American history of violence permeates popular music

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

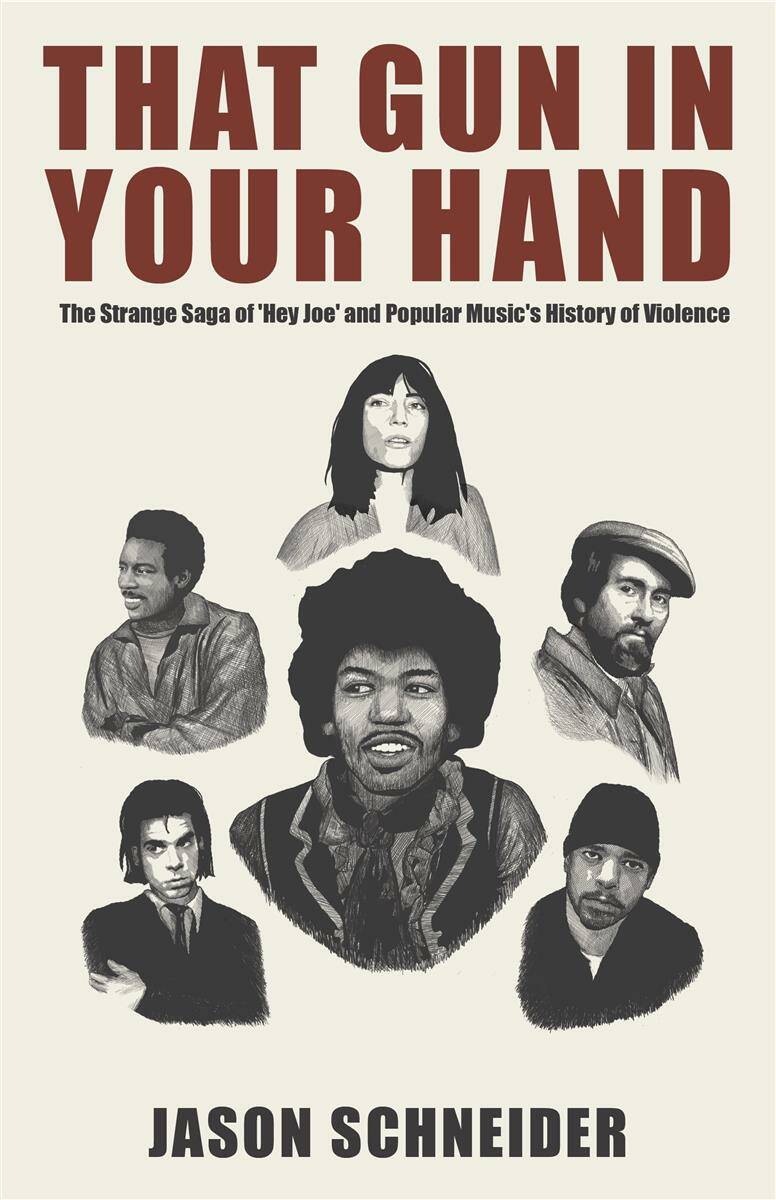

The title of Jason Schneider’s new book is lifted from a lyric in the song Hey Joe, to wit: “Hey Joe / where you going with that gun in your hand?” It’s a song with a conflicted legacy of authorship and motley history of renditions.

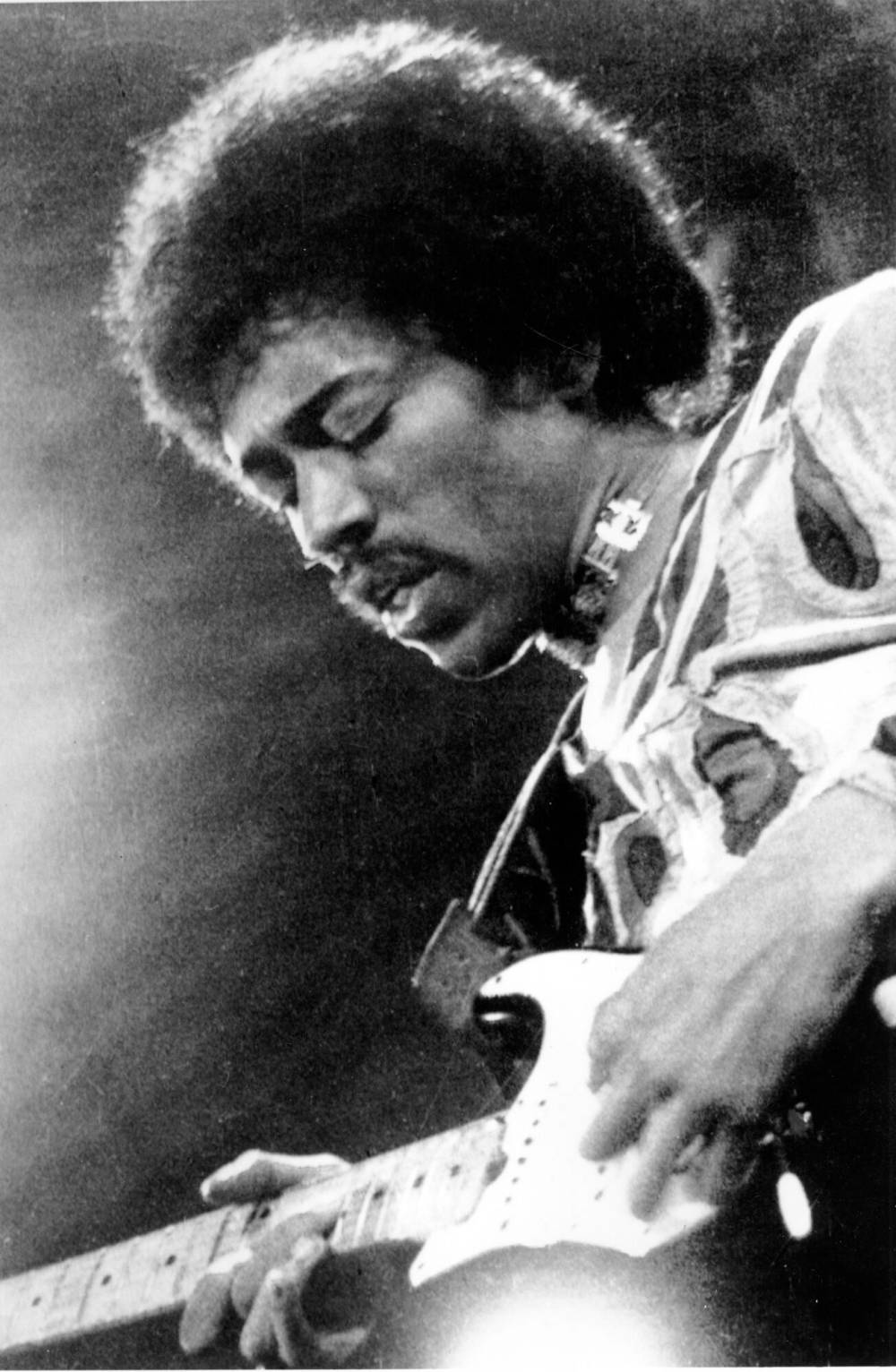

The best-known version is probably the bluesy amplified juggernaut loosed on the world in 1968 by guitar god Jimi Hendrix.

But despite the book’s title and yet more explicit subtitle, this isn’t just the story of a song.

Associated Press files

Jimi Hendrix’s version of Hey Joe is the best-known of the various renditions.

The narrative thread woven around the classic song is a pretext for Schneider’s examination of “20th century popular music’s unholy marriage with violence.” By popular music, he means folk, blues and mostly rock ‘n’ roll.

The result is a highly original take on music as a guide to the heart and soul of America’s pathological embrace of guns and violence.

Schneider is a Canuck based in Kitchener, Ont. He’s penned five prior books, some on music, including Whispering Pines: the Northern Roots of American Music from Hank Snow to The Band (2009).

Canadians take America for granted, having long assumed our neighbour is a benign nation. But its popular music is chock full of warnings it’s not benign and never has been, Schneider argues.

The United States has the world’s highest rate of civilian gun ownership. There’s an estimated 393 million privately owned firearms in the U.S., according to the Geneva-based Small Arms Survey (SAS) project, which translates to roughly 120.5 firearms per 100 residents (children included).

The music, Schneider believes, articulates the inherent violence of American culture. That music’s images, while primal and aesthetically powerful, are also sad and repugnant.

Most of the book’s 15 chapters are organized around mini bios of individual rock, blues or soul artists. Billy Roberts, composer of Hey Joe, gets the opening chapter and the luminaries that follow include David Crosby, Roy Buchanan, Wilson Pickett, Patti Smith, Dino Valenti and Hendrix.

The chapters are, at base, critical essays deftly centred around artists whose music is thematically steeped in violence, usually criminal violence.

There’s a sidebar legal story to the song’s history.

Everybody and his dog did covers of Roberts’ creation — The Byrds, The Leaves, Tim Rose, Cher, Valenti, Pickett, Deep Purple, Robert Plant and, of course, Jimi Hendrix.

That Gun in Your Hand

Many falsely claimed copyright to themselves, mistakenly credited it to someone other than Roberts or simply cited the song as being without ownership provenance and therefore in the “public domain.”

But in a prescient move, in January 1962 Roberts registered copyright of the song with the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Armed with proof of copyright, Roberts was subsequently able to verify his proprietary rights and collect at least some royalties.

This book isn’t just music criticism. Schneider draws insightful connections between the music he clearly loves and just about anything else he deems significant in American politics and culture.

His frame of reference is so extensive it sometimes morphs into cultural history.

At first blush, it sounds silly to build a book around a single song. But the genius of this book is that it both is, and isn’t, about a single song.

It’s about how popular music, decade after decade, darkly reflects broad swaths of American culture.

Douglas J. Johnston is a Winnipeg lawyer and writer.