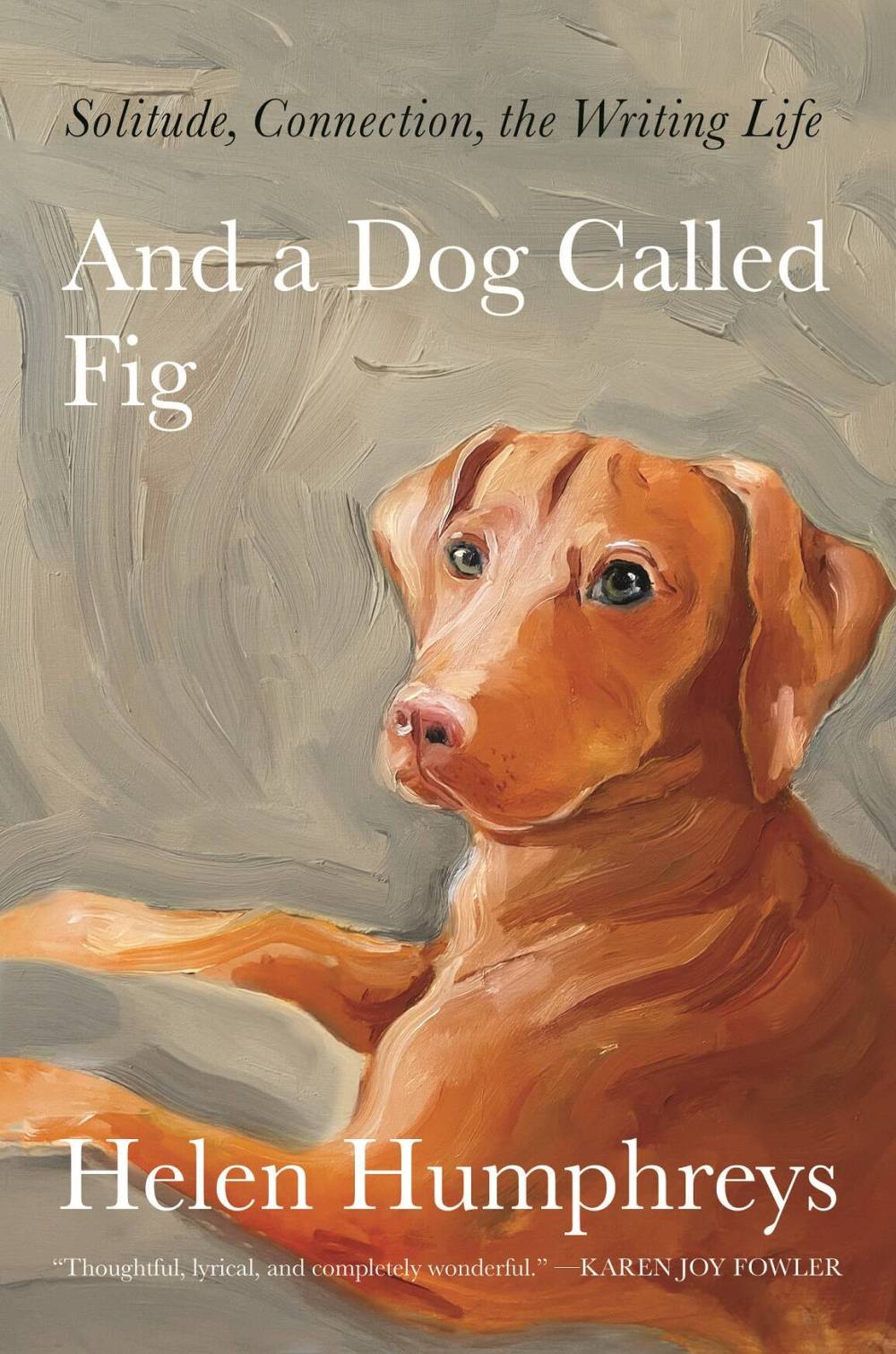

A different breed

Humphreys’ memoir explores writerly life in connection with four-legged friends

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/03/2022 (1382 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Part memoir, part extended essay, this quiet, understated book makes the case for the natural bond between writers and dogs. “In order to open myself to the thoughts and feelings that are necessary to the work, I have had to turn away from people,” novelist and poet Helen Humphreys relates. But she can still find wordless companionship with the dog lying at her feet.

After the death of her beloved Charlotte, a model of canine common sense and calm, the Kingston, Ont.-based Humphreys (The Evening Chorus, Afterimage) decides to take on a puppy, whom she names Fig. Like Charlotte, this new addition is a Vizsla, a type of Hungarian hunting dog. Unlike Charlotte, Fig seems intense, wary, all wired up. With this breed, Humphreys suggests, “the line between ‘high-strung’ and flat-out nuts is quite thin.”

And of course, Fig is still very young. “A puppy feels like a kind of disaster, and all response to it is in the disaster mode,” Humphreys writes. Overwhelmed with the biting, the crying, the chaos, she wonders about what she’s taken on. Even when she starts to feel a growing bond with Fig, she worries it might be a form of Stockholm Syndrome.

Humphreys muses on other dogs. She recalls the family dogs of her childhood, including a string of German Shepherds, each rather ironically called “Lucky” because they all died accidentally and young.

In the most entertaining portions of the book, Humphreys looks at the canine companions of famous writers, from Virginia Woolf’s rescue mutt Grizzle to Thomas Hardy’s terror of a fox terrier, who walked on the dining table, stealing food from guests’ plates. She relates that Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s cocker spaniel Flush viewed Robert Browning as a rival and bit him hard, twice.

She describes E.B. White’s imperious dachshund Fred, who “did not even seem to like White very much, except in an opportunistic way,” Humphreys suggests. As White himself wrote: “Fred devoted his life to deflating me and succeeded admirably.”

Humphreys’ tone is unobtrusively observant and emotionally restrained. You won’t find Marley & Me levels of sentiment here. Her prose tends to simplicity and lucidity.

She divides the book into sections that connect the process of puppy training with the process of writing (Beginnings, Structure, Process, Setting, Pacing, Ending). The connections sometimes feel forced, though, and Humphreys doesn’t have a lot to say about the nitty-gritty realities of writing.

Describing the focused intensity of hunting dogs who impale themselves on tree branches because they are so intently following game, for example, Humphreys writes, “I have wondered if it is perhaps the same feeling I have when I am writing well, which is a kind of crashing through the undergrowth, although far less dangerous.” One gets the sense she mostly wants to talk about dogs, but feels obligated by the book’s subtitle to connect her dog discussions to the literary life.

Humphreys is on much firmer ground when she talks about how a dog can break up the desk-bound routine of writing. “Walking the dog became the punctuation in the writing day,” she suggests, and her accounts of rambles in a nearby conservation area demonstrate her sensitivity to the natural world, which is often a theme in her other work.

Humphreys’ thoughts on dogs and happiness are also poetic and profound. She writes that some of her purest feelings of happiness have come when she is out walking with one of her dogs: “It is about a sense of being notched fully into the present moment, with no thought or desire outside of that.”

Free Press pop culture writer Alison Gillmor has to go walk her dog now.

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.