Journalist’s darkly comedic Gaza novel fizzles

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

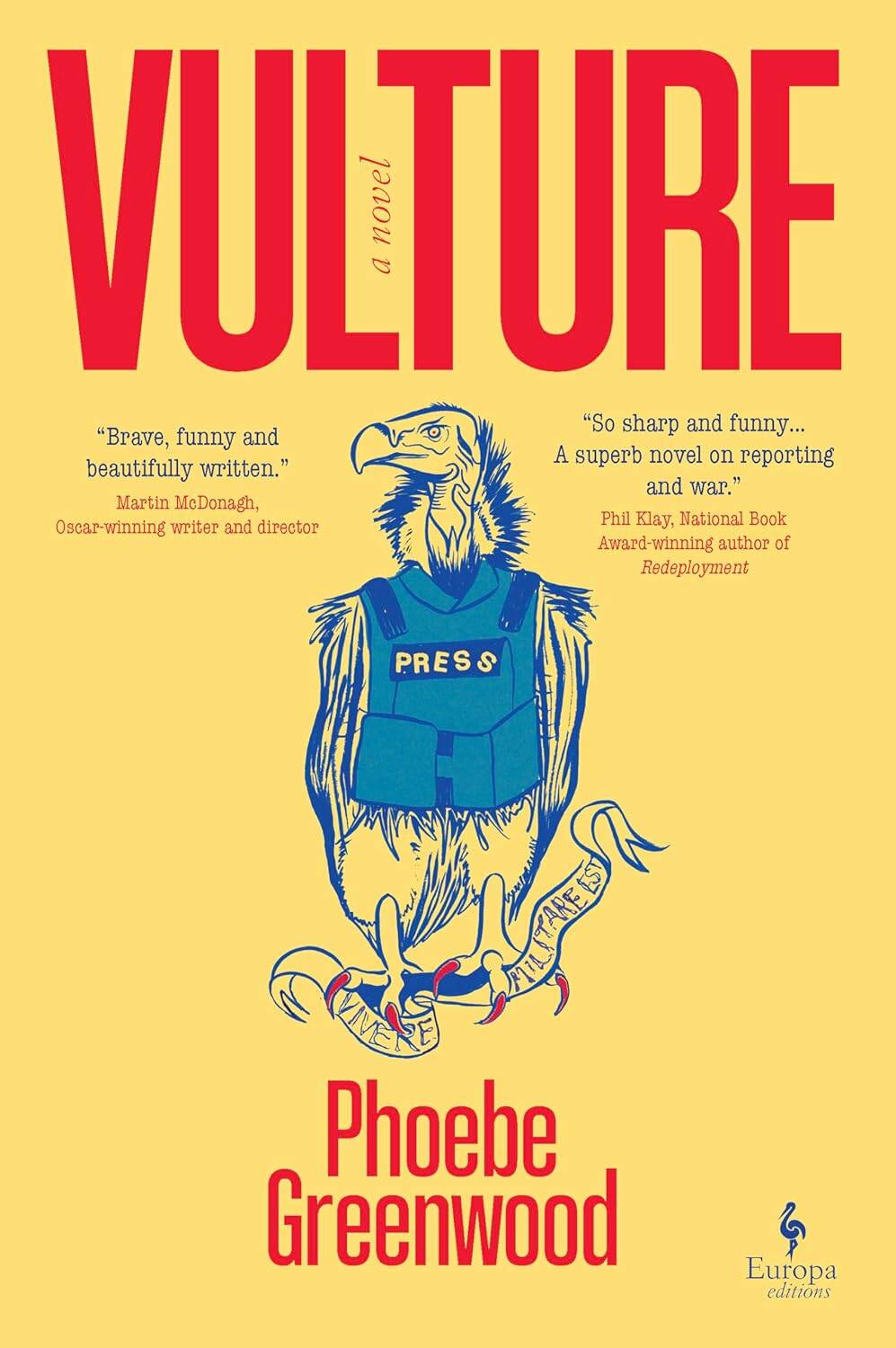

Phoebe Greenwood’s novel Vulture takes readers back over a decade to life in Gaza, drawing on her background as the Jerusalem-based stringer covering the Middle East for the Guardian, Daily Telegraph and Sunday Times.

Opening in 2012, the central character is a young journalist, Sara, trying to launch herself as a star correspondent through her coverage in the area, from the foreign correspondents’ base at the Beach Hotel.

The hotel opened in the spring of 2000; Mo, the hotel’s owner, describes the time as the “glory days of (Yasser) Arafat.” Within a month, the second Intifada began, Arafat died, the Fatah political party ran away to the West Bank and Gaza was left with Hamas.

Vulture

But, Sara notes, the Beach Hotel is still nice and American network crews like nice hotels. They like airy sea fronting suites and restaurants with uniformed waiters where they can eat french fries and safely watch the war raging in the streets and skies outside on big TV screens.

The writing style here falls far short of the publishers’ hype on the cover, but it is nonetheless a a good yeoman’s portrait of Gaza, a perpetually troubled region. Like other foreign correspondents, Sara relies on a fixer — a local resident who serves as a translator and helps her find stories.

Set 12 years ago, in Vulture Sara notes that the Gaza she knew no longer exists. Reporting was often focused on Hamas as the bad guy, and then, as now, Israel was using Hamas as an excuse to slaughter Palestinians.

When a building collapses after a bombing, Sara, through her fixer Nasser, talks to an old man who lived there. His whole family was killed, including six children, but “it’s God’s will.” He says Hamas was not there — that his son was traffic police, not Hamas.

Sara is anxious to get out and start talking to the people in charge of the war and displays the callous attitude of many foreign correspondents.

“We’d had four days of Gaza being on the front page of the Tribune but there were only so many bombed families that could sustain that sort of interest and old man Al Muzaner just wasn’t going to cut it. Unless there was a full ground invasion or Israel started dropping their chemical weapons, it was all getting a bit samey,” Greenwood writes.

The solution, Sara decides, is to get into the tunnels and talk to members of Hamas. Her fixer disagrees.

“‘When the one thing Hamas does really well is terrify people, you want me to get these terrified people to tell you about their secret tunnels?” Nasser asks, continuing, “Do you know, Sara, how many people would be killed if we ran a story like that? How Israel would use it to justify bombing any mosque, any home, any school in Gaza?’”

Sara refuses to see the danger, or care about the threat to the local residents. “What did he think the Tribune was paying him $400 a day for?”

Back at the hotel, Sara reveals a callous disregard for the consequences of her stories. “I wasn’t getting anywhere with this war. Him and his prissy, sanctimonious, judgy blocking of my efforts to report anything interesting.”

Sara notes the cynicism of the international media.

“Of course, international outlets couldn’t let Palestinians actually report the news. Even if they were fluent in English, it wouldn’t look right because of balance and impartiality. But they were essential for setting up whatever story a foreign correspondent needed.”

Sara and other foreign correspondents seem to have plenty of time for recklessly casual sex which results in Sara getting a case of herpes. When she gets home to London, her yellow eyes are explained away as being the result of hepatitis. There seems little point to these sex scenes other than to meet some arbitrary quota of so-much-sex per so many thousand words. They do nothing to advance the story.

Similarly, there seems little point to flashbacks to her childhood, when she adored her now-dead father and hated her mother. This only serves to pad out the story.

For a sample of Greenwood’s better writing, search out her news stories online.

Gordon Arnold is a Winnipeg writer.