KGB archivist’s deceit both personal, political

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Vasili Mitrokhin was an obscure, nondescript archivist for the KGB, the Soviet secret police and espionage organization, which he dutifully served from the late 1950s to 1984.

But appearances were deceptive.

From 1972 to 1984, Mitrokhin took the risk of making copies of top secret KGB files. The copies were painstakingly written on small sheets of paper which Mitrokhin would cram into his shoes.

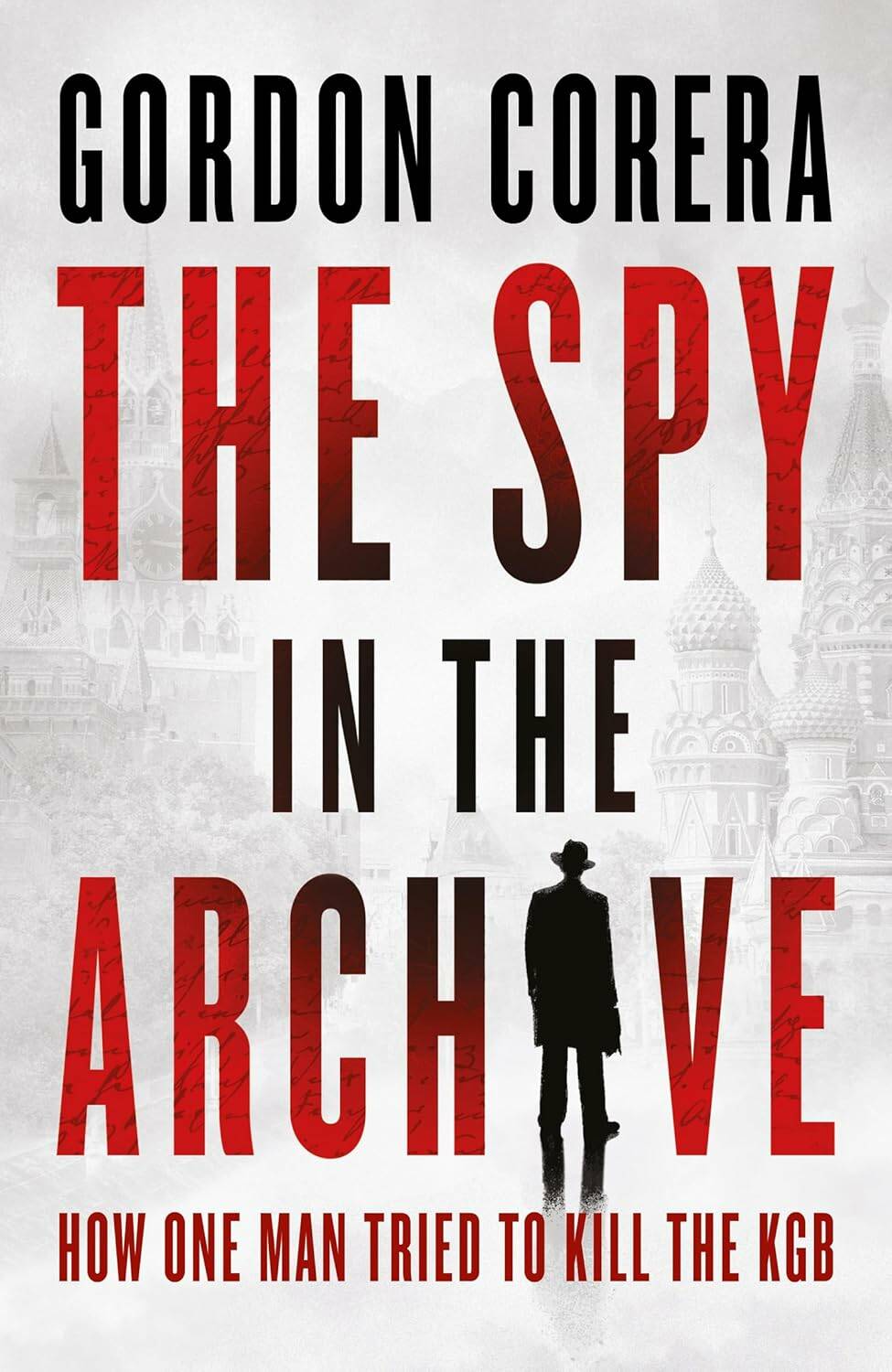

The Spy in the Archive

He compiled a massive archive that he would eventually deliver to British intelligence, greatly harming the operations of his erstwhile employer.

Mitrokin’s amazing story is recounted by Gordon Corera, a British journalist and former BBC correspondent, in a riveting account.

Why did Mitrokhin risk certain death? Corera explores the archivist’s motives, which were a complex blend of the personal and political.

When he first joined the KGB, Mitrokhin expected to travel the world as a frontline spy. But after some missteps, he was banished to the archives, a dead-end job. This demotion rankled.

But there was much more to Mitrokhin than frustrated ambition.

Indeed, he observed, “it was working in the archive that opened my eyes and allowed me to see the truth.”

He had access to the KGB’s response to the famous Prague Spring of 1968, a movement of reformers in Czechoslovakia seeking a less repressive form of socialism than that enforced by Moscow.

Increasingly, the KGB was prioritizing the crushing of domestic dissent, de-emphasizing counterintelligence in the West. This shift incensed Mitrokhin.

The archivist identified as a Russian patriot; he had a profound conception of traditional Russia, ancient and spiritual. The Russian Revolution of 1917 had imposed the Soviet regime on that traditional Russia.

The regime, for Mitrokhin, was a monster, and he saw himself as a peasant hero of Russian folklore who alone understood the nature of the beast that was tyrannizing the Russian people.

The monster had three heads: the Soviet Communist party; the Soviet elite, known as the nomenklatura; and the KGB. This monster had enslaved the Russian people; Mitrokhin hoped to destroy the monster by revealing the truth through the archive of KGB files he had covertly accumulated.

Mitrokhin had an additional, more personal motive: his son suffered from some sort of neurological condition that was never clearly diagnosed. By defecting to the West with his family, Mitrokhin thought he could secure better medical care for his son.

Corera points out the similarity between Mitrokin’s views and those of the dissident Russian novelist Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Both were devoted to a Russian mythos that predated the Soviet era.

The only criticism of this book is stylistic: Corera has a penchant for misplaced commas. That aside, he has evoked the tensions of the Cold War in a taut narrative.

Graeme Voyer dedicates this review to the memory of his Uncle Mike, a great and good man.