Repulsive reprobate

Death row con man hoodwinked publisher, conservative writer to take up his cause

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/03/2022 (1314 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

This is a story of wrongful exoneration — the misbegotten freeing of a murderous psychopath who, released from prison, nearly killed again.

Or, as author Sarah Weinman frames it, a tale of “wrongful conviction in reverse.”

Her 2018 book The Real Lolita gained some notoriety, both popular and highbrow literary. It credited the real-life 1948 kidnapping of an 11-year-old Camden, N.J. girl as inspiration for Russian-American writer Vladimir Nabokov’s classic 1955 novel Lolita.

In Scoundrel, she’s again tapped into the intersection of crime and matters literary.

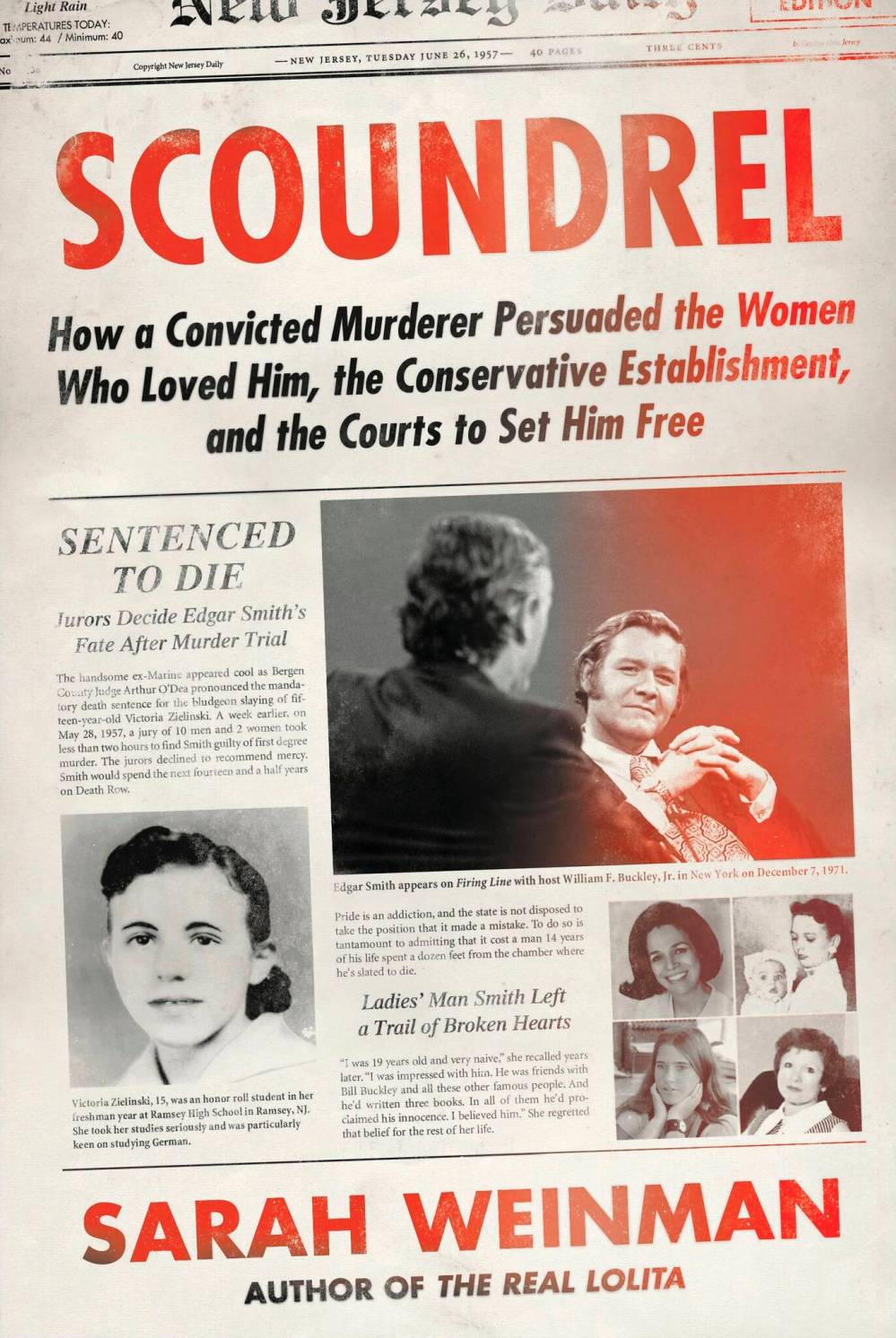

In 1957, a New Jersey jury convicted 23-year-old Edgar Smith of the murder of 15-year-old Vickie Zielinski. The prosecution’s evidence was so overwhelming that the jury, skipping lunch, retired for less than two hours before returning to render a guilty verdict.

Smith was sentenced to die in the electric chair at Trenton State Prison on July 15, 1957. Sundry appeals pushed back the date of execution numerous times.

And then, enter celebrity writer and editor, National Review magazine founder and conservative icon, William F. Buckley.

Buckley befriended the death row inmate and took up the cause of his having been wrongly convicted.

He also enlisted the aid of Sophie Wilkins, an editor at prestigious American publisher Alfred A. Knopf, to secure publication of Smith’s self-serving memoir of his trial and conviction. Titled Brief Against Death, it became a bestseller.

Wilkins, a 52-year-old veteran editor, was seduced by the two-decades-younger Smith’s good looks and facility with the English language. Her initial professional editor-author letters to Smith soon morphed into mutually erotic correspondence.

Without Buckley and Wilkins’ support, Smith would never have avoided execution or have been released from prison.

The book’s first 100 pages are pretty much run-of-the-mill true-crime narrative. However, once Smith links up with Buckley, and in equal measure Wilkins, the story takes on another dimension.

Smith played Buckley and Wilkins, and played them big time.

Then again, he also played the courts, his lawyers, the media, editors, publishers, a raft of big-name American writers and a series of admiring women. Smith was one slick psychopath.

Weinman’s astute use of Smith’s elegant, witty and discerning correspondence to and from each of them is illuminating. Often appallingly so, in light of Smith’s penchant for violence and brutality that re-surfaced after his release from prison.

Five years after his exit from death row he nearly stabbed to death a woman — a complete stranger — in a botched robbery attempt.

He then fled hither and yon across the United States. He was ultimately arrested, tried for and convicted of attempted murder, kidnapping to commit robbery, assault with a weapon and attempted robbery. Sentenced to life in prison, he died, still incarcerated, in March 2017.

Neither Buckley nor Wilkins ever escaped the legacy of their alliance with Smith. And nor, to their respective credits, did either ever seek to minimize or deny the extent of their assisting his duplicity.

Weinman has done a fine job of casting light on a dark but fascinating bit of legal-cum-literary history.

By book’s end you’re so repelled by Smith’s brutality, lies and machinations that the only raiseable quibble is with the book’s title.

Scoundrel is too modest a pejorative for the likes of Edgar Smith.

Douglas J. Johnston is a Winnipeg lawyer and writer.