Couple’s emotional stakes put to the test

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

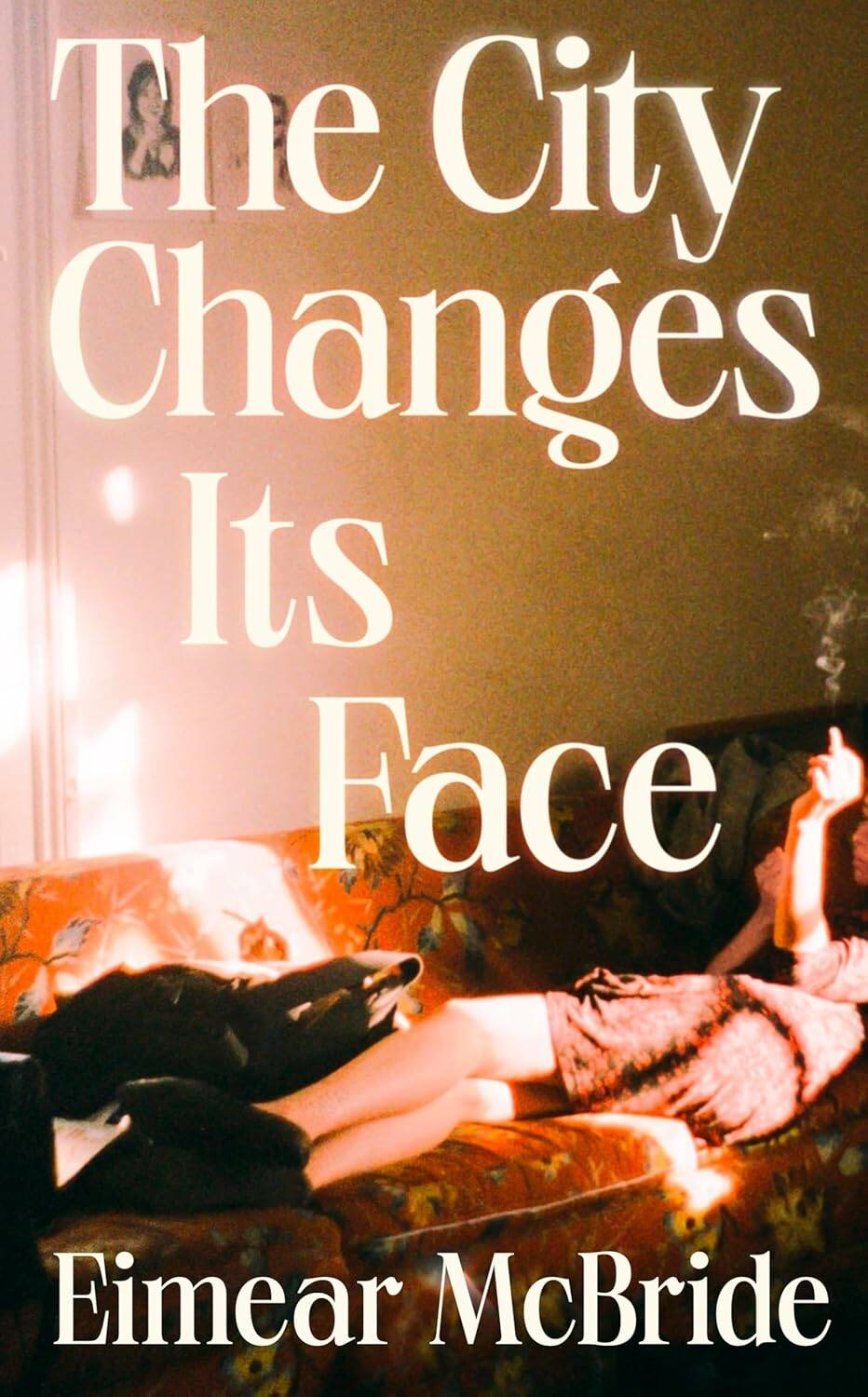

London-based Irish author Eimear McBride pulls no punches in her latest novel The City Changes Its Face. Set in a London flat over a long autumn night in 1996, two lovers — the book’s protagonist, acting student Eily, and her actor and filmmaker partner Stephen — expose the foundations or architecture (including sex, family trauma and addiction) of their relationship, re-living meaningful events, conversations and revelations over their first two years together. The novel is a gritty ode to the early passion of a lasting love affair.

At the novel’s outset Eily is particularly fragile; while many readers may intuitively anticipate the open secrets that shadow and conclude the book, the journey that takes us there is never easy or boring. Eily’s interior life is as embodied and as real as the tip-tapping of nervous fingers on the Formica counter, the fought-over ripped duvet, the city noises outside of the couple’s Camden flat and the tube, the Underground, shuddering below their feet.

Shirking convention, McBride presents her characters’ dialogue without tags and with unusual line breaks and spaces, forcing the reader to slow down and backtrack, to hang and consider the words and the heightened emotions and meaning that permeate these words. She also uses smaller font for interior monologue or asides that complement and contradict the words Eily shares with the other characters and the reader.

The City Changes Its Face

McBride revels in the subterfuge and esthetics of the performance that Eily and Stephen — as actors and artists — engage in presenting to each other and the world at large.

In the middle of the book, McBride takes readers to a film screening where Eily, along with her partner Stephen’s estranged teenage daughter Grace, watch the graphic autobiographical film depicting London, Stephen’s struggles with addiction and a dark family past. As the film is described by Eily, the book’s three main characters respond and react to what they see on the screen.

While in another book this may come across as heavy-handed, McBride for the most part manages to pull this long interlude off. The scene offers a layered insight into Stephen, interplaying truth, performance and art — the combination of which is not unlike what we experience in the heightened moments when we first fall in love and share our past and the darkest parts of ourselves with our partners.

The strong depiction of the film within the book convinces the reader of its stakes for all involved. For Stephen and Grace, it’s their origin story, a bridge upon which to build an honest, compassionate and hopefully healthy father-daughter relationship. As Eily tells us, for Stephen the film is freeing, and makes the past “no longer run like rats, biting away at your insights;” and as Eily confesses, for her the film is pivotal to her own future and offers a glimpse into the “want for other solutions to my faulty wiring,” which is at the crux of her crisis in the book.

McBride also doesn’t ignore the age difference between the characters: Eily is 20 and Stephen is 40. When Stephen reconciles with his teenage daughter, he and the two women face the complexity of the situation where Eily is closer in age to Stephen’s daughter than to him. While empathetic, McBride does not avoid the messiness of emotions affecting all three, and both Eily’s and Stephen’s unhealthy attempts to deal with this.

While The City Changes Its Face rehashes characters from McBride’s 2016 novel The Lesser Bohemians, it stands firmly on its own. Rarely does a book do so well walking the edge between inexperience, passion, jealousy, addiction, violence and abuse, while still reaffirming the risks worth taking in hope of working through these issues to achieve a caring, mature relationship.

Barbara Romanik is a writer and editor working and living in Winnipeg.