Inuit oral histories pointed to Franklin wreckage — but no one listened

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/01/2016 (3661 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

If ego were a parade in Canada’s Arctic, a white man would probably lead it.

For it could well be that the Inuit in Canada’s North got a raw deal and should get more credit for helping to locate the bones of one of the world’s most famous ships — Sir John Franklin’s Erebus — in her underwater grave in 2014.

Author David Pelly says information passed down by the Inuit in the late 1800s defined where the ship was (although searchers argue it was technology that pinpointed its exact location).

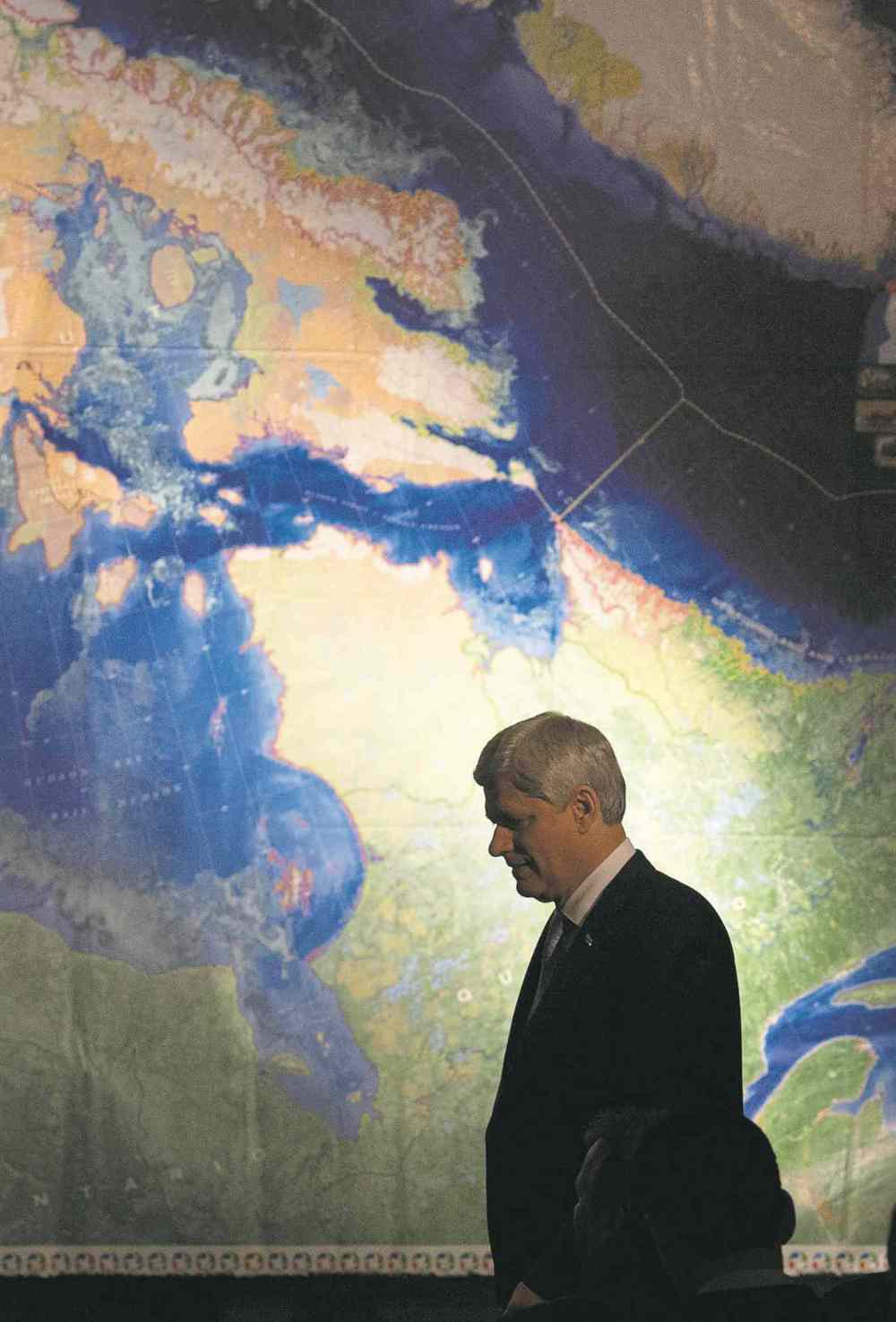

Either way, while Canada’s Inuit unquestionably helped solve one of the greatest exploratory mysteries of the Victorian Age, it was then-prime minister Stephen Harper who excitedly announced it to the world in 2014. While there was mention of the Inuit contribution, if any of their people were there with the beaming Harper, they were lost in a sea of white.

But what may make people such as Pelly fume more than anything is that the finding of the ship was characterized as a discovery. It wasn’t. Franklin’s sailing ship, trapped in the ice and abandoned, was discovered by the Inuit, as much as 169 years earlier.

The distinction isn’t moot because to sidestep, to mistake, to misrepresent, to ignore the history of a people who are the unquestionably respected masters and custodians of Canada’s Arctic is to inch toward cultural genocide. At the very least, it is insulting and demeaning.

Franklin’s sailing ship and everybody aboard it vanished around 1845 on a dangerous mission: to conquer the Northwest Passage sea corridor from the Atlantic to the Pacific in what was the most treacherous, ice-clogged body of water anywhere. It was then the biggest maritime prize in the world.

Although not the theme of his latest book, Pelly describes in Ukkusiksalik some of the information in Inuit oral histories that were like bread crumbs on the ice leading to what is left of HMS Erebus.

In a chapter on Franklin, Inuit elder Tuinnaq Kanayuk Bruce repeats information passed down to her orally about how Inuit helped a U.S. 3rd cavalry officer and his men hunt for the explorers from 1878-80.

The cavalry party was informed by an Inuk, Ikinilik, that he had visited a ship frozen in the ice but there was no sign of life, and when they got inside there was a corpse in a bunk as well as canned meat, forks, knives and spoons. Inuit also said they had to walk out five kilometres from the shore on smooth ice to reach the abandoned ship.

Another man, Puhtoorak, said he visited the ship multiple times at Ootgoolik. That name corresponds to the area in which Erebus was found. (The ship later sank.)

More importantly, a New York journalist with the cavalry searchers reported he had learned (obviously from Inuit) that the ship was near an island named Keeweewoo, a small island near O’Reilly Island, which, author Pelly says, “as far as we know, corresponds very closely with the location of the shipwreck found in 2014.”

Says a critical Pelly: “It is evident that this long-standing Inuit oral testimony pointed quite accurately to the ultimate modern ‘discovery’ of the Erebus shipwreck.”

Franklin and his 129 men all died in the expedition; The Erebus’ sister ship, Terror, is still missing.

A sizeable portion of Pelly’s book is the oral histories of Inuit life and their experiences in the Ukkusiksalik area north-northwest of Hudson Bay, among rock 2.5 billion years old.

Inuit oral storytelling is arresting. There is no embellishment, no guile, no attempt to please or persuade, deceive or distort, somewhat like a good occurrence report by police: matter-of-fact, neutral, robotic.

It takes some getting used to, but it’s worth it.

In 1969, writer Barry Craig was aboard the icebreaker that helped the first commercial vessel conquer the Northwest Passage and fulfil the dream that Franklin and his men died trying to achieve.