Argentine activist’s disappearance detailed

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/04/2022 (1288 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

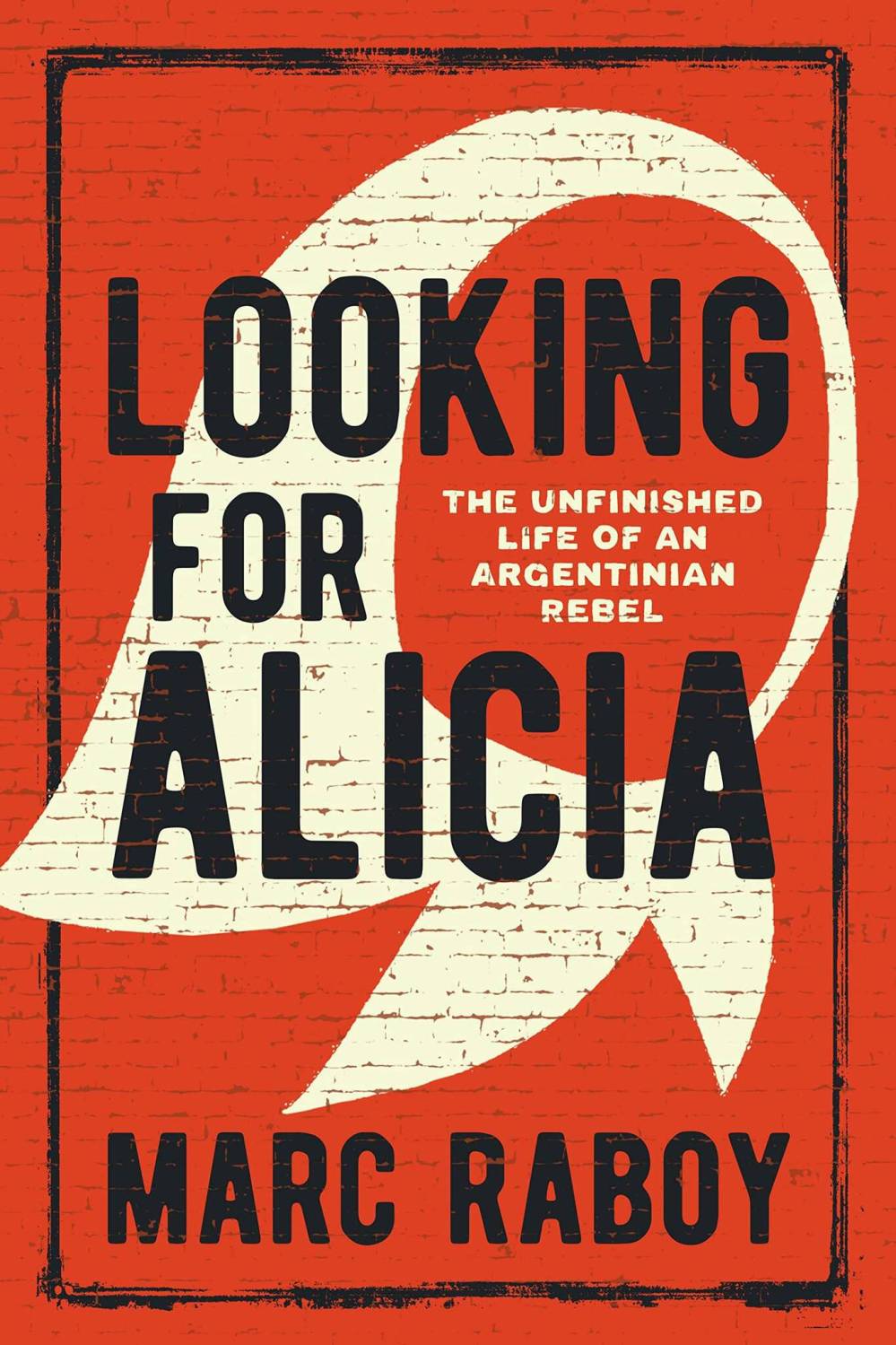

It’s estimated that more than 22,000 activists were killed or “disappeared” by police and military in Argentina between 1975 and 1978. In Looking for Alicia: The Unfinished Life of an Argentinian Rebel, Canadian author Marc Raboy writes of his search to uncover the story of his distant cousin Alicia Cora Raboy, who was last seen on June 17, 1976 when she, her husband Francisco (Paco) Urondo and infant daughter Angela were caught in a police ambush.

Urondo, a poet, author and one of the leaders of the Montoneros, a left-wing guerrilla group, was killed by a blow to the head. Angela was taken by police to an orphanage and later rescued by her grandmother, while Alicia was captured but vanished. Like many other Argentinian activists, Alicia’s ultimate fate was death, but no specific details have ever emerged.

It took until 2011 for the couple’s relatives to get any justice for their deaths. Four former police officers were convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment for Urondo’s premeditated homicide and the “illegal deprivation of liberty” of Alicia. A month before this judgment was made, a plaque was placed outside a high school in Buenos Aires commemorating the disappearance under dictatorship of 20 former students, including Alicia.

Raboy, Beaverbrook professor emeritus in art history and communication studies at McGill University, is the author of 20 books and a finalist for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Non-Fiction. A former journalist, he thoroughly details the political turmoil that existed in Argentina for much of the 20th century, including six military coups that took place between 1930 and 1976. It was in this environment that Alicia, born in 1948 — the same year as the author — became active in politics beginning at age 14, when she joined the youth wing of the Communist Party of Argentina.

Alicia and Raboy both grew up in immigrant Jewish families with ancestral roots in the province of Podolia in southwestern Ukraine. Alicia’s father was orphaned at a young age and adopted by an aunt and uncle in Argentina, arriving in Buenos Aires in 1925 at the age of 12. Raboy’s grandfather emigrated to Canada in 1914 and his wife and children, including Raboy’s father Sam, joined him in 1920.

Raboy is helped in his research into Alicia’s life by her daughter, Angela, and Alicia’s older brother Gabriel. Raboy realizes that he and Alicia also shared a passion for student activism, but in his case the political environment in Canada wasn’t as dangerous for young rebels.

“In Canada, one could imagine changing the system without putting one’s life on the line. In Argentina, trying to change the system was life-threatening. Alicia and I were separated by circumstances. She ended up in Argentina and I did in Canada, and that made all the difference.”

While over 45 years have passed since Alicia and Urondo were ambushed — two among thousands of other victims of government-sanctioned violence — Raboy witnesses the Madres de Plaza de Mayo’s weekly march in Buenos Aires’ main square. These now-elderly women, wearing white kerchiefs and holding signs, have walked every Thursday since 1977 in a public action meant to draw attention to their continuing demand find out the truth behind their relatives’ disappearances. In 2004, then-president Nestor Kirchner issued a formal apology in the name of the Argentine state for its failure to adequately address the crimes of dictatorship, and trials for human rights abuses under the label of genocide started in 2005.

Looking for Alicia is most interesting when Raboy links Argentina’s bloody history to the real lives of Alicia, Urondo and their families, but the book also contains detailed information on the country’s political history. It’s difficult to keep track of whether the left, right or middle is in power and also the roles of a multitude of activist groups. A useful chronology listing the key dates of Argentina’s history is placed at the end of the book.

Andrea Geary is a freelance writer in Winnipeg.