Into the light

Winnipeg's Assiniboia Indian Residential School was the last stop on a miserable, dehumanizing journey for many Indigenous youth; for some shattered lives, the outlier facility's freedoms and amenities arrived far too late

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/03/2021 (1678 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Excerpt from the preface of Did You See Us? (University of Manitoba Press), which was released this week.

As a prelude to the historical context of remembering the Assiniboia Indian Residential School, we must recall the events and reasons leading up to the establishment of an Indian residential school in a large metropolis like Winnipeg.

This history reveals the impacts experienced by children, families, parents, and grandparents of both the colonizers and the colonized. It must be a continuing narrative for history’s sake. This is not the beginning story nor an ending story, but a true depiction of a central part of a history now embedded in the collective library of knowledge of the survival of the First Peoples of Canada.

Although much has been written about the history of Canada and the relationship of governments and settlers with the First Peoples of Canada, testimony of this true history as lived by the First Peoples of Canada has been brief.

As former students, now adults, we are Survivors of the infamous Indian residential schools system. Our testimony, shared at our reunions, is shared here as remembrances and reclamation of our lived experiences.

Yet the history of the Assiniboia Indian Residential School has been an enigma, a unique story left untold. Its existence and operation, from 1958 to 1973, were almost unknown to residents of the City of Winnipeg, including those living in River Heights, the neighbourhood where this Indian school was situated. What story was never told? Did you see us?

The history of Assiniboia includes close to 1,000 individual stories, the lived experiences of former students, staff, parents, River Heights residents, and many others in the First Nations and non-Indigenous communities of Winnipeg and Manitoba. This book offers a small selection of these stories. More are left to be told.

The survivors of Assiniboia have deliberately included the word “Indian” in this book, to describe not only a school, but more importantly, the intent of an Indian school: to make Indian children ashamed of who we were, and to force us to abandon our First Nations identity. We sanitize or minimize the reality of what an Indian residential school was when the word “Indian” is avoided in an effort to evoke an acceptable concept of residential schools, also known as boarding schools, usually reserved for the elite in society.

Through relentless efforts to assimilate the original people of this land, we have at various times been called Indians, Natives, half-breeds, Métis, Aboriginal, Indigenous, and First Nations. Society is generally more comfortable with these words that try to erase the derogatory connotations of terminology used in the heyday of colonization, including “Indian.”

To be clear, our identities arise from thousands of years of nation building, from which our birthright is to proudly self-identify in this region as Anishinaabe, Cree, Dakota, Dene or Anishininewuk. Across Turtle Island, there are countless First Nations, each with its distinct identity, history, and heritage.

The transfer of Indian children from different Indian residential schools on Manitoba Indian reserves was part of an overall plan by the Government of Canada to implement a further step in the ongoing attempt to assimilate Indians. The institutionalization of Indian children, begun in 1831, was formalized in 1920 by Canada’s Parliament with the legislated mandatory removal of children from their families. These children were locked up in Indian residential schools operated across Canada.

The Indian residential school policy and era were not intended to support or educate our people, but to get us out of the way of settler development and access to the wealth of Canada’s natural resources. Implementation of the policy, primarily carried out by churches acting for the Canadian government, aimed to displace our Nations, destroy our traditional ways of life, our customs, cultural and linguistic heritage, legal rights, spirituality, and governmental and societal structures, and the very identities of the Indigenous Peoples of Canada. Canada’s residential schools policy targeted children to ensure continuous destruction of our First Nations identity from one generation to the next.

Assiniboia was the first Indian residential school to provide high-school education in a major urban environment in Manitoba. Each of us had attended Indian residential schools from about the ages of six or seven, with schools situated both on Indian reserves and in rural and northern Manitoba communities. At first we thought that being transferred to Assiniboia was just another step in the progression of our incarceration. Yet, the Assiniboia Indian Residential School, by design or inadvertently, was a place where students began to peek out of a dark place and realize that we could live amongst the colonizers and attain some measure of adaptation to our changed lives.

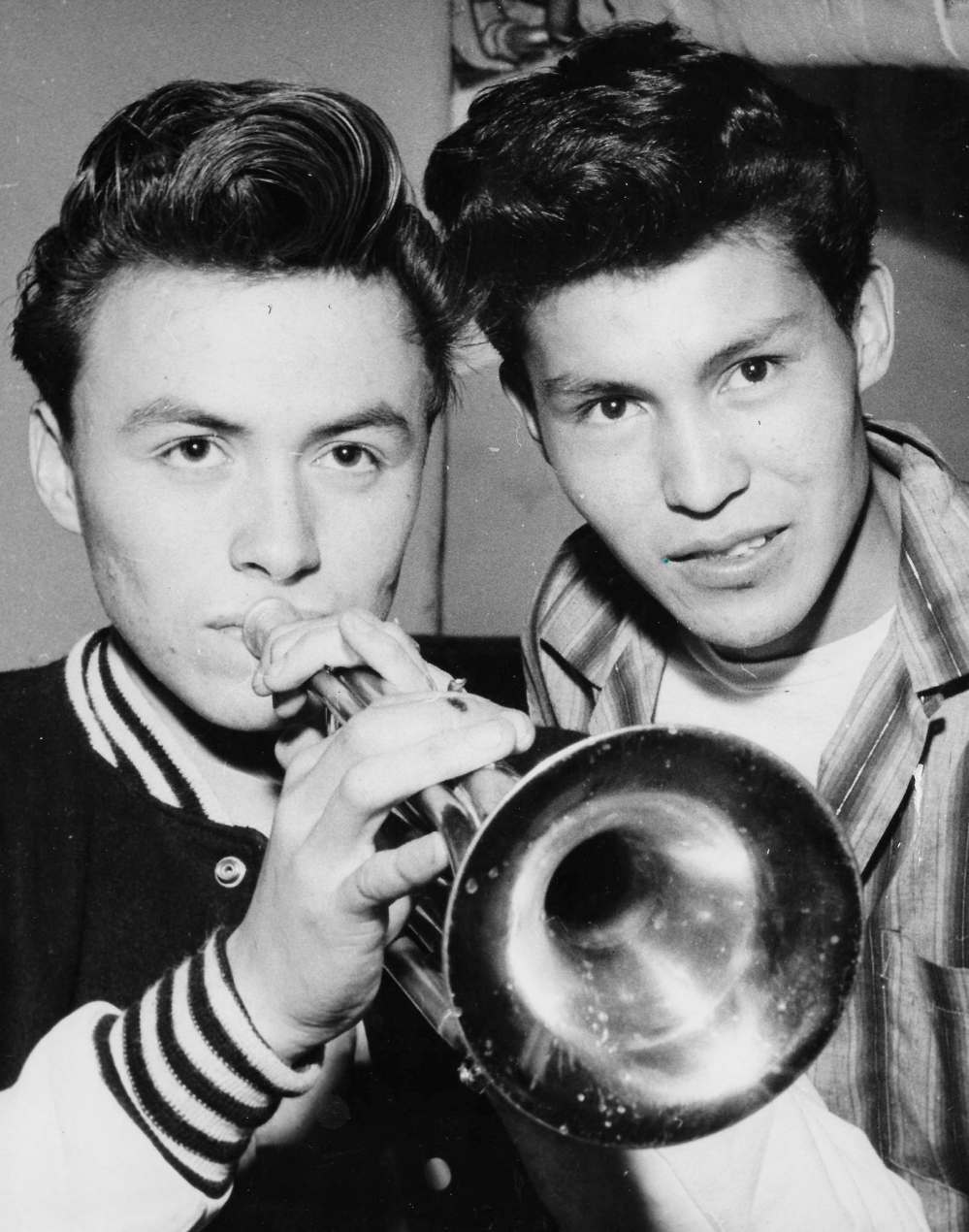

Our stories began to weave together at Assiniboia. Now a little older, and having been away from our families and homes for so many years already, we began to emerge as friends and something like family. Our new reality included some freedoms and some amenities. With plenty of good food to eat, we began to reclaim our individual identities and to emerge as young First Nations adults. We began to find our voices, our laughter, and to value our relationships.

We were slowly introduced to a larger urban society and its amenities, including social, arts, and sports events. Within a few years, these new realities were further enhanced and we began to experience some freedom from the perils and trauma of incarceration in our previous residential school captivity.

As Assiniboia progressed over the years, students did not have to be at the facility full-time. Assiniboia slowly transformed into a hostel, with older Indian youth transferred in from residential schools in other provinces. Given nutritious lunch bags, they began to be bused to various high schools around the city, including those within the River Heights community.

Many Assiniboia students went on to higher education, often later in life. Those from the earliest years wished that the positive adaptations to life at Assiniboia had been their experience. Sadly, many were so damaged by their early childhood incarceration that their lives were lost early in adulthood.

Assiniboia was an unprecedented success in providing a sensible and successful model, accomplishing to some extent the government’s policy of assimilation by influencing the transition of Indian youth to urban living and white societal “norms.” Yet, even then, and throughout our lives, we never gave up our First Nations heritage and identity. Most of us have worked hard to reclaim our identity, culture, language, family, and community.

The legacy of Assiniboia is the blending of stories not only of Survivors, but also of many in the community. This includes the residents of River Heights, who lived along the same roads and streets as Assiniboia with their children, yet didn’t know who we were or why we were there.

Theodore Fontaine is the author of Canadian national bestseller, Broken Circle: The Dark Legacy of Indian Residential Schools, A Memoir.