Adoption experience frays fraught family bonds

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/10/2019 (2229 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

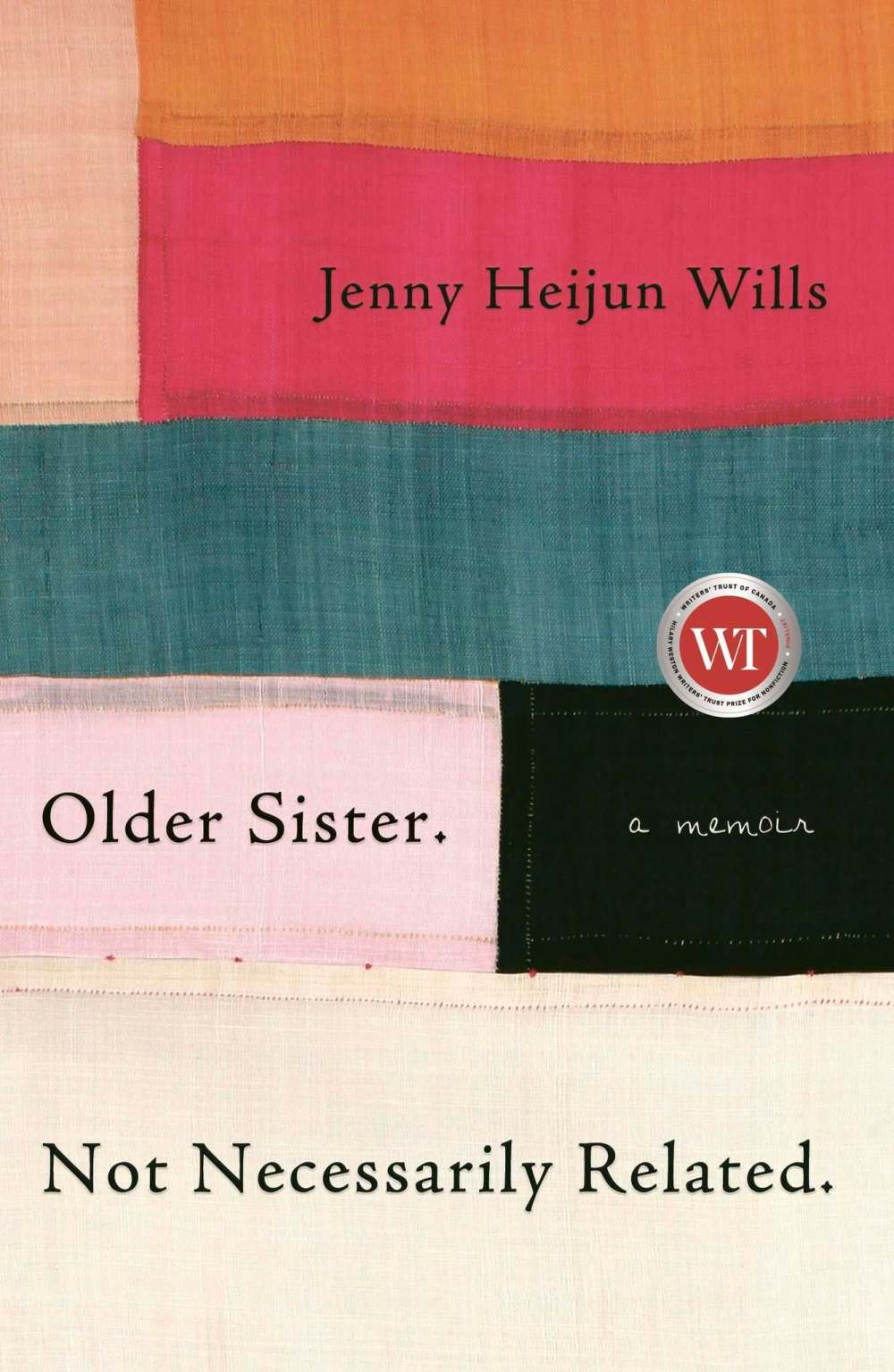

Artfully presented as a series of loosely chronological vignettes, Jenny Heijun Wills’ memoir Older Sister. Not Necessarily Related. chronicles her story as a transnational adoptee. Wills was born in Korea and adopted into a white Canadian family when she was six months old (she currently teaches at the University of Winnipeg), and Older Sister reveals the intricacies of her return to Korea to reconnect with her first family and piece together her personal history. The book was shortlisted for the Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize for non-fiction, which will be awarded Nov. 5.

“What is a life when all the stories come out of order and many… are hidden still?” she asks, pointing to both her own story and the form through which she tells it. Though all memoir writing is necessarily incomplete, Wills’s negotiations with selfhood hinge on not only her separation from her Korean family, but on the uncertainty of reassembling, in words, something she cannot name. She shoulders the weight of her expectations, and how her absence feeds her fear of erasure as a daughter, a sister and a Korean woman.

Even prior to the reunion, Wills navigates tangible bonds rooted in loss, narrating her intense experiences living in a guesthouse with others looking for their own family members where, she notes, “adoptee loss was concentrated.” Here kinship, support, rage, grief and violence all converge, as the guests face the precariousness of searching for relatives they might never find. Though the stakes are already devastatingly high here, they are even further compounded by larger issues surrounding culture, race, ethnicity, gender and class.

An entire page is devoted to the following four lines: “My question is, why? But I know there is no answer. At least not to me. Colonialism. White saviourhood. Orientalism. Impatience. Far-away birth mothers. No take-backs. Which is it?” Naming the many structures around which this narrative revolves is a deliberate, bold move on Wills’s part, but to simply call her story brave means acknowledging the many uncomfortable truths of which she speaks. “Do you know how much people are still willing to pay?” she asks, ever aware of the ways in which the transactional nature of her adoption does not account for her humanity, or that of her Ummah (mother).

Wills also uncovers how for her, the Korean language is yet another transactional barrier, as she sees it “blossom so effortlessly in the hands of non-Koreans” while she struggles to learn it, instead experiencing yet another type of distance between herself and her family. Notably, the devastating story of Wills’s birth as told, unprompted, by her Ummah, comes through a translator. Later, she mentions how she and her sister Bora “developed an intimacy without the burden of words,” often bonding over restaurant meals and homemade dinners.

The author’s relationship with food, though complicated in its own way, also provides solace and affirmation. Quiet passages about Korean food in particular resonate with the same visceral immediacy as more emotionally fraught moments. The act of passing food culture down through generations also eludes language — as Wills remarks, “there were no words to describe the way Ummah held a leaf of cabbage in her left hand, bisecting it down its spine mid-air with a cleaver.” She later notes, when cooking Korean food for friends, “the habitual food that (her) hands now knew without thinking was the food (she’d) learned to eat and cook and love as a grown woman. And that felt very real.”

By reconnecting with her Korean family as a grown woman, Wills also experiences new and habitual ways in which “performing gratitude and happiness, and hiding sorrow, also hurts.” Though these feelings are common within most family dynamics, they are also amplified when the author’s reappearance obliges her Korean family (and her biological father in particular) to renegotiate their respective identities as well.

While reflecting on that which families, in various incarnations, might owe to each other, Older Sister. Not Necessarily Related forges and mourns familial bonds in necessarily relatable and devastatingly exceptional ways.

Winnipeg’s Nyala Ali writes about race and gender in contemporary narratives.