Bent but not broken

Thomas’ powerful prose offers window into struggles with trauma, fatherhood and more

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

‘My story is of broken men, each of whom, at one time, had to transform their legacy and in doing so transform themselves and the inheritance of those to come.”

So begins Michael Thomas in the opening lines of The Broken King, his powerful memoir that breaks and heals hearts simultaneously.

It’s a blunt but beautiful treatise on fatherhood, addiction, intergenerational trauma, mental illness, police brutality and being Black in America.

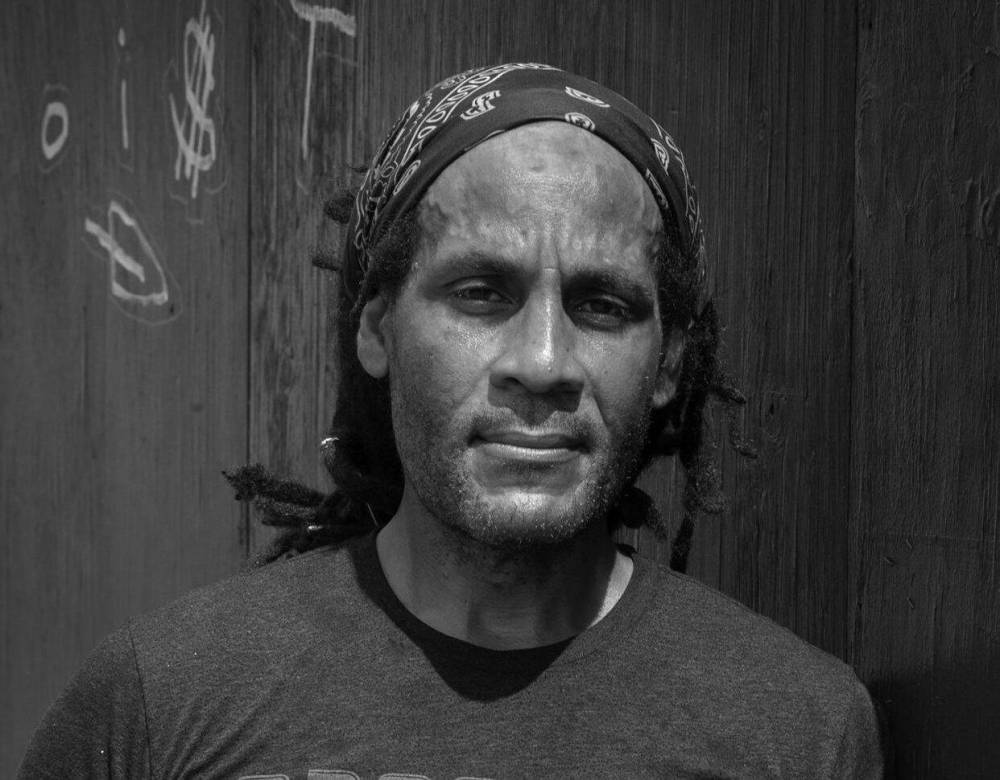

Ben Russell photo

Michael Thomas burst onto the literary scene in 2007 with Man Gone Down, a searing novel about an African-American man trying to reunite with his white wife and their three children.

Thomas boasts an impressive background, with roles in theatre, hospitality and writing, and now as a professor at New York’s Hunter College.

He burst onto the literary scene in 2007 with Man Gone Down, a searing novel about an African-American man trying to reunite with his white wife and their three children.

Retroactively described by Thomas as a “suicide note,” it’s a semi-autobiographical story about the hopelessness of trying to achieve the American dream as a Black man.

In The Broken King, Thomas goes further, telling his history through five interlocking narratives exploring his complex relationships with himself and four of the men around him.

Thomas’s brother David moves in and out of Thomas’s life, caught up in money-making schemes that often leave Thomas and his wife to bail him out.

Thomas’s father, a voracious reader, philosopher and Boston Red Sox fan, endows Thomas with a love of learning and sports, yet abandons Thomas both emotionally and, later, physically.

Determined to do better by his children than his own father, Thomas dedicates as much time as he can to them, but finds himself struggling to meet their needs when his own childhood scars are unhealed.

“I often feel that because I have not completely freed myself from what my father bequeathed me, I will always endanger my son,” Thomas writes of his relationship with his oldest child.

Thomas links the segments with his overarching story of self-doubt, artistic development and struggles with mental health.

After he finally achieves success with the publication of Man Gone Down, the pressure and undiagnosed depression overwhelm him, leading to what he terms his “madness.”

This is no summer beach read; Thomas spares readers from none of the pain he has experienced.

He bluntly states the complexities and often brutalities of living as a racial minority, especially one married to a white woman of a well-meaning but often misfiring family.

Thomas notes that his white family members always gave his oldest son “politically correct toys, games, and books” that they thought “melanin appropriate,” while being unequipped to actually understand racial identity: “(T)he white people who wanted to claim him as their own hadn’t any means or methods to protect him in the world in which they were trying to indoctrinate him,” he recalls.

The Broken King

While the narrative focuses on Thomas’s relationships with key men in his life, the women in his life, especially his wife and sister, appear as powerful sources of strength and support.

Even his volatile mother inspires him, with Thomas recognizing that while her own unresolved trauma held her back as a mother, “she still fed us and loved us with as much of herself as she could offer.”

The most brutal scenes — assaults by strangers and, frequently, police and security guards and the like — take place mostly off the page, and Thomas keeps the focus on the effect they had on him.

Readers may be reminded of the work of pivotal African-American author James Baldwin, who explored many of the same topics (and whom Thomas references frequently as an inspiration).

The Broken King richly pulls references from writers such as Shakespeare, Mark Twain, W.E.B. DuBois, Charles Dickens, W.H. Auden, Frederick Douglass and T.S. Eliot, whose poem Little Gidding gives Thomas his book’s title.

Meanwhile, Thomas’s command of language brings to mind the work of American novelist Vladimir Nabokov — someone else Thomas cites as a writing influence.

Like Nabokov’s controversial 1955 novel Lolita, Thomas’s gorgeous, lush prose overlays a dark subject.

But despite that darkness, Thomas infuses his memoir with a powerful, beautiful hope, noting, “I’ve come to believe that the effort to make something beautiful — and only the most sincere effort, unaffected by potential outcome, material gain or loss — is the only thing that can prevent us from falling into darkness.”

Kathryne Cardwell is a Winnipeg writer.