Reconciliation reconsidered

Artists take on issues affecting indigenous peoples in emotional collaborations

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/07/2015 (3790 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The timing of this enormously significant and inspiring volume couldn’t be more fortunate: The closing event of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), a little over a month ago, has ignited a national dialogue about the vital next steps our country must take to forge a new relationship between indigenous and non-indigenous Canadians.

Yet the artists and writers represented in The Land We Are have crafted a disruptive, thought-provoking challenge to this dialogue, warning that too much of it has been top-down, deliberately limited and oriented to soothing Canadians and “moving on from this sad chapter” — as if it were in fact behind us.

This mainstream version of “reconciliation,” they argue, puts the onus on aboriginal Canadians to forgive, rather than on governments to substantively redress the loss of both land rights and indigenous forms of governance. Without these forms of restitution, “reconciliation” can only mean aboriginal peoples reconciling themselves to the permanence of the colonial Canadian state.

Resistance against these narratives both fuels and informs the contributions to this book. The artistic and literary offerings in The Land We Are — many the result of collaborations between indigenous and non-indigenous artists and scholars — originated in response to the commissioning of reconciliation-oriented public art on the part of municipalities, provinces, and even the TRC itself — commissions which, according to editors Gabrielle Hill and Sophie McCall, have explicitly excluded issues of land rights and governance.

The editors are representative of the cross-cultural fertilizations characterizing the book. Hill is a Vancouver-based Métis artist with many gallery showings to her credit, while McCall, an associate professor of English at Simon Fraser University, has authored, edited and co-edited several books related to indigenous literatures, including another forthcoming collaboration with Hill entitled Stories Are All That We Are.

This beautifully produced, richly illustrated volume from Winnipeg’s ARP Books not only offers readers a visual journey into the featured artistic installations and performance pieces, but through its creative use of text and graphic design is itself an artistic statement on reconciliation.

The Land We Are is organized into four sections. The first critiques public art incorporating First Nations’ artistic traditions for being co-opted by gentrified urban developments, and offers radical alternatives that reclaim public spaces for indigenous peoples. Part 2 textually deconstructs and re-interprets the official apologies of both Prime Minister Stephen Harper and President Barack Obama, the latter of which is barely known, having been unceremoniously buried in defence appropriations legislation.

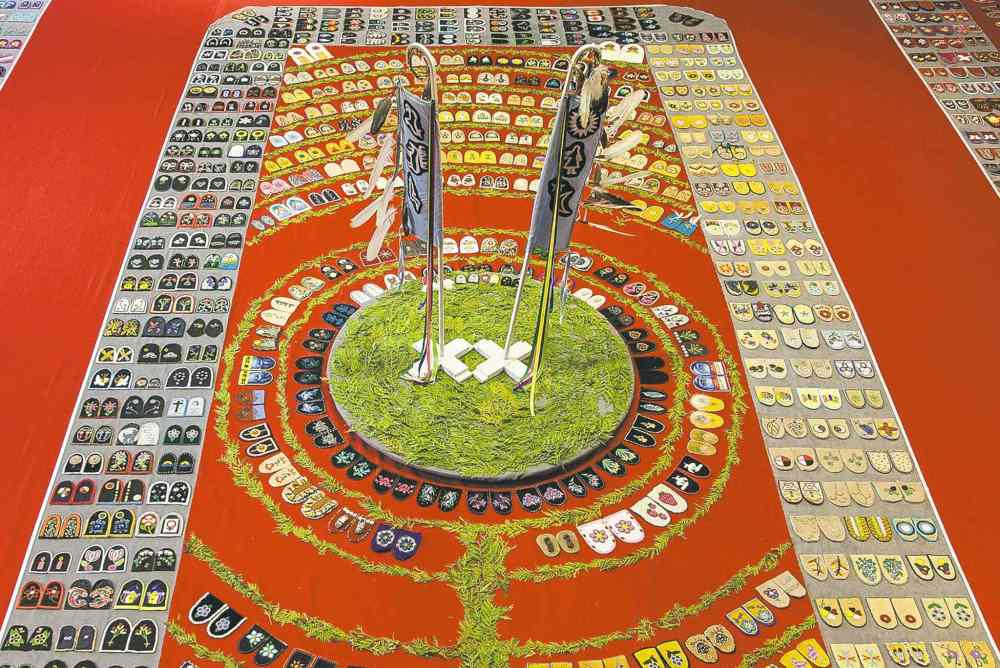

In Part 3, powerful collaborative practices are featured. They include Walking With Our Sisters, which commemorates the memory of North America’s missing and murdered indigenous women though hand-sewn vamps (moccasin tops) representing each woman, and (official denial) trade value in progress, which features Hudson’s Bay blankets decorated with dozens of hand-stitched expressions of outrage in response to Harper’s notorious assertion at the 2009 G20 meeting that Canada had “no history of colonialism.”

Part 4 contemplates the transformative and insurgent power of art and performance — a power which can be decidedly personal and intimate. We learn of Tsimshian/Cree performance artist Skeena Reece’s ritual bathing of photographer Sandra Semchuk, while their dialogue about the piece is transformed through preserved tracked changes and comments from editors McCall and Hill. In Hair, communications scholar Ayumi Goto and artist Peter Morin (Tahltan) transform their own bodies — Goto by cutting her long hair (evoking the shearing of Native children in residential schools) and Morin by weighing himself down with 28 rocks tied to his body, symbolizing the traumatic experience of the schools.

The book concludes with an essay by settler scholars Allison Hargreaves and David Jefferess, reminding fellow non-indigenous Canadians of their responsibility to un-learn the comforting narratives that have normalized and made invisible the colonialism from which they have for so long benefitted and to listen to, learn from and collaborate with indigenous artists, scholars and activists.

The Land We Are makes clear that genuine reconciliation will require specific and difficult work from non-indigenous Canadians. Significantly, this is work with which a grassroots group of Winnipeggers have already engaged. Their freshly launched website, groundworkforchange.org, provides settler Canadians an easy-to-use portal into decolonization principles and indigenous issues.

Far from “putting this sad chapter behind us,” The Land We Are is a profound argument for considering the process of reconciliation as “always beginning” — one that can only be measured through a transformed relationship between Canada’s peoples.

Michael Dudley is the indigenous and urban services librarian at the University of Winnipeg.