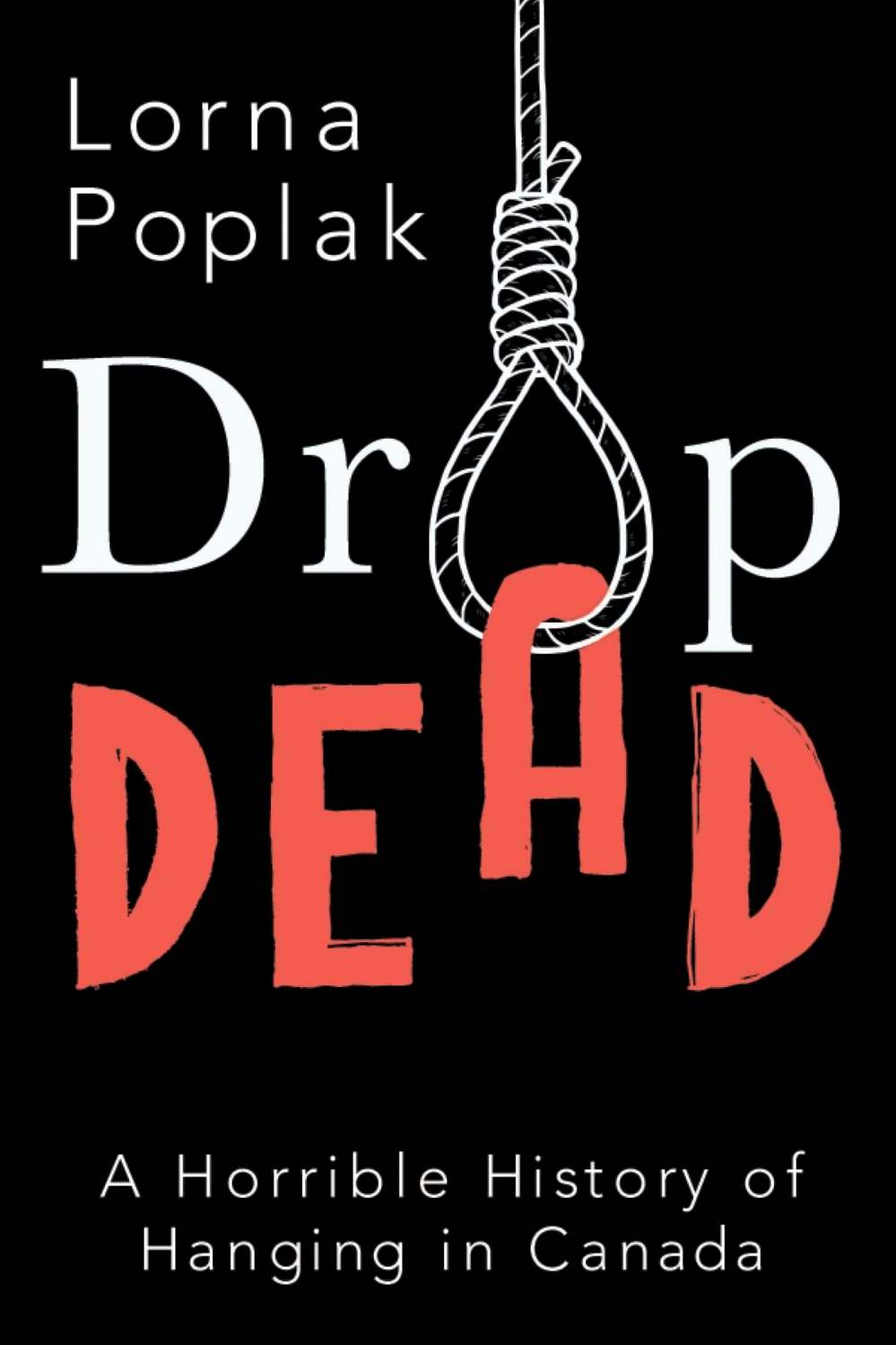

Shallow gallows

History of hanging lacks weight to tackle heavy topic

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/08/2017 (3046 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

This is an easy-to-read historical survey of execution by hanging in Canada, written in a breezy, even jaunty, style. As odd as it might sound, it’s a book about capital punishment you could easily take to the beach for a summer read.

But that lightweight quality is also its weakness.

Author Lorna Poplak is a Toronto writer and editor, and a board member of the Canadian Society of Children’s Authors, Illustrators and Performers.

And while her writing is lucid, too often her accounts of hangings don’t rise much above a regurgitated daily newspaper story.

There’s often a dearth of detail, nuance, context or analysis in her narrative. For example, the chapter devoted to female murderers, The Petticoat and the Noose, could have been enlivened by greater socio-historical insight into the status of women in Victorian- and Edwardian-era Canada. (Of the 704 people hanged in Canada, 11 were women.)

Poplak’s background as a children’s author also surfaces in small, yet annoying, ways. Near one chapter’s end, she deftly references a George Orwell quote about most people approving of capital punishment, but few wanting the job of hangman. But she then immediately follows the quotation, and closes the chapter, with a too cutesy question to readers: “Would you?”

This kind of interrogative-cum-instructional closing of a chapter may work for an adolescent audience or middle-school curriculum materials, but it’s out of place in a book intended for adult readers.

Her chapter devoted to “the end of the rope” gives a nice account of the political to-ing and fro-ing that led to Parliament’s narrow 1976 vote to end capital punishment (131 for abolition, 124 against).

It includes some adroitly chosen excerpts of speeches by John Diefenbaker, Lester Pearson and Pierre Elliott Trudeau, all three of whom opposed the death penalty.

One of the book’s better stories is about Diefenbaker recounting his role as criminal defence counsel in a 1930 Prince Albert, Sask., murder trial. His client was convicted at trial, all appeals were dismissed and the man went to the gallows.

Six months later, the prosecution’s star witness recanted his testimony, and admitted he himself had committed the murder and fabricated the case against Diefenbaker’s client.

As a result, Diefenbaker became a lifelong opponent of the death penalty, and during his term as prime minister (1957-1963) commuted 52 of 66 death sentences imposed by the courts to life imprisonment. One of those commutations was granted to a 14-year-old Clinton, Ont. schoolboy named Steven Truscott.

However, conspicuously absent from Poplak’s account of the movement to abolish capital punishment is mention of the pivotal role of the Canadian Bar Association and late and legendary Winnipeg criminal defence counsel Harry Walsh.

Walsh was co-chair of the Committee for the Abolition of Capital Punishment in Canada, and instrumental in the Canadian Bar Association’s 1975 plenary session passage of a resolution to abolish capital punishment. A year later, Parliament voted to abolish capital punishment (except for certain military offences, which lost capital-crime status in 1998).

Drop Dead is an engaging popular history of hangings, hangmen and capital crime, writ light. But a tad too light, both in the writing and the research.

An ostensibly dark history of a brutal mode of lawful execution merits more depth, and more gravity.

Douglas J. Johnston is a Winnipeg lawyer and writer.