This has the unintended effect of every spoken word feeling emphasized.

Other choices seem odd, too. Why does Lipstein give his male protagonist a traditionally Jewish first name when neither he nor the character is Jewish?

And why is the action set in 2026? (There is one reference to this, on page 3). Working on the manuscript pre- November 2024, Lipstein could not have predicted the results of the U.S. presidential election. But the absence of Trump makes a politically conscious novel seem beside the point.

You don’t have to be an English major to realize that Lipstein’s title alludes to Shakespeare’s Hamlet. But the parallels between the two works lie well below the surface.

There may be something rotten in the state of Denmark, but Lipstein’s exasperating novel is not going to bring it into daylight.

Morley Walker is a retired Free Press writer and editor.