Shared world of books bind author, smuggler and wayward soul in otherworldly beauty

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

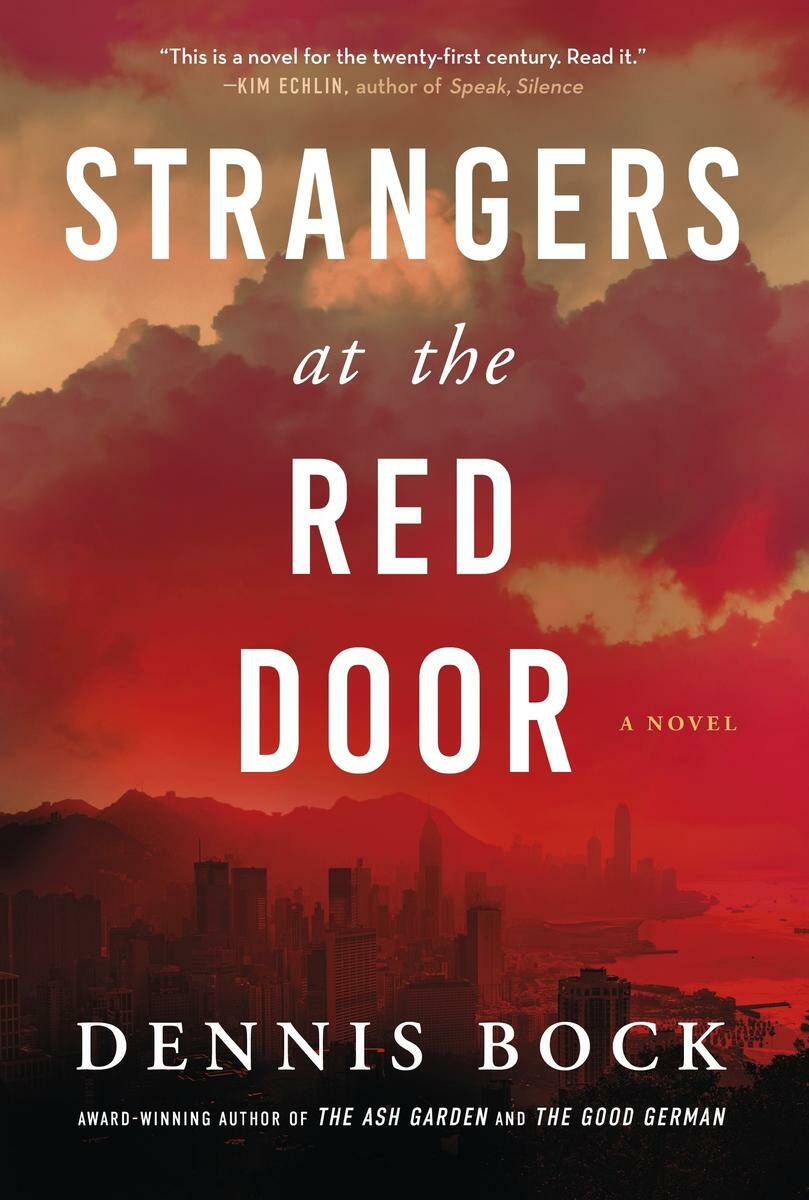

In award-winning and bestselling Toronto author Dennis Bock’s strange, affirming and lovely sixth novel, two bookish strangers, lonely and in the middle of their lives, run into each other three times — in a country of nearly one and a half billion.

Mildred Chen is a Hong Kong bookseller and publisher who smuggles forbidden books across the border into mainland China. She is driven to this mission in part by the death of her parents, who were disappeared when she was a baby during the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown.

Faron Jones is a successful Canadian ghostwriter with a dying mother and estranged sister whose artistic courage and sincerity peaked in his early 20s when he published his only novel, Strangers at the Red Door. This book isn’t only a youthful first stab. It is a generational achievement he can’t replicate.

Strangers at the Red Door

Faron is in China for two reasons: to reconcile his sister, who lives there, to his mother, and to visit a famous Iranian dissident and actress who wants him to ghostwrite her memoir.

Each time Mildred and Faron meet, a third stranger moves between them, seeking a pathway to another scale of being. This is the soul of a writer named Jiang Ming, who died 17 years ago and whose books, Remedies for Obedience and Beijing Soul Asylum, are the contraband smuggled by Mildred.

These three aren’t the only strangers brought together by the shared world-upon-world of books. If Faron took from the real world to fashion his characters when he wrote Strangers at the Red Door, those characters have kept their power and seep out to alter his midlife in ways he will only come to understand.

Considering the bizarreness of the premise and the ambiguity of the register — where travelling souls, ghosts floating out of mirrors and encounters with strange ladies scuba diving in aquariums are presented as realist — it is a continual, magnificent surprise that the book makes perfect sense at every turn. This is partially due to its careful, clear prose, and partially due to Bock’s bold commitment to his otherworldly pursuit.

One of the best examples of Bock’s register might be an eerily delightful, fairy godmother-esque old woman with inscrutable features (“as if her advanced years had graduated her to some unique realm of pure humanity”) who sells fairy drones in the train station. Of all the characters, this old drone seller seems to see everything — the living and the dead, who needs what, who is connected to whom — and uses her mechanical fairy as an instrument of grace. It’s that drawing together of disenchanted, mass-produced drones with intelligence and life that best expresses the book’s worldview — one in which the living and the non-living are nested closely together.

In his Acknowledgements, Bock says Strangers at the Red Door was inspired by a trip he made to China in 2015, the year five Hong Kong booksellers disappeared and then resurfaced in the hands of Chinese authorities.

We can accept the invitation to place this novel in the current context of growing authoritarianism and book censorship. But Bock’s story feels less reasonable than this, offering more than a liberal critique of state censorship. It is also a proud, faithful devotion to the ensoulment of books, people and even fairy drones and to the capacity of human creativity to expand reality when “suspicion and fear and self-censorship” cease to rule the heart.

Seyward Goodhand is a Winnipeg writer and instructor.