Brisk prose, big ideas

Zadie Smith muses on art, politics, culture and late authors in new essay collection

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Bursting onto the literary scene in 2000 with White Teeth, Zadie Smith has gone on to write five more novels, including 2023’s The Fraud. The London-based writer is also an untiring essayist, having released several agile, insightful and far-ranging collections.

This latest batch, Smith’s fourth, includes reviews, articles, columns and talks. Some pieces feel like brief and breezy conversations with the reader; others are deep dives into fraught cultural and political intersections. As suggested by the title, there’s a particular focus on the way the past frames and forms our present moment.

Grouped under the headings Eyeballing, Considering, Reconsidering, Mourning and Confessing, the essays cover visual art, film, performance and, of course, books. Smith eulogizes Toni Morrison, Joan Didion, Philip Roth, Martin Amis and Hilary Mantel, all writers who have died in the last few years, and brings up many more.

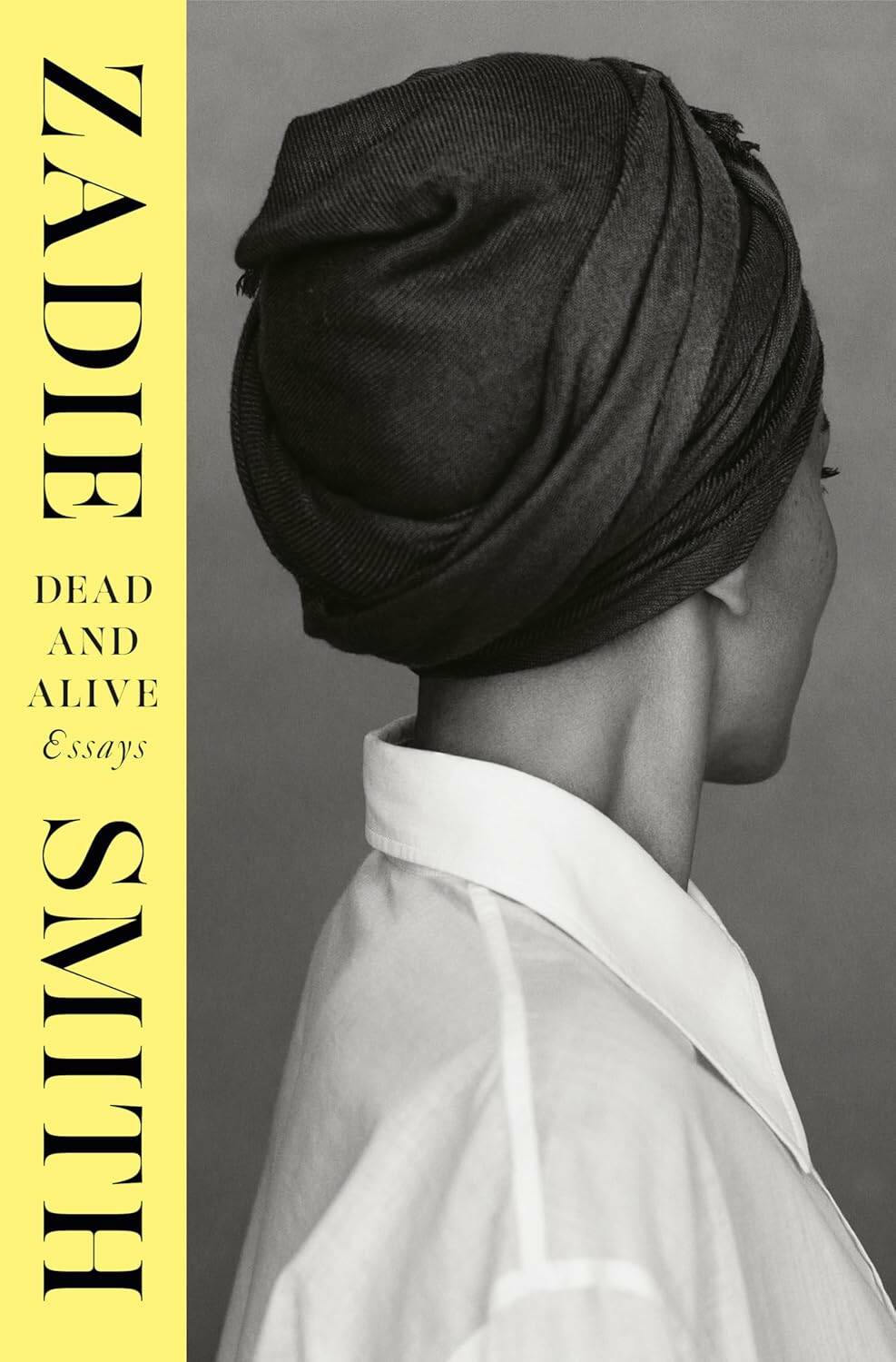

Ben Bailey-Smith photo

While Zadie Smith’s writing style is sharp, clear and specific, her thoughts are exploratory and open-ended.

Smith includes forewords she has written for the reissue of two crucial historical works, Gretchen Gerzina’s Black England and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan. She considers the labour and craft of writing, the serendipitous pleasures of urban walks — in New York City and her beloved northwest London — and the lures and risks of being Extremely Online.

In response to a magazine’s request to write on “agelessness,” the 50-year-old Smith slyly writes instead a defense of what might be considered “agefulness,” concluding that it’s “not easy, aging, but it is consistently interesting.”

What connects these sundry subjects is Smith’s approach, which is shaped by her distrust of absolute certainty. Her prose style is sharp, clear and specific, but her thoughts are always exploratory and open-ended. As her category headings suggest, Smith likes to consider and then reconsider.

Smith’s detractors sometimes view this tendency to see both sides of an issue as ideological shillyshallying. But for many fans, Smith’s old-school liberal humanism will feel like a needed respite from the either/or extremes of so much current discourse.

This habit of mind is perhaps most eloquently embodied in Fascinated to Presume, a passionate defense of fiction as an act of moral imagination and emotional empathy. Considering the currently contested question of who can write about whom, Smith admits that “fiction gave us Madame Bovary but also Uncle Tom.”

She recognizes the historic misrepresentation and under-representation of women and other marginalized groups in literature and the harms this has caused. But she’s also wary of the notion that a writer must only write about people “like oneself.”

“The old – and never especially helpful – adage Write what you know has morphed into something more like a threat: Stay in your lane,” she suggests.

And what does “like oneself,” even mean? Looking at the work of Elizabeth Strout, for example, Smith asks, “What do I have in common with Olive Kitteridge, a salty old white woman who has spent her entire life in Maine?

Dead and Alive

“And yet, as it turns out, her griefs are like my own. Not all of them. It’s not a perfect mapping of self onto book — I’ve never met a book that did that, least all my own. But some of Olive’s grief weighed like mine.”

While believing “a self can never be known perfectly or in its entirety,” Smith knows that readers and writers alike keep trying. She walks around this conundrum, grappling with her own need to understand, to connect, to imagine other lives and other experiences.

It’s that sense that Smith is thinking things through — and inviting us to do that, too — that animates her best writing. As with her novels, the essays in Dead and Alive are humane, generous and alive with curiosity.

Alison Gillmor writes on pop culture for the Free Press.

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.