Lies lead to truly terrific treatise

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/01/2019 (2477 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Shakespeare famously remarked on “how this world is given to lying.”

To which, in her captivating exploration of liars and those suckered in by them, American journalist and author Abby Ellin says amen.

There’s no condescension on offer here for the gullible and conned — precisely because Ellin counts herself among the victims.

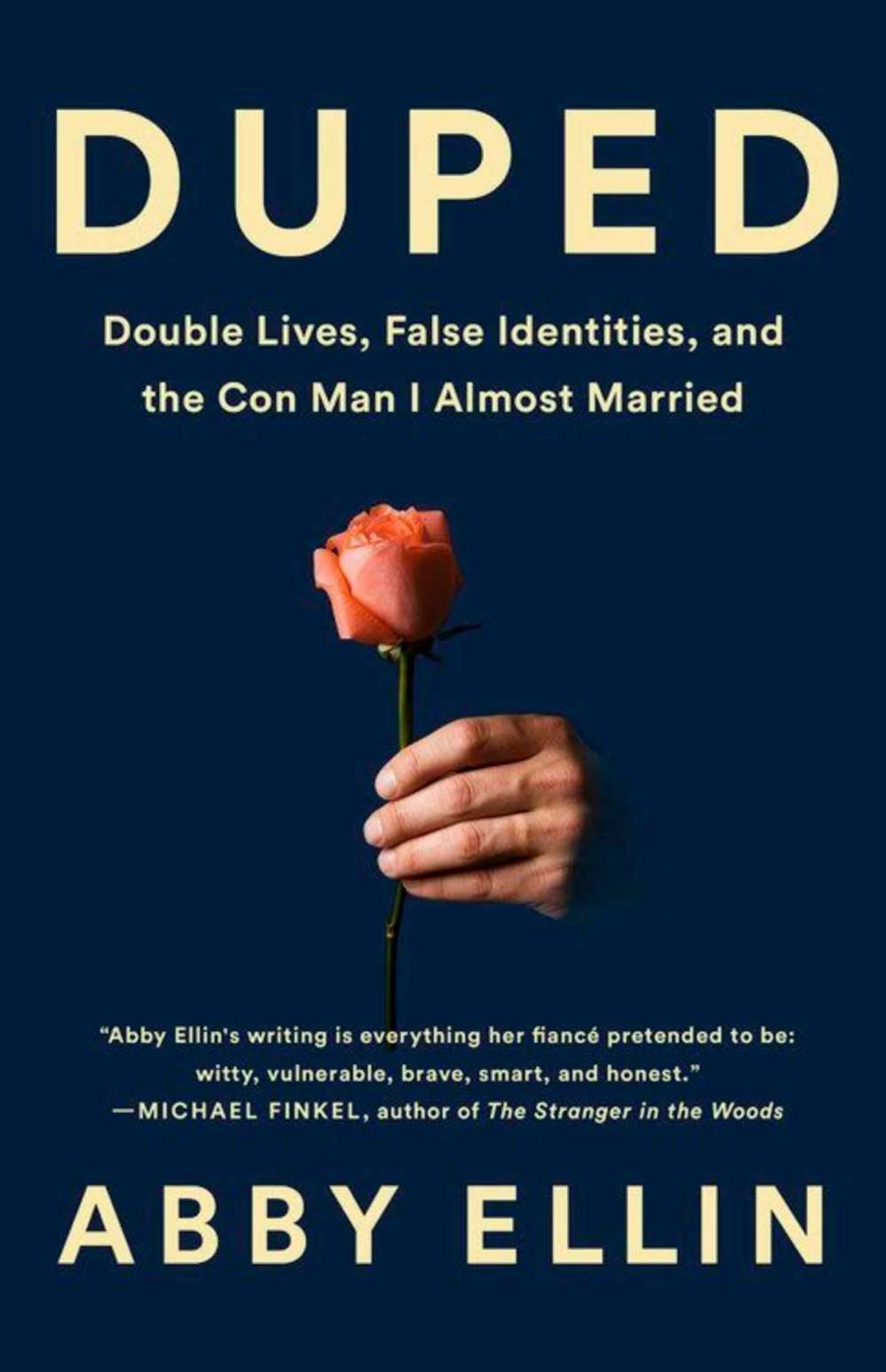

In an astonishingly intimate opening chapter of Duped, she chronicles her courtship by (and engagement to) her very own prince of deceit — a guy she calls the “Commander.”

The Commander was a bona fide doctor, but that was about the only bona fide thing about him. He regaled Ellin with tales of espionage missions to Iraq and Afghanistan, a stint as medical director of Guantanamo Bay prison and a 20-minute special audience he enjoyed with Barack Obama.

She believed in him and his cloak-and-dagger escapades, to the point of accepting his marriage proposal.

But the tangled web of lies he wove eventually blew apart, leaving her sorely doubting her own smarts.

She’s plain-spoken about her credulity. And she displays a self-deprecating and ironic wit, even as she re-traces her benighted infatuation with the Commander.

Ultimately, his lies gifted her this book. Her attempt to come to grips with them was the genesis of her investigations here, and led her to research the scientific how and why of duplicity, in part as a self-help remedy.

Along the way she considers who’s most likely to lie, why men and women lie differently, the neuroscience of lying, techniques for successful lying (and successful detection of lying), why polygraphs (a.k.a. “lie detectors”) aren’t reliable and whistleblower legislation.

Seemingly, in human relations, others are often never really knowable. And sometimes those others don’t even much know themselves — which is precisely why they make such good liars, often half-believing their own lies… Ellin’s Commander being a case in point.

She views “the discovery that you’ve been exploited” as “so deeply bewildering, unsettling and hurtful that it constitutes real trauma,” akin to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). She even comes up with a new clinical term to describe the syndrome of those duped by a loved or trusted one: post-deception stress disorder (PDSD).

Her research is prodigious and impressive, and the writing nicely paced. There’s a lot of pep in her prose, resulting in a book that’s both playful and learned.

But for all her research and reflection, the brutal truth about Ellin is that, after being suckered by the Commander, she was subsequently lured into a similar, albeit briefer, liaison with a married man who was happily cohabiting with his wife (he told Ellin he was separated), and whom she dubs the “Cliché.” He also had a mistress on the side (apart from Ellin herself). Even she can’t believe her idiocy.

Still, Ellin remains a gamer. One moment she avows she’s “quite content since opting out of romance; a huge chunk of me isn’t interested in that nonsense.” But in the next sentence she backtracks: “And yet — that nonsense makes the world go round.”

Apparently common treachery can’t keep an uncommon woman down. Or impair her writing.

Douglas J. Johnston is a Winnipeg lawyer and writer.