King’s love of architecture largely ignored

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

“Give this much to the Luftwaffe: when it knocked down our buildings, it didn’t replace them with anything more offensive than rubble. We did that.”

So spoke our present king, Charles III, to a British audience in 1987.

Constitutional norms dictate that the British (and thereby, Canadian) monarchy doesn’t involve itself in political or commercial matters.

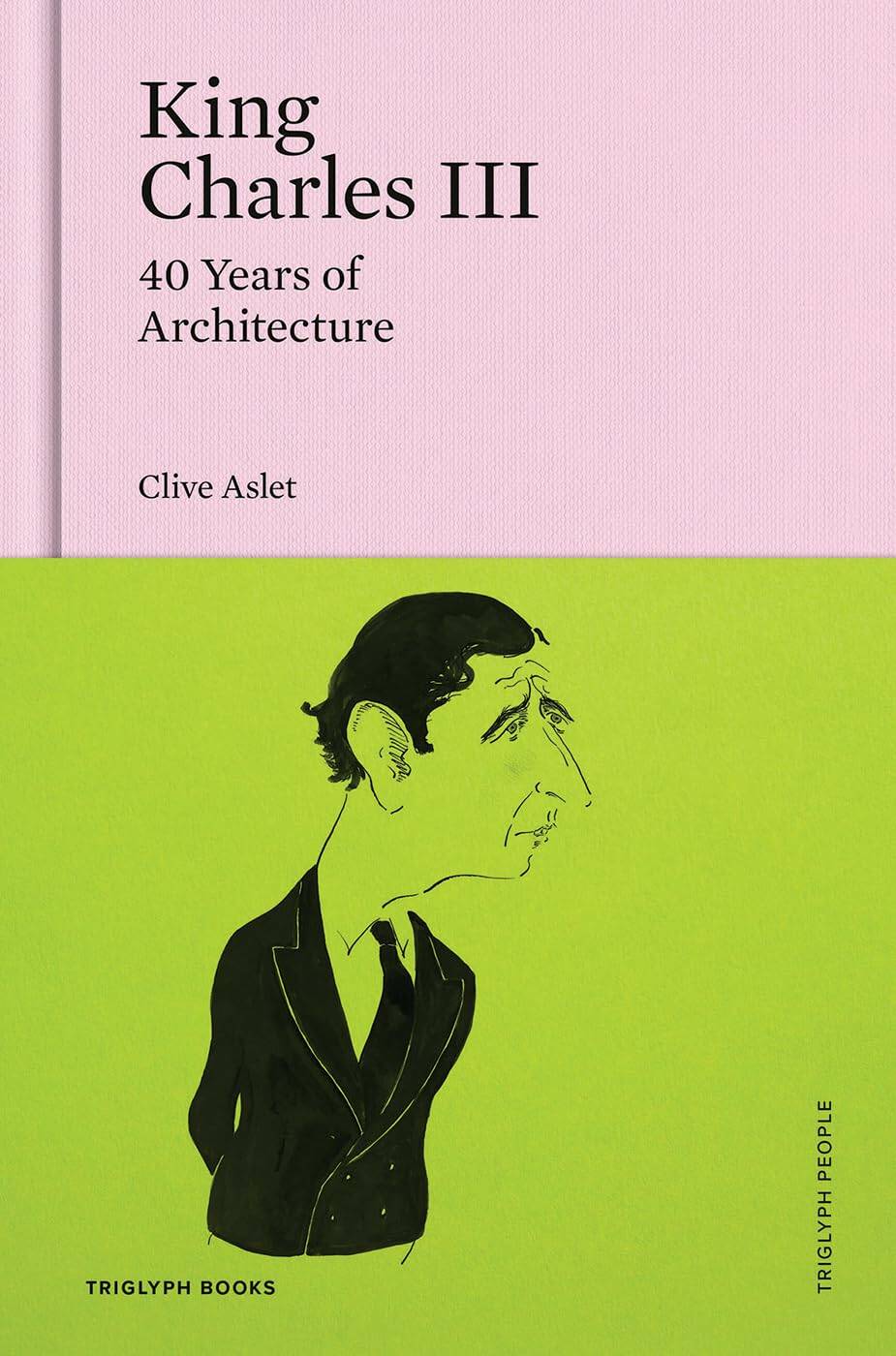

King Charles III: 40 Years of Architecture

Charles, when monarch-in-waiting as Prince of Wales, honoured that protocol — except when it came to architecture.

The Luftwaffe shot was neither his first nor his deadliest broadside against modern British architecture.

In 1984 he attacked the design of a proposed extension to the stylish National Gallery in London as a “kind of municipal fire station, complete with the sort of tower that contains the siren … what is proposed is like a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend.” His public tongue-lashing torpedoed the original planned extension.

British writer Clive Aslet, author of more than 30 books about architecture and aspects of Brit life, has tracked our king’s long engagement with building and landscape in a survey that manages to be lively and learned at the same time.

Early on, Aslet underlines he had no authorized access to the king or the “treasure trove of memos, lectures and annotated plans in the Royal Archives” that will be available to future scholars. But for all that, he does a bang-up job of tracing the life of a king who’s always been “big on architecture” by interviewing the architects, advisers, critics and academics who worked with him.

Charles was an apostle of traditional design associated historically with the Classical school of architecture, though he often qualified or modified his preferences via more contemporary environmental touches.

But his vigorous and informed engagement with architecture isn’t well known, especially outside of Great Britain.

The media focused on his fairy-tale-gone-fractious marriage to Princess Diana, his perennial romance with Camilla, his long — and allegedly frustrating — apprenticeship to ascend the throne and his wealth and privilege compared to the average Brit. His architectural endeavours were largely ignored and, if not ignored, given short shrift or belittled, according to Aslet.

The book, in large part, is an attempt to remedy that gross misapprehension. And it succeeds admirably.

Aslet chronicles Charles’s pivotal role in the creation of model contemporary housing, and exemplary urban environment, at Poundbury in Cornwall. He also details the then-prince’s involvement in the restoration and renewal of a heritage home and estate, Dumfries House in East Ayrshire, a project that also led to local economic regeneration through the launch of youth-training opportunities.

But most astonishing is his account of Charles’s abiding interest in architectural restoration and landscape preservation beyond the U.K.

Charles bought, and still owns, two village properties in Romania, specifically Transylvania, as part of his campaign to retain pristine homes and landscapes.

His rationale for the purchases: “It’s the last corner of Europe where you can see true sustainability and complete resilience, and the maintenance of entire ecosystems to the benefit of mankind and also of Nature. There’s so much we can learn from it before it’s too late.”

The portrait that emerges in Aslet’s recounting is of a king, and a man, far more complicated than the public gives him credit for.

Aslet never uses the word, but in his telling our king comes across, all for the good, as a bit of a maverick.

Douglas J. Johnston is a Winnipeg lawyer and writer.