Outrage over B.C.’s ‘Highway of Tears’ inspires novel rich with fantasy, realism

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/03/2014 (4308 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

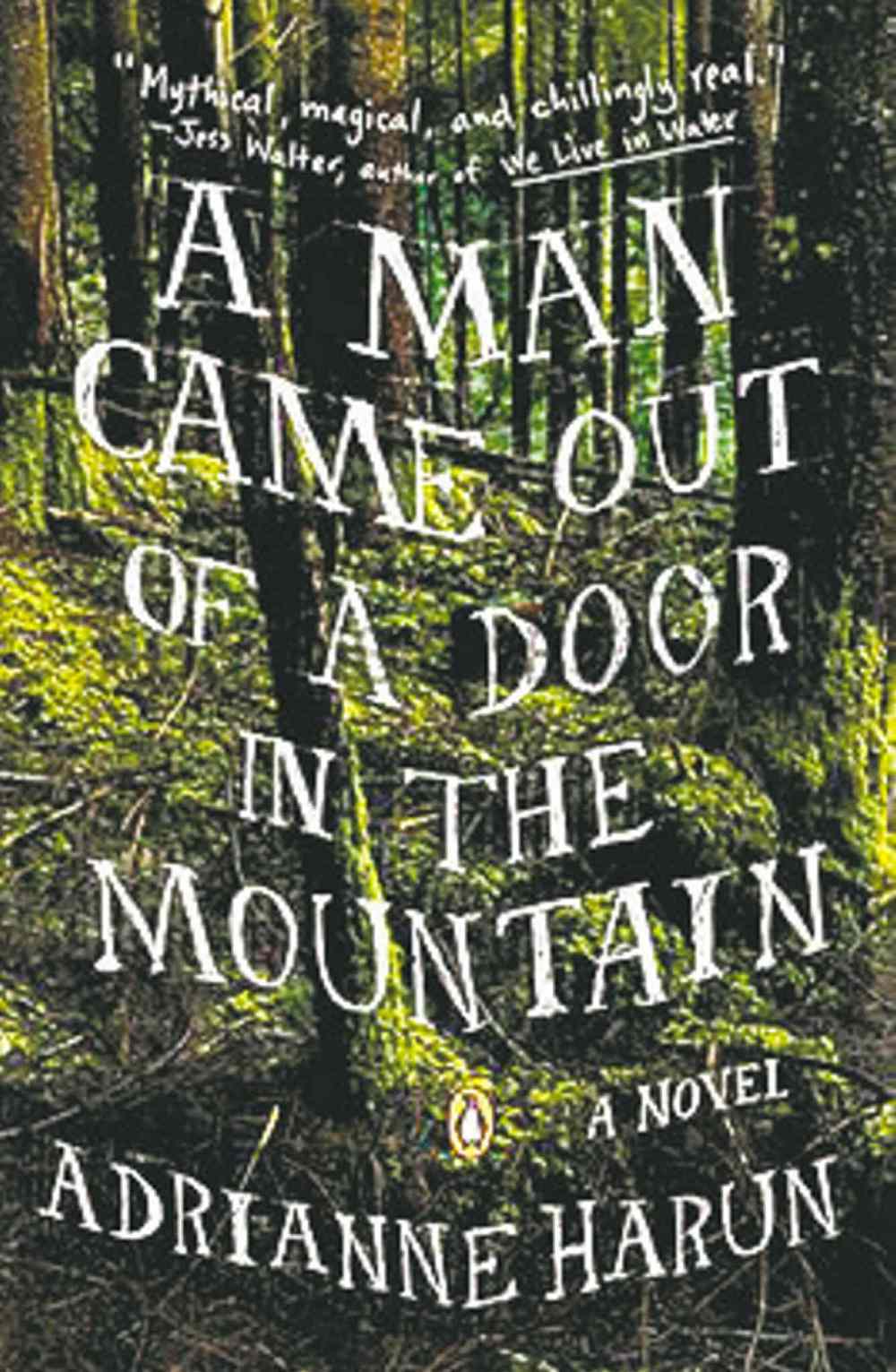

To live up to a title like A Man Came Out of a Door in the Mountain, a novel should incorporate fairy tales, vivid portrayals of good and evil, even a moral.

This book, difficult to categorize but intriguing to read, does all that and more.

Its great success, though, is its constantly favouring a rich blend of the fantastic and the realistic over the didactic, a remarkable achievement for a book that was conceived in anger over the tragedy of missing and murdered Canadian women.

Adrianne Harun, a writer, editor and teacher living in the state of Washington, has published many short stories and essays; this is her first novel.

“The story here was sparked by outrage over the ongoing murders and disappearance of aboriginal women along Highway 16, the so-called Highway of Tears, in northern British Columbia, a situation that needs as much light as can be shined upon it — and energy and solutions,” she says in the book’s acknowledgements.

The story “veered into a more fanciful narrative” after a dinner-party discussion of good and evil, Harun reports.

The result, a seamless weave of fantasy and gut-wrenching realism, does indeed shine such a light without veering into an essay, an editorial or a poster, although all of those forms are legitimate responses to these outrageous attacks on women.

The main narrator is “thick-skulled Leo,” a teenager with his head in the clouds. He and a handful of “oddball friends” pass their summer vacation in the usual pursuits of a small-resource town — falling in love, driving around in decrepit vehicles and visiting the town dump to shoot at crows and rats. Some of their vehicles possess “damaged souls of their own.”

In this unnamed town these teens follow their parents and other relatives into sordid encounters and menial jobs at the Peak and Pine Motel.

The manager of this establishment has made his private peace with his guests and their ceaseless card games. “And as long as he caught the games before they soured, before cheating was discerned and called out and denied, before drunken men fell off their chairs and spattered dignities and empty wallets and spilled booze demanded loud retribution that would, if left unchecked, culminate in wall-battering, furniture-smashing fights — well, everything would be all right.”

The town and its environs are also home to a repulsive brew of child abusers, crystal-meth makers and moonshiners.

Then there’s the devil, occasionally spotted and often speculated on. He gets his due in short chapters bearing such titles as Devils Make the Best Salesmen, Laundry Day for the Devil and Beauty + Despair: A Poem by the Devil.

In this hellhole, what better escape can Leo indulge in than stories?

“Almost everybody who shows up here has a story, usually embellished and smoothed out. That’s one big difference right off between those who arrive and those who live here. Our own stories were unedited — sprawling and unpretty — and nothing could clip and shape and redefine them as long as we stayed here. As long as we were alive.”

Even one of the low-lifes invents a story, trying to twist his lust for a girl he has kidnapped into a vision of heaven: “Pearly gates held tight by thunderbolts, pompous know-it-all guards, scads of rules.”

Fortunately, A Man Came Out of a Door in the Mountain breaks all the rules.

Anything can happen in a novel in which a mountainside has a soul.

Duncan McMonagle teaches journalism at Red River College.

History

Updated on Saturday, March 22, 2014 8:23 AM CDT: Tweaks formatting.