A lens on the North End

Winnipeg filmmaker discusses book reissue, creative process

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/09/2017 (3007 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It has been nearly 10 years since award-winning Winnipeg filmmaker John Paskievich captured the heart of the North End, the neighbourhood where he grew up, with his ever-present camera.

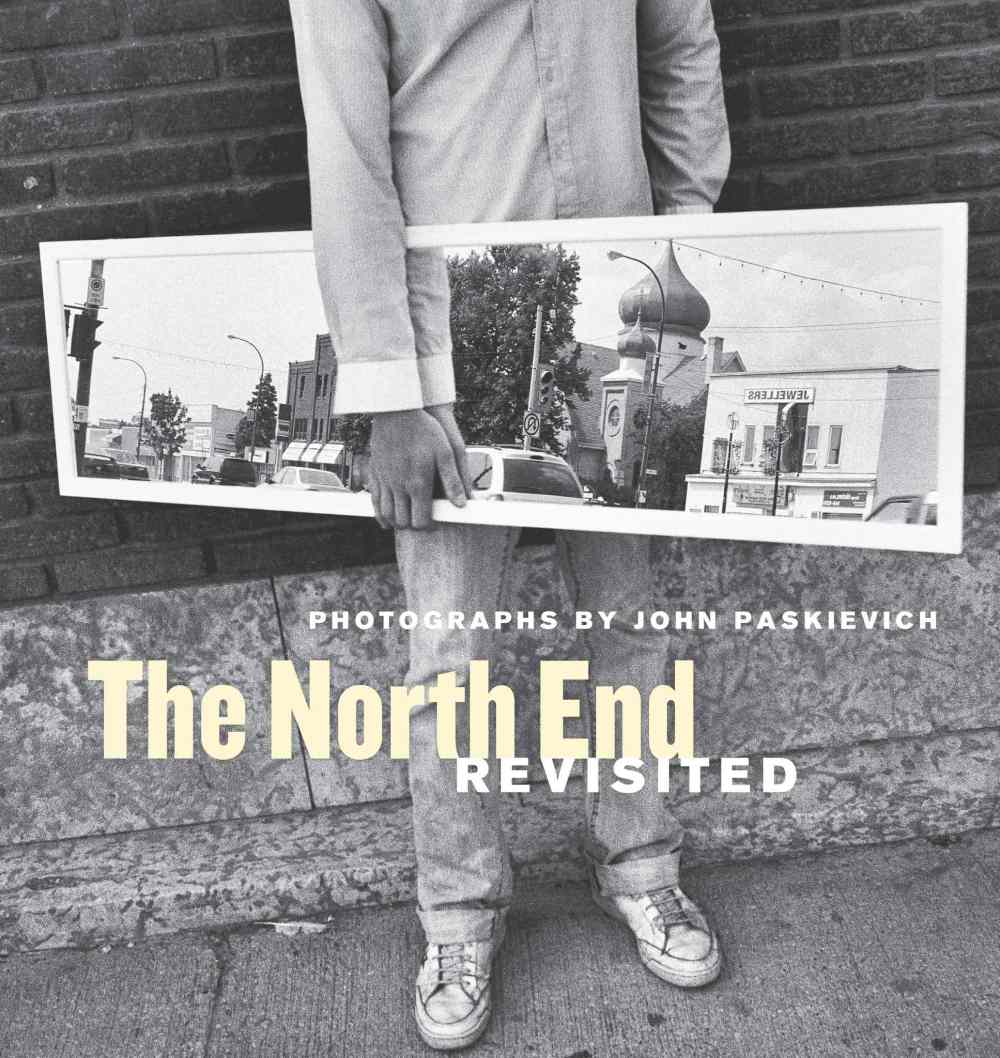

In celebration of University of Manitoba Press’s (UMP) 50th anniversary, a revised edition of his critically acclaimed book is being released this month featuring 80 new images. Aptly titled The North End Revisited: Photographs by John Paskievich, the book reminds us the North End is where the boundaries of ethnicity, class and culture crossed between Indigenous Peoples and Old World immigrants and helped define the city’s character.

A book launch is scheduled for Oct. 4 at 7 p.m. at McNally Robinson Booksellers.

Recently, we had the opportunity to chat with Paskievich about the “new” book, current projects and being nominated in the Short Film Palm d’Or category for the 1982 Cannes Film Festival.

This interview has been edited for length.

.jpg?w=1000)

Q: The North End, the first iteration of it came out in 2007. How did the idea of doing a revised edition come about?

A: Well, it wasn’t my idea. (UMP director) David Carr called me. He said because it was the anniversary of the UMP, they were going to publish a couple of books in celebration of its anniversary.

They thought of redoing the North End book in another way with some more copy and some additional photographs and dropping some of the photographs that were in the original book.

Just a bit of a change in the book.

Q: Did it feel like travelling back in time, looking at these images again?

A: Yeah, (it felt like) travelling back in time. And what’s interesting about photography… a photographer will tell you that (they) remember exactly how (they) felt when (they) took that picture.

It’s really amazing. This isn’t just unique to me. Other photographers will tell you (the same thing).

.jpg?w=1000)

Q: What other projects do you have on the go? In an interview you did in 2014, you mentioned you had a collection of Inuit photographs and there was a possibility of putting together a book.

A: Yeah, I was working for the federal government back in the ’80s to take pictures of the Inuit carvers and artists, and I did that.

And I took a lot of pictures on the side, for myself. I handed them all in to see what they wanted.

We were actually going to do a book with the UMP on these carvers, on my photographs from the Arctic. But then, (the 50th anniversary celebration came up) and so that’s been put on hold.

Q: Is there anything else that piques your interest that you’re considering pursuing?

A: Well, I’m working now on a film. It’s a film about Ukrainian-Canadians coming of age during the Second World War. What happened is that minority groups, before the Second World War, were still “suspect.” People like the Chinese, the Japanese, Aboriginals, and (Ukrainians served in the) Second World War where they died or got wounded. When they came back, the attitude (towards them) changed.

I can’t speak for the other minority groups but for the Ukrainians, it changed. It was more positive. Employment was more accessible to them. They could get jobs with the police force, the fire department and government jobs when before it was off-limits, especially for the Chinese. Because Ukrainians were white, they had that advantage. But still, a lot guys changed their names in order to be hired.

.jpg?w=1000)

Q: Have you done any filming for it yet?

A: It’s gonna be a bit of an experimental film because all the veterans, most of them, have died. There are little memoirs being done, letters and various things and so using still pictures and archival material without any veterans talking. It’s a challenge but we’ll see how it goes.

Q: So, the presentation of this film would be along the lines of your first documentary, Ted Baryluk’s Grocery?

A: Something like that, yeah, but also in the kind of Ken Burns way, you know, the moving camera over still pictures. We’ll see how it goes because the material is quite scattered and in bits and pieces.

I have no idea how long the film will be, but as long as it gets the point across, in a good way, I think it will be worthwhile.

.jpg?w=1000)

Q: What drew you into documentary film as opposed to doing feature films like the kind you see in movie theatres?

A: (I’ve always done) documentary stuff, I started with still photography and then after that little grocery store film, I got exposed to documentary film.

I liked documentary film and the kind of photography that I was doing (at the time). The demand for that kind of work started getting less. It was all about television. So, I went into documentary film and I just did photography for myself and I liked that balance.

Q: There seems to be a theme with the subjects of your documentaries, of being disconnected, of being an outsider within their communities.

A: That’s a theme I’ve always been interested in. I’ve always been interested — to my detriment sometimes — more in outsiders than insiders.

I like outsiders. I’ve always liked outsiders. They surprise me with what they know and what they’ve experienced. I find them very interesting. It broadens me in all ways.

I’ve always been interested in outsiders, people who are supposedly marginalized or on the outside whether it’s ethnic groups or people with disabilities. I’m drawn to them which, I guess, makes me an outsider, too, in a way. It’s a part of me.

.jpg?w=1000)

Q: In an interview I read, you said all documentaries are fiction.

A: Yeah, they’re all fiction. They’re fiction based on a truth. You know, everything is edited — how you shoot, what you select. You construct it so you can have a story. (You have) a journalist, a photographer, a filmmaker… you have different people to send out to do the same story and they’ll come back with three different interpretations of the truth. Supposedly.

So then you say, “well, is it truth or is it fiction?” It’s a construction is what it is, of what the person thinks is their truth.

If you take a picture of a person one way, the person appears a certain way. The next shot, the person will look another way. People looking at that picture will come up with their own truth about the picture and their truth will be a fiction, too, because they don’t really know that person. It just goes round and round.

But, there is in all that stuff, there is truth in there. You have to be careful about what is the truth. More so in documentaries because in documentaries, the idea is that it’s objective. But it’s not.

Q: With regards to Ted Baryluk’s Grocery, it had been up for the Short Film Palm d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1982. How did that come about? How did it get into the selection process? Was that something you had a hand in?

A: No, I didn’t know anything about that. It was submitted by the National Film Board.

My partner and I, (co-director) Mike (Mirus), we were in the cafeteria at the film board and they made an announcement over the intercom like in school. Everybody cheered. It was a surprise.

.jpg?w=1000)

Q: That’s really cool since a number of photographers regard that film as the first great example of multimedia.

A: Yeah, the idea was originally that I was going to do a photography exhibit and then we were going to have this soundscape of the store as you went into a room. And then we were thinking, well, we got pictures, we got sound… we were wondering instead of putting it into a room, just put it together and make a film.

And everybody thought it was a wacky idea. And so we had a hard time finishing it. Getting money to finish it.

But when we finished it, it turned out well.

Q: Wacky idea?

A: Yeah, people turned it down. Well, the National Film Board turned it down three times. We just kept going back to them.

.jpg?w=1000)

Q: Was there a cooling-off period? Here’s your first kick at the cat and then they say ‘no’. How long after they said ‘no’ did you resubmit?

A: Oh, about a year, a year and a half. Then another seven months (after the second “no”).

Q: So these images were actually taken in late ‘79-‘80?

A: The film came out in ’82. Yeah, they were taken (around that time). And then in ’80, I went away to Eastern Europe. I was working there and I came back. So it took a long time to finish that little 12-minute film. A long time.

So, for the young people out there — persevere. Yeah, you gotta persevere because everybody will tell you it won’t work. Well, not everybody. Somebody will say it’s a good idea. That means a lot.

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

Kittie Wong is page designer and web editor at the Free Press. A graduate of Loyalist College’s photojournalism program, she worked at The Canadian Press’ picture desk before joining the Free Press in 1994. Read more about Kittie.

Every piece of reporting Kittie produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.