Fabulously fluid

Williams explores changing notions of racial identity, sexuality and more in new novel

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

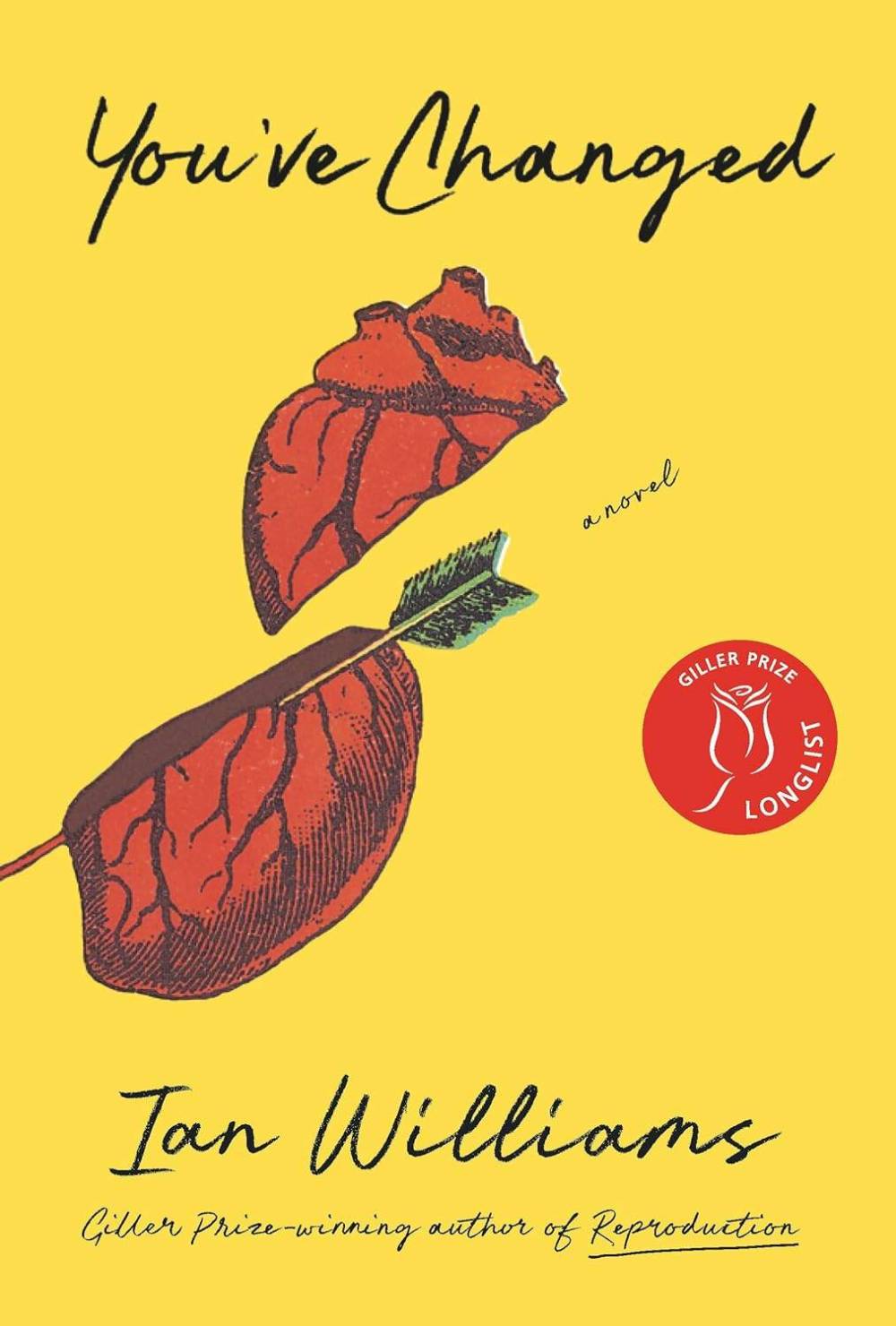

Like his debut novel Reproduction, which won the Giller Prize in 2019, Ian Williams’ eighth book, You’ve Changed, plays with form and reader expectations.

You’ve Changed opens as if mid-sentence, with a list of mundane tasks such as “tapping screens, setting appointments, trimming fingernails…” written in lighter text as if highlighted by an editor for possible changes. Throughout the book, potentially controversial words such as “gay,” “porn,” “hell” and “dick” are partially blacked out. Despite this self-censorship, William tackles many taboo topics in detail, such as urination and sexual incompatibility, which he approaches with irreverent humour.

William’s latest was also named to the long list for this year’s Giller Prize. He has won the Hilary Weston Prize for Nonfiction, and was chosen to deliver the 2024 CBC Massey Lectures. He teaches English and Creative Writing at the University of Toronto.

Zackery Hobler photo

In Ian Williams’ latest novel, the reader’s level of sympathy for each of the main characters shifts as the narrative point of view changes.

On the surface, You’ve Changed is a simple domestic drama about an ordinary married couple, Beckett and Princess, who have no children. Beckett works in construction, and near the beginning of the novel is fired for trying to help a fellow employee, who is being bullied by the boss. Princess is a fitness instructor at a gym. When Princess’ childhood friend Keza and her husband arrive for a visit shortly before Keza is due to give birth to their third child, the cracks in Beckett and Princess’ marriage begin to show.

The theme of change permeates the novel. Newly unemployed, Beckett attempts to start his own home renovation business, altering and improving peoples’ living spaces. Princess, meanwhile, is preoccupied with changing her physical appearance through plastic surgery. Having already had alterations made to her cheeks, lips, nose and breasts, she decides to go to Costa Rica to get a Brazilian butt lift. By the time Princess leaves, she and Beckett are experiencing sexual difficulties and are emotionally distant from one another.

The stage is set for the entrance of Gluten, a mysterious individual who upends Beckett’s sense of who he is and puts further strain on his marriage to Princess. The plot revolves around this love triangle; the symbolism is intriguing, as the triangle is the symbol of change in chemical reactions, and the sections of the novel are divided by triangle symbols, in varying rotations and patterns, on the page.

Numerous other changes take place throughout the novel. Princess is written as a deliberately unlikable character. Besides her obsession with physical appearance, she is competitive, immature and selfish. However, later in the novel, fortunes reverse and the reader may see her as a sympathetic character who has been wronged.

Likewise, at the beginning of the novel Beckett is portrayed as a repressed character with a trauma history who is steamrolled by Princess. But as the story progresses, his actions become less defensible.

The switching places of villain and victim coincide with the shifting of the point of view, beginning in third person, then moving to Beckett’s voice in the first person, and then to the third person written as Beckett addressing Princess. The reader’s level of sympathy for each character varies with the change in narrator.

Of course, this is true in real life too: when listening to someone detail their relationship difficulties, we tend to empathize with them rather than the other party whose point of view is not being shared. At times Williams takes the reader so deep into Beckett’s point of view that one feels more like a voyeur than a reader.

You’ve Changed

Princess’ racial identity also shifts over the course of the narrative. Here Williams plays with assumptions and deliberately sows ambiguity. Princess is presented as white at the beginning of the novel, though she grew up in Ivory Coast in West Africa, among other places. Later in the novel, Princess claims a Black identity, apparently based on her mother’s partial North African ancestry, which Beckett refuses to accept.

Sexuality is treated with the same fluidity as race, with Williams posing the question: does engaging in sexual activity with a partner of the same gender make one a homosexual, or can this sexual activity be confined to one person and circumstance? How much do our identities define us, and what is their influence upon our relationships? In this way, a seemingly quiet novel about Princess and Beckett’s marriage becomes a commentary on the wider world, leaving the reader to wonder whether the world itself has changed, or just our places in it.

The novel ends as it begins, with a list of quotidian activities which suggests that perhaps life does not change as much as we might think it does or wish it to. Maybe instead of hoping for more, we should be content with, as Williams writes, “taking out the recycling on Wednesdays, unlocking the truck, sending e-transfers…”

Zilla Jones is a Winnipeg-based writer of short and long fiction. Her debut novel The World So Wide was published in April.