Generations of pain permeate fraught Irish family

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

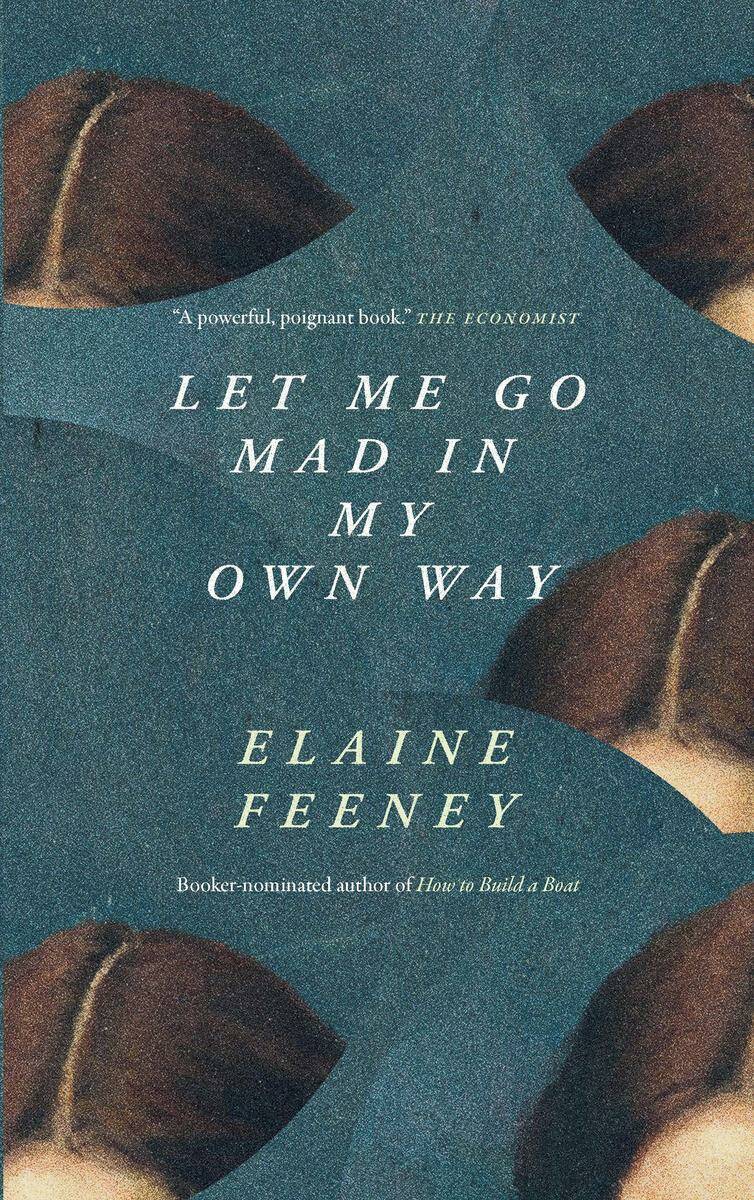

Irish author Elaine Feeney’s latest novel Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way has been described as a work of literary and cultural exorcism. Her character-driven novel is a profound exploration of family, history, violence and hope.

The principal character, Claire O’Connor, is a promising writer who left the family’s struggling farmstead in western Ireland for London, where she fell in love with another writer, Tom Morton.

Her life has been on hold since she broke up with Tom and moved from London back home to the rugged west of Ireland to care for her dying father. Claire is afraid to make a commitment to Tom and doesn’t want to become a “trad wife,” a group of women she has recently discovered on the internet holding very conservative convictions about the role of women in a marriage. But glimpses of her old life follow when Tom unexpectedly moves nearby.

Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way

Claire resisted pleas to return to see her sick mother. When her mother dies, she learns she starved herself to death rather than look after Claire’s sick father.

Full of regret, Claire returns to care for her father who is dying of cancer. He’s permanently angry and is always quick to blame his troubles on someone else, refusing to take responsibility for a problem. And he never hesitated to blame his wife and beat her.

With richly textured description, Feeney takes readers through several layers of troubled Irish history and suffering across generations, including the potato famine and fights both with the English and each other. For her Irish characters, the troubles of the past are never far from the tips of their tongues. When a guest at a party suggests the Irish could at least walk to the sea to get fish, she is quickly put in her place when Claire responds “Hard to walk twenty miles when you’re starving to death.”

When Tom is visiting Claire’s old home, he notices writing on the wall: “I killed the pig of the pigs.” When he reads it out loud and asks what it means, Claire’s brother Conor becomes outraged, and the other brothers try to stop him from attacking Tom.

The reference is to a Black and Tan raid on the house one night during the Irish War of Independence (1919-21) in a search for guns; one brother was killed, and their mother, who was hiding the gun, was raped by the group. Before the Black and Tans were done, they killed the family’s cow and pig.

There’s a lingering animosity to the British; after a fox hunt, Claire’s father John O’Connor receives an offer to buy his horse, but he knew “selling to the Queen would be the worst tainting on the name of his family since he time some of the locals had taken soup during a famine that slaughtered the countryside.”

Claire softens her feelings about her father, who dropped out of school at 14 and was married at 19. “I forgave him in the bedroom before he died… I didn’t tell him. He wasn’t looking for forgiveness. He burned on until the end,” she says. “I reasoned that I didn’t know what it was like to raise a family on a few acres of stone and rock. I didn’t fully know what kind of wage package a postman got, or what he had been through, what had set such an unquenchable anger in him… was it fear of not having enough to cover the basics?”

Overlapping all of this is the global pandemic, which forces isolation and which adds to the accumulated trauma.

Readers might well wonder what else can happen in this seemingly eternal see-saw of love and hate.

Gordon Arnold is a Winnipeg author. When his paternal grandfather was one year old, his parents emigrated to Canada from western Ireland, settling several years later on a farm near Somerset.