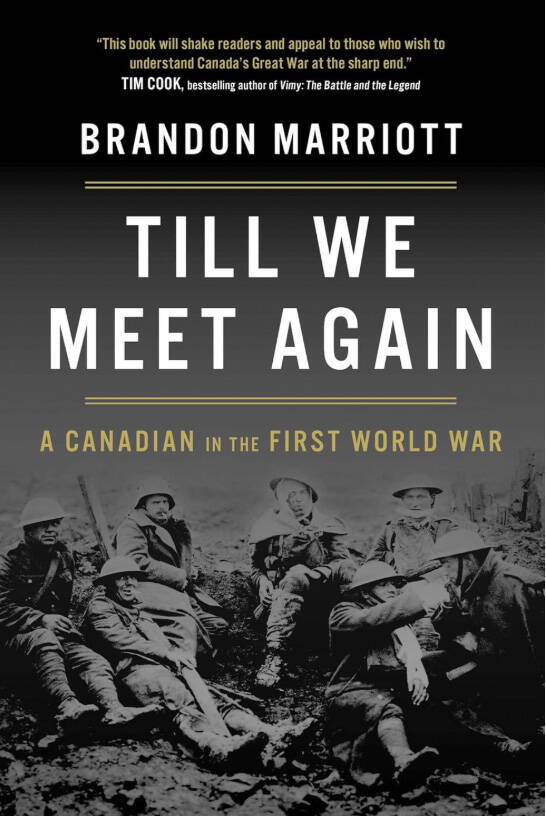

Soldier’s story reflects grim nature of life in the trenches

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

‘Every time I see the dead and wounded along the trenches, I feel sick at the awfulness of this war.”

These were the words of Lester Harper, a disillusioned Canadian soldier in the First World War.

Canadian-born historian Brandon Marriott reconstructs Harper’s wartime experiences, using an archive of more than 700 pages of letters written by Harper during the war.

Marriott was drawn to this subject because Harper was his wife’s great-grandfather.

The historian has pieced together an account of life in the trenches, the tribulations of ordinary Canadian soldiers.

One of its themes is how Harper’s attitude to war changed.

Before it left for Europe, Harper’s battalion was inspected in Ottawa by the prime minister, Sir Robert Borden, who gave an inspiring speech. Harper fully embraced Borden’s message that the Canadian army was going to Europe to fight for liberty and justice.

But life at the Western front soon disabused Harper of his youthful idealism. As Marriott writes, Harper “did not fight for the prime minister anymore. He did not fight for his country or ideals like justice and liberty either. He fought only for the men by his side.”

Marriott is skeptical about the British high command’s strategy, as formulated by Field Marshal Douglas Haig. Haig repeatedly ordered suicidal frontal assaults that resulted in millions of deaths. He was convinced that this war of attrition would lead to a breakthrough on the Western front. Eventually the breakthrough did occur, but at a terrible cost.

Harper began the war as a private, was promoted to corporal and then sergeant. He was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions in a raiding party.

When the armistice ending the war was announced, Harper was attending an officer training course in Bexhill-on-Sea. In a poignant passage, Marriott describes the emotions evoked by the war’s end: “At first, there was somber quietness, tearful reflection, and bitterness. The war had spared no one. Nearly every family had lost a son, a husband, or a father. Many had lost all three.”

The First World War was an epic human tragedy. Historian Marriott has written a sort of microcosm of the war, detailing the experiences of one soldier and his comrades.

The hardships and dangers they faced — poison gas, rat-infested trenches, shelling, assaults on enemy positions — are brought vividly to life. It is an unflinching depiction of the grim reality of war.

Graeme Voyer is a Winnipeg writer.