Imbalance of power

Thorough chronicle of shah’s reign comes at a potentially inopportune time

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Scott Anderson was an 18-year-old political aide killing time on the White House lawn on Nov. 17, 1977, when the Iranian Revolution was launched there — by thousands of students who had turned up to witness the arrival of the Iranian dictator, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, for a meeting with U.S. President Jimmy Carter.

Of course no one recognized the import of the live broadcast of the “massive street brawl” that broke out between pro- and anti-shah forces — not Iranians watching back home nor Anderson, who was knocked to the ground by a plank-wielding protester.

But, as might be expected, the incident had an indelible impact on Anderson who, after a career as a foreign correspondent and award-winning author, has written what might be the definitive history of what happened in the 14 months after that fateful November day, ending with the collapse of the shah’s regime and his flight from the country he had misruled for 38 years.

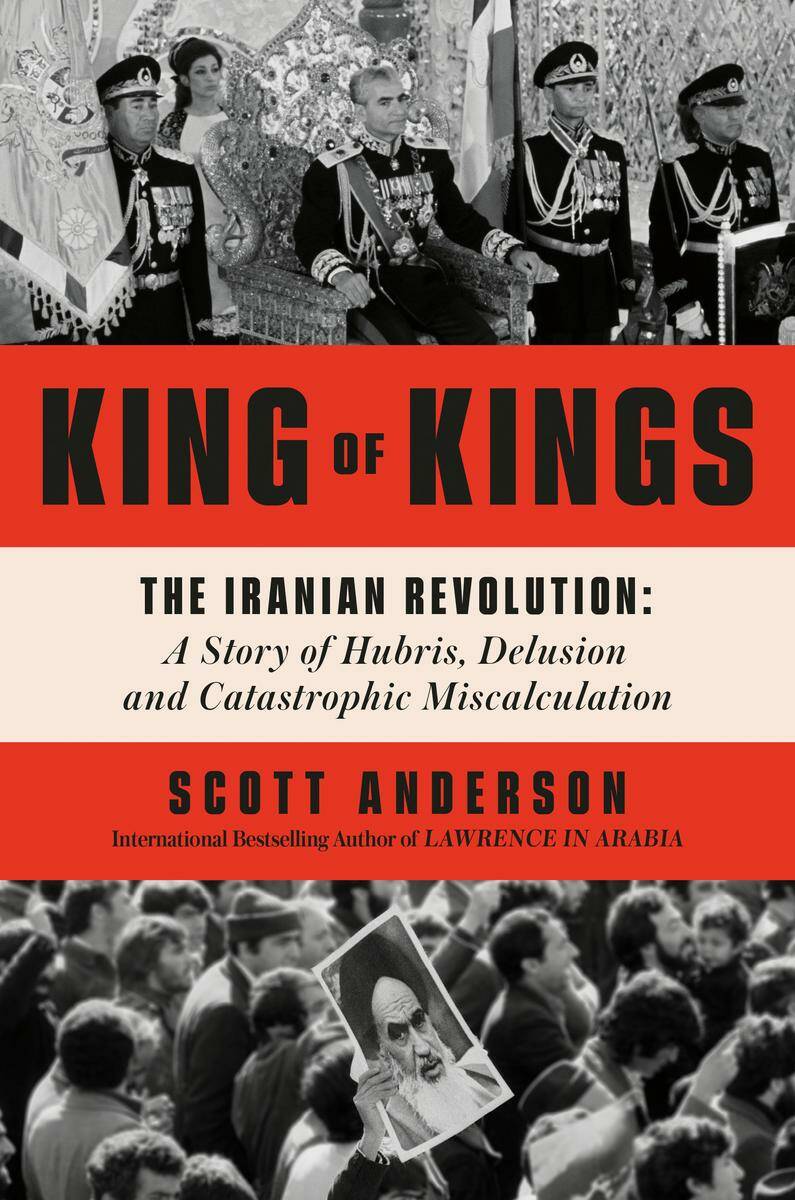

PAHLAVI.ORG PHOTO

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, seen here in an official portrait, reigned as shahanshah of Iran from 1941 until 1979.

As good and thorough as King of Kings most certainly is, however, events have perhaps rendered it the wrong book at the right time or, conversely, the right book at the wrong time.

The reason? The Islamic theocracy that usurped the shah and has ruled Iran with an iron fist ever since suddenly looks a bit vulnerable, as did the shah that long-ago day in Washington.

The Islamic Republic’s “friends” in the Middle East are gone — the Assad regime in Syria collapsed last year and the Hamas militia in Gaza has been decimated after starting a war with Israel, which decapitated the leadership of Hezbollah, Iran’s proxy army in Lebanon.

Meanwhile, in surprise attacks, Israel has wiped out much of the Iranian air force and, with American assistance, has seriously disrupted Iran’s feared nuclear program.

In other words, right now what the world wants to know is what might happen in Iran next week — not what happened in Iran 48 years ago.

Which is unfortunate because Anderson has written a great true story, the tragedy that the “King of Kings, Light Of The Aryans, Shadow of God on Earth”— otherwise known as Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi — forged for himself.

“He was a soft man masquerading as a hard one,” Anderson concludes. “He was a waffler, an equivocator, even something of a coward, in that, when dirty work was to be done, he looked for others to carry it out. In addition, he made the fatal mistake of believing his own propaganda.”

The shah, however, wasn’t the only naive believer. If anything, Anderson is more scornful of the naiveté of American intelligence community that never saw the revolution coming.

It seems impossible to believe, but among the hundreds of American diplomatic personnel in Iran at the time, only one spoke Farsi. All the rest relied on local, elite, English-speaking (and handsomely paid) urban employees to describe what was going on in the country.

The U.S. government, Anderson writes, saw the shah as a reliable policeman and bulwark against Soviet expansion into the Middle East. His army, the fifth largest in world, was equipped by American arms makers, who employed hundreds of thousands of Americans.

King of Kings

Iranian oil fields lubricated the American economy.

“In sum, the shah was so profoundly important to the United States that it couldn’t conceive of life without him, and so it did not,” Anderson writes.

And even if the Americans were not suffering from jaw-dropping ineptitude, Anderson argues that it was impossible then, and now, to put a finger on what might be considered a seminal event or person that led to the revolution. Instead it was more like a steel ball bouncing around inside a pinball machine that produces a “matched number” and an unearned free game.

The taking of 52 American hostages in November 1979, for example, was not a master-stroke of strategic planning, but rather a hair-brained scheme hatched by a bunch of students hoping to find secret documents in the U.S. Embassy.

In the end, America’s fears that Iran might embrace Moscow proved to be a “historical irony” in that, writes Anderson, “from an American standpoint a Red Iran would have been far preferable to the Iran they got.”

And what they got was Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini, an Islamic extremist cleric, under whose authority 8,000 Iranians were executed in his first four years, compared to 100 in the final 10 years of the shah’s rule.

Gerald Flood is a former Free Press comment editor.