Slanted and enchanted

Exploration of indie rock’s history, from scrappy DIY recordings to lifestyle brands, hits all the right notes

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

‘I hear that you and your band have sold your guitars and bought turntables. I hear that you and your band have sold your turntables and bought guitars.”

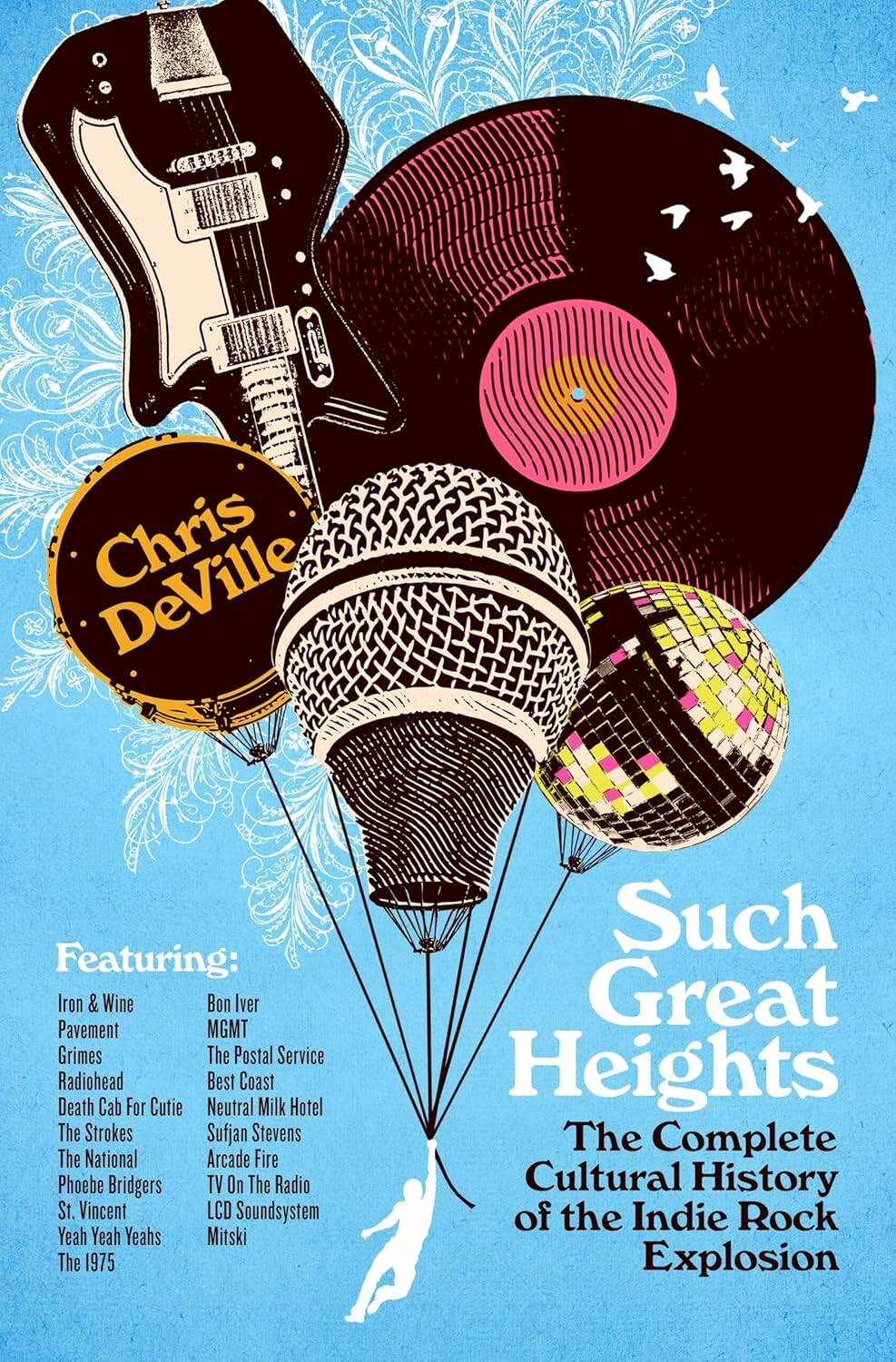

American music critic Chris DeVille quotes this LCD Soundsystem lyric twice in his ambitious debut book Such Great Heights. It’s a lyric that skewers the cyclical nature of cultural trends, and the desire — shared by musicians and listeners alike — to be the first to adopt a certain sound or aesthetic, and the first to discard it once it becomes uncool.

DeVille is a self-described “elder millennial” and the managing editor of Stereogum, an independently owned website that publishes music news, album reviews, artist interviews and trend thinkpieces.

Chris Walker / Chicago Tribune

In this 2016 photo, James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem performs at Lollapalooza in Chicago’s Grant Park.

He defines indie rock as “music released on independent music labels — i.e., companies not associated with the ‘big three’ major labels Warner, Sony, and Universal — or self-released without label support at all.” However, he quickly complicates that definition, showing how “indie” was always a fluid term, “less a defined musical style than a container for a particular audience’s evolving tastes.”

And evolve they do. One of the book’s central concerns is determining how and why indie rock went pop. Or, as DeVille puts it: “How did ‘indie’ music get from Pavement to Carly Rae (Jepsen)?”

The book , whose title comes from a song by indie darlings the Postal Service, proceeds in a loose chronological fashion. Chapters are prefaced with playlists and organized thematically. To cover 45 years of cultural history in around 350 pages, DeVille adopts a brisk pace and a bird’s-eye perspective, with a few personal anecdotes peppered in. Scene-defining artists and bands get three- or four-page treatments, while minor but influential players are explained in a couple of paragraphs.

Readers are whisked through the microgenres of the internet era including freak folk, blog rock, and synth pop. There are also clarifying forays into the cultural ecosystems surrounding indie rock, including what indie kids watched (The O.C., Wes Anderson films), how they discovered new music (Napster, iTunes, Tumblr) and where they shopped (thrift stores, Hot Topic, American Apparel). DeVille also unpacks key concepts in contemporary music criticism, such as rockism, poptimism, the twee aesthetic and hipsterism.

Befitting a book written by a Midwesterner (DeVille hails from Columbus, Ohio), the book’s tone is friendly, welcoming and self-deprecating — no snooty record-store clerk types here. DeVille is a deft summarizer, and his musical knowledge is vast. He has a knack for showing how one artist paved the way for another, and is good at identifying pivotal or symbolic moments in indie rock history, like when Beyoncé and Jay-Z went to a Grizzly Bear concert in 2009. But his critical analysis is largely confined to the periods he lived through as a fan and critic. Consequently, the book’s treatment of the past 25 years is stronger than its tour of the 1980s and ‘90s.

Much of the book is, unavoidably, concerned with technology. At first, hardware like iPods and software like Napster exposed listeners to a broader range of sounds. But as streaming algorithms replaced curated file sharing, it became harder for up-and-coming acts to break through. “The online world that had paved the way for indie’s ascension was starting to feel like a gentrified neighborhood where only those who’d already achieved success could thrive,” DeVille writes of the streaming era.

Such Great Heights

Thus, DeVille arrives at one of his central insights: a cultural history of music is also a cultural history of capitalism. Indie rock went from a scrappy way of releasing music to a neatly commodified lifestyle brand as powerful corporate interests took hold.

Devoted indie rock fans won’t glean a lot of new information from the book, but they will come away with a more organized view of how indie rock developed and diversified. At the very least, DeVille’s evocative descriptions of classic indie rock albums will have readers reaching for their headphones to refresh their memory, or discover those albums for the first time.

Jordan Ross is a Winnipeg writer, photographer and indie rock fan who hopes the National will eventually reschedule their cancelled 2020 concert at the Burton Cummings Theatre.