Recasting Riel

Historian claims Métis leader's role, significance has been misinterpreted

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/02/2020 (2106 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Rebellion, resistance. Prophet, madman. Militarism, nation building. European, Indigenous. Colonizer, colonized. Such are the contradictions and dichotomies which surface when historians (and armchair historians) discuss the significance of perhaps the most controversial player in Canadian history: Louis Riel.

For almost 150 years, Canadians have debated how to qualify the Métis leader’s impact on Confederation, on Canada and on a path forward toward reconciliation.

And according to historian M. Max Hamon, most historians — Alexander Ross, Tom Flanagan, Maggie Siggins, and even graphic novelist Chester Brown — have misinterpreted the historical significance and the causes and consequences associated with the Red River Resistance.

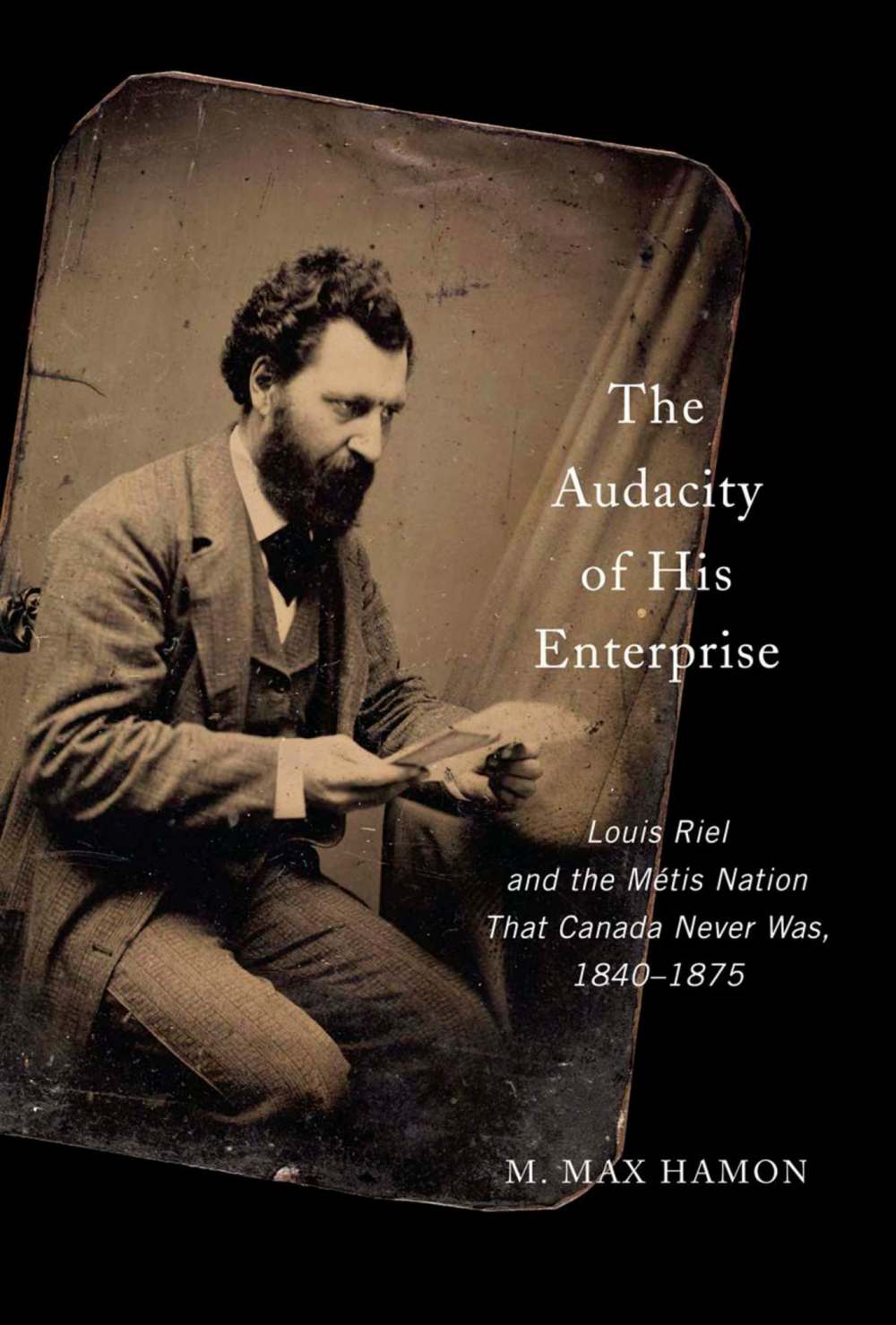

In The Audacity of His Enterprise: Louis Riel and the Métis Nation That Canada Never Was, 1840-1875, Hamon, a McGill and Queen’s University scholar, attempts to debunk the traditional trajectories historians, such as the ones listed above (and even the likes of Desmond Moton), have made about Riel.

Hamon makes a two-front argument that suggests that Riel’s quest was less about resistance and more, as he would say, about nation building. And in doing so, Riel was able to dance in both Western and Indigenous spheres. More to the point, Hamon argues vehemently that “there was a moment in the negotiation for Confederation when public opinion was informed by ideas of indigenous rights.” And despite the decades of subsequent oppression, “alternative versions of Confederation were proposed, and it is up to us to recover those alternatives.” This seems to be hyper-relevant in 2020, as 20th-century versions of Canada seem to be à la mode.

Through new archival research and the re-examination of past archival work, Hamon counters some of the assumptions of prior popular histories and challenges the problematic “depictions of physical force in the ‘Red River Resistance’” (Hamon’s quotes) which “continue to dominate historical explanations.” In this history, Riel’s impact and significance are presented less as the troubled youth who returns to Red River following failed schooling and love, picks up the Métis cause, takes over Fort Garry, leads a provisional government and somehow becomes a father of Confederation.

Rather, Hamon argues a more nuanced progression. It begins with Riel’s matriarchal upbringing, his intense education in Montreal and his unique ability to interweave the world views of British, American, and Métis voices in Red River, and leads to the final negotiations that saw the postage stamp version of Manitoba enter Confederation — conceived and calculated by Riel.

Hamon purposely keeps the scope tight, limiting his examination to 1840 to 1875. In doing so, he hopes to avoid the pitfalls of lumping all of Riel’s experiences into the the final few months of his life (which ended in November 1885), which can mislead the reader of history and suggest that all of Riel’s life was marred by mental illness, delusion and melancholic demise. Hamon counters by suggesting that “choosing to end the story in 1875 challenges the narrative of tragedy.”

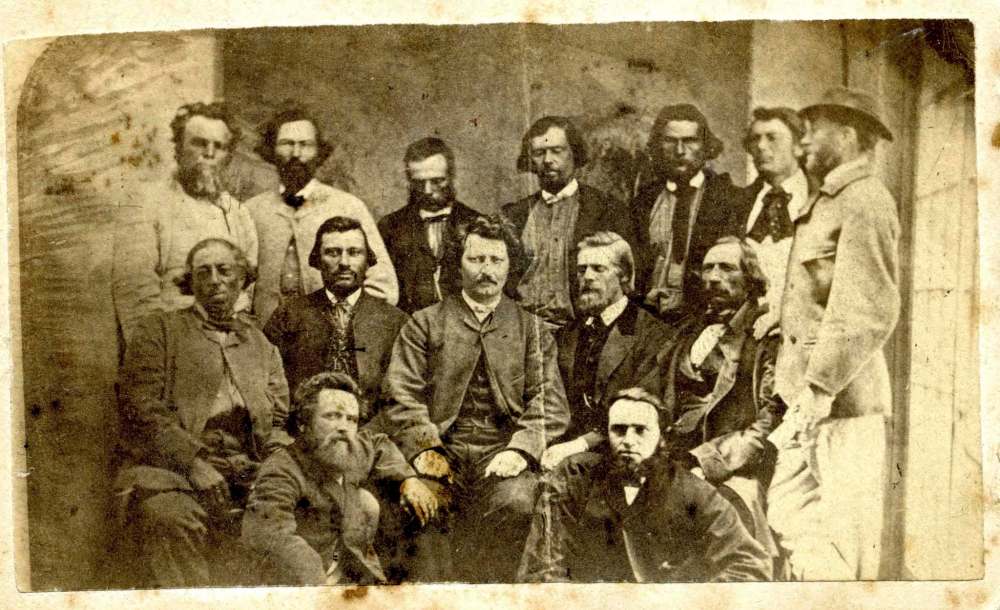

In stark contrast, despite Hamon’s agreement that the killing of Thomas Scott — whose namesake Orange temple in Winnipeg has finally collapsed — signed Riel’s death sentence, he posits that “Riel was chosen to lead not because of his military reputation but for his ideas and ability to persuade.” By this, Riel was more adept with political and cultural tools, rather than those of violence and sheer resistance. He sought to engage in the exercise of inclusion and nation building, as evidenced by the very makeup of the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia.

What is problematic about Hamon’s work, however, is the less nuanced teasing out of who had and has claims to indigeneity. Almost forgotten in his text are the voices of the Anishinaabe, the Cree and the Dakota. These are cracks and fissures that reveal themselves today.

But despite the modest acknowledgment of this complexity, Hamon does well and with much depth to place a historical spotlight on the brief moment where some Indigenous voices were heard — serving as lessons, perhaps, “to teach us about the incompleteness of settler sovereignty.”

And Canada continues to learn this the hard way, one land grab and resistance at a time.

Matt Henderson is assistant superintendant at Seven Oaks School Division.