Martian mission marred by clumsy prose

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/12/2017 (2953 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In the last decade or less, Mars has become cool again like it hasn’t been since the mid-1950s. Former U.S. presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama both spoke of a manned mission to the Red Planet as space exploration’s next big leap, and two 2010 bipartisan policy pieces made it an official NASA goal to leave human footprints there by the 2030s. It’s an idea that is so tantalizingly close, space scientists and enthusiasts alike can taste it.

Likewise in fiction. Andy Weir’s 2011 novel The Martian is both a milestone and a new high watermark for this long-running genre: a bestseller that became a box-office juggernaut and critical darling. On the big screen, Matt Damon played the titular stranded astronaut in a near-future almost indistinguishable from today. We’ve moved beyond the fantasies of both pre-Apollo works and the sporadic B-movie treatments of the ’80s, ’90s, and 2000s.

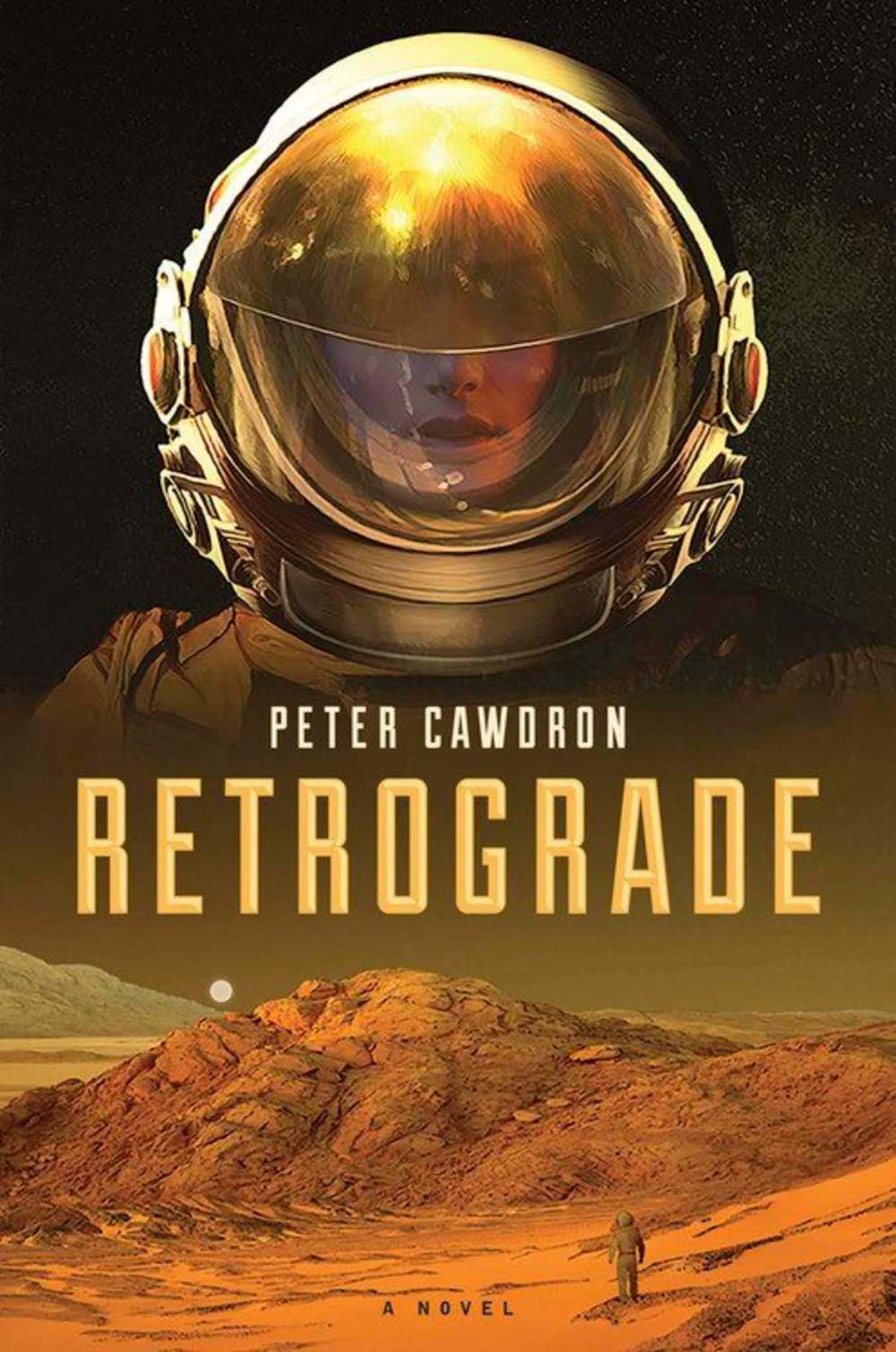

Veteran Australian novelist Peter Cawdron strives to add to this newer, more grounded period of Martian fiction — tonally similar to works such as The Martian or even Gravity, starring A-list dramatists, rather than fun and stupid romps like 2001’s Ghosts of Mars or 1990’s Total Recall, starring Ice Cube and Arnold Schwarzenegger, respectively. Has Cawdron been able to clear that bar?

Sort of. The first 50-odd pages of the novel seem in line with Weir’s debut novel in that the setting — a 10-year Martian colony staffed by scientists, engineers and technicians — suggests neither a huge leap in time nor a leap in technology, with no wacky plot twists or characters. There are four autonomous modules staffed by international space agencies from the U.S., China and Russia.

The physical, political and organizational structure mirrors the real-life International Space Station, but the twist is that this global effort becomes undermined in the first pages when nuclear war breaks out on Earth, pitting the modules against one another.

This is a great concept and, by unhappy coincidence, a topical one. The characters in Cawdron’s novel have to deal with being left alone without much support or even communication from their various mission controls because of the vagaries of orbital mechanics.

There are a number of technical details to be worked out in terms of making supplies last for an indefinitely longer period, but this setup provides the added tension and narrative layer of nations suddenly in a state of war affecting the relationships of a few dozen people representing those nations in their small, fragile scientific outpost.

Where Retrograde starts to go off the rails is in a dramatic shift in plot near the halfway point of the novel. Without giving it away, suffice to say that the twist strains credulity in both the narrative and the motivations of the characters. The out-of-nowhere reveal of a deeper and more sinister force at work below the surface of these events is likely to break the suspension of disbelief for many readers.

In fact, the story is still reasonably compelling, but it’s a jarring shift for the reader. Story structure is a problem on the smaller scale as well, with an overuse of character-development flashbacks that kill the momentum of the scenes they were inserted into and feel shoehorned in.

Cawdron does a lot of things right, including a clever basic story concept, some decent character development and a solid technical grounding. The missed opportunity is that if the overall story logic were more cohesive and the unfolding of the narrative more organic, the result might have reached beyond the level of a decent beach read.

Joel Boyce is a Winnipeg writer and educator.