Banks for the memories

In dystopian debut novel, democracy’s decline and death rings all too familiar

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

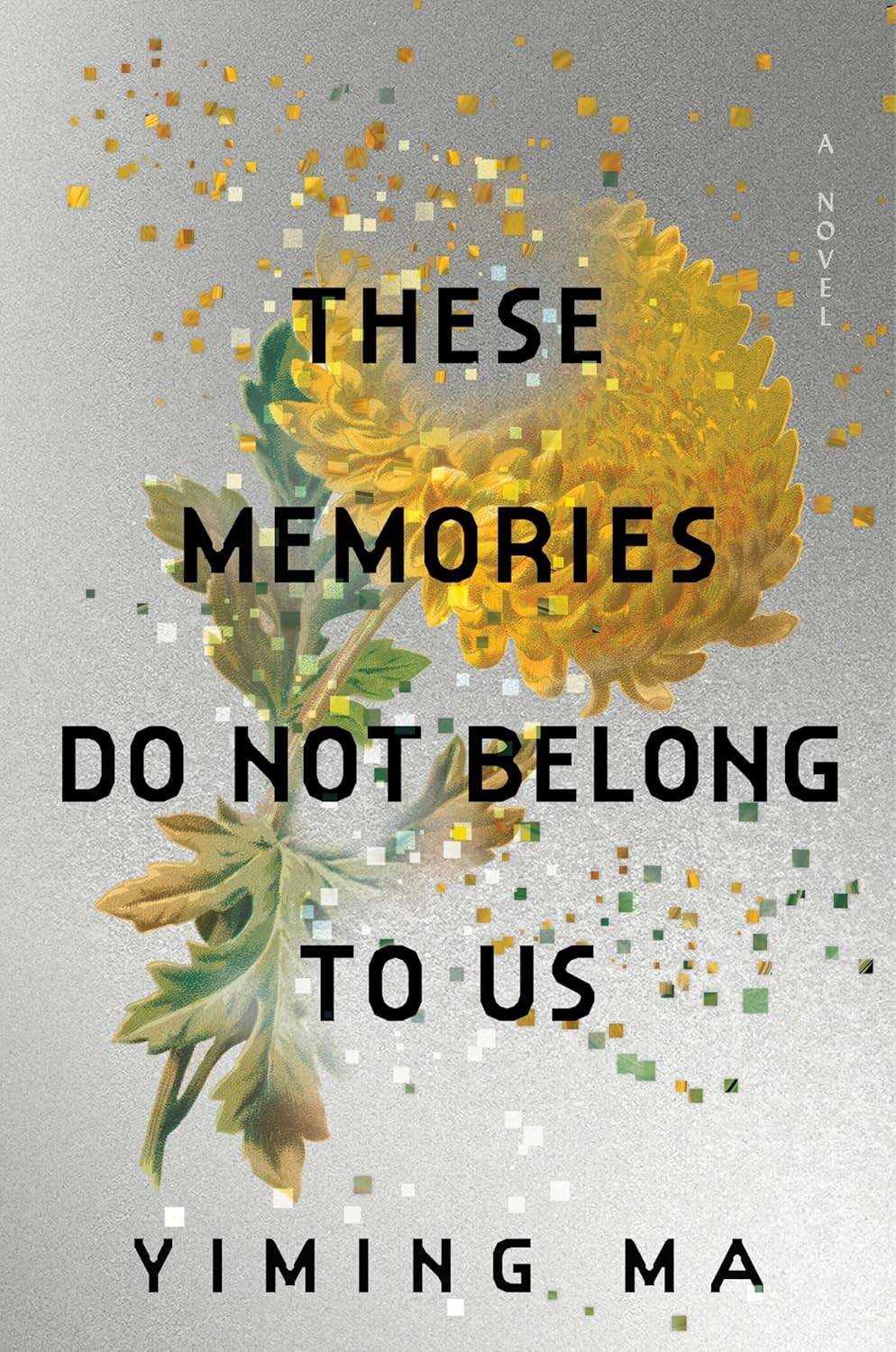

Toronto-based author Yiming Ma’s debut work straddles the line between novel and short-story collection, as he knits the tales of a dozen or more viewpoint characters into one overarching narrative in which a future People’s Republic of China has taken over the entire world.

Threaded throughout that story of conquest is the sci-fi concept of a brain implant, Mindbank, that allows individuals to upload and download memories. The basic conceit Ma employs here is that every story in this book is in fact a banned memory file, with the framing device of an unknown custodian exploring each story while he waits for the government to notice their illicit nature and whisk him away to a re-education camp.

These files include the memory of a would-be author trying to write the last great novel before “Memory Epics” completely replace writing as an art form, but getting caught up in an escaped plague from a nearby biotech lab. And the layered memories of one Japanese man’s experiences in a fiery wartime Holocaust, whose experiences alternate with the Chinese memory artisans working a century later to alter and rework the story to get it past government censors for public release.

Emma Norman photo

Yiming Ma’s powerful debut contemplates how social divisions serve the purpose of the oppressing government.

Some stories span the period “before the war,” anywhere from Mao Zedong’s 1960s Cultural Revolution to the present day. Others are from the war period itself and others still take place decades or centuries after the planet-spanning iron rule of the Qin Empire is firmly in place. The viewpoint characters are all Chinese in origin, but range from mainlanders to immigrant families that have become more culturally American.

Race and class are important throughout this work. Is one connected to the Party or not? Is one Chinese-born or foreign-born? Is one yellow, black, brown or white? While Japanese, white Americans, and Black Americans never serve as viewpoint characters, their stories are key to understanding the full picture of this future oppressive society. Ma is clearly always thinking about how social division serves the purposes of the oppressing government, even though he rarely states it explicitly.

One of the most prescient tales centres on the Gaokao, China’s real-life national university entrance exam. This single standardized test can have a profound effect on a young person’s future, usually seeing them study obsessively for years. However, when future technology allows knowledge to be acquired through a simple memory download, the form of the Gaokao changes to a horrific test of grit: examinees are transported to a virtual desert and are tasked to trek for days or weeks until the simulated thirst, pain and injury finally break them. Tellingly, the test is presented as meritocratic, but the reader finds out it is blatantly rigged against test-takers of certain backgrounds, with the protagonist discovering the test has removed one of his legs prior to the start of the race.

The most prominent theme, reinforced by the framing story, is the Orwellian idea of controlling the flow of information to control the populace. Mindbanks, initially an assistive technology, grow over the decades to replace all mass-market entertainment and all social media, and ultimately subsume the social credit system as human thoughts and memories become literally searchable and citizens’ subversive thoughts are inevitably exposed to the Party.

George Orwell’s 1984 showed, through the experiences of one character, how all the different pieces of a government machine could squeeze out any hope of individual liberty or resistance. These Memories Do Not Belong to Us shows those elements of oppression being assembled, bit by bit, across decades and centuries, squeezing the noose tighter, pushing the tendrils of surveillance into ever smaller recesses of individual lives.

The content of this book seems timely, but it’s actually timeless. At any point in the last decade readers would have a touchpoint — today it’s ICE rounding people up into American concentration camps, before that Russia’s blatant state media spin on its invasion of Ukraine, or the Chinese government’s efforts to smother the Hong Kong protests, or still yet the fizzling out of the Arab Spring. When is autocracy not on the rise somewhere or other?

These Memories Do Not Belong to Us

Yiming Ma’s deft, layered commentary on how democracy dies is unfortunately only too relevant. This may be one of the most important books published this year.

Joel Boyce is a Winnipeg writer and educator.