Family, friendship and faith unpacked in fiction

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

In her 2024 short-story collection Things That Cause Inappropriate Happiness, South African-born, Toronto-based author Danila Botha introduced readers to a variety of women discontented with their relationships, their art and their lives in general.

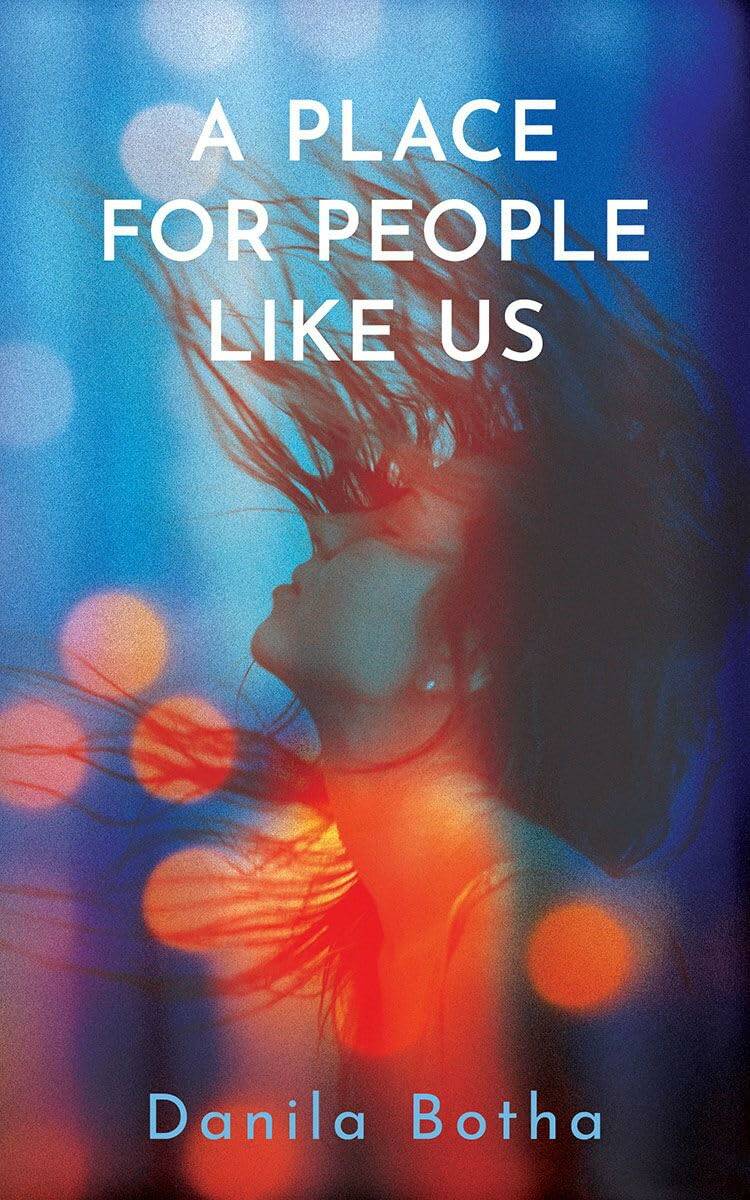

In her new and second novel A Place for People Like Us, Botha, who is on the faculty of Toronto’s Humber School for Writers, focuses again on unhappy and adrift young women and their intertwined and unconventional search for a place to belong.

Twenty-one year-old university student and part-time videographer Hannah first meets Jillian at a bar and is immediately mesmerized by the musician’s talent, exotic demeanour, erratic behaviour, passion and outgoing personality. The two women quickly become friends, then roommates and then occasional lovers, occupying themselves with art, drugs, drinks and thrill-seeking in the clubs and streets of Toronto.

A Place for People Like Us

Hannah is the more clearly drawn of the new friends. Having recently escaped a traumatic upbringing, she revels in Jillian’s easy offers of love and acceptance even as she recognizes the toxicity and co-dependent nature of their relationship. Jillian’s love and acceptance, and Hannah’s gratitude for them, however, begin to change when handsome Mark, who is also known as Naftali, enters the picture and starts vying for Hannah’s attention.

“I knew that in some way I wanted them both, the excitement of someone I couldn’t predict and the stability of someone else who would actually be there,” Hannah confesses to herself.

Like everything that occurs in this ambitious novel, Hannah’s new romance and her subsequent decision to convert to Judaism in order to be accepted by Mark’s observant family happen too quickly and too unrealistically. Botha seems to be attempting to justify the speed in which the novel’s events unfold by having Hannah explain, “I wish I could do things lightly or casually, but the way I’m wired, I go all the way or not at all.”

That explanation, unfortunately, doesn’t work well enough to counter the sense that the entire narrative is rushed and undeveloped. For example, Botha convincingly uses Mark’s unpleasant family members, and especially Hannah’s impulsive trip to Israel, to demonstrate the rigidness and hypocrisy of strict religious observance. At the same time, though, she misses the opportunity to explain to readers how and why orthodox Judaism is so connected to Jerusalem.

Similarly, Botha has Hannah befriend a Canadian Jewish woman who is deeply committed to raising awareness about Palestinian human rights abuses. But then, after a paragraph or two, in what seems like a blatant missed opportunity considering the real and fraught political polarization in diaspora Jewish communities today, Botha unceremoniously drops that character and her storyline from the narrative.

Events occur at an even more hurried pace when Hannah returns from her trip to Toronto. Her parents are finally introduced in a disturbing and improbable scene, Jillian becomes more needy and Hannah becomes more ambivalent and questioning about her future. She makes decisions. She changes her mind. She celebrates major life cycle events. She makes mistakes. She self-sabotages. And she worries about Jillian.

“The Jewish community is great if you want people to tell you exactly how to live our life down to the most minute detail,” Jillian tells her, “but if you’re weird and unique like us, it’s wrong. It’s not a place for people like us.”

Whether or not Jillian’s warning proves true is revealed in the last few pages of the novel, a work of fiction that, in spite of its moments of implausibility and awkward pacing, has much to say about both embracing and escaping family, friendship and faith whenever the need arises.

Sharon Chisvin is a Winnipeg writer, editor and oral historian.

The Free Press is committed to covering faith in Manitoba. If you appreciate that coverage, help us do more! Your contribution of $10, $25 or more will allow us to deepen our reporting about faith in the province. Thanks! BECOME A FAITH JOURNALISM SUPPORTER

The Free Press acknowledges the financial support it receives from members of the city’s faith community, which makes our coverage of religion possible.