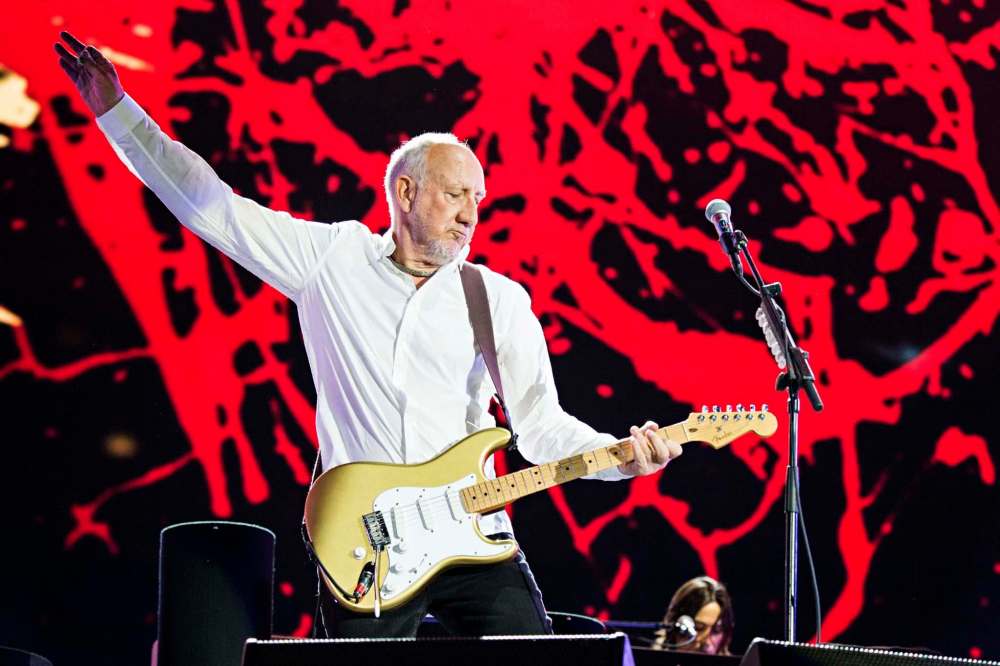

Talkin’ ’bout his generation

Townshend's debut novel draws plenty of parallels to guitarist's rock 'n' roll lifestyle

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/12/2019 (2187 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Here’s the funny thing: Pete Townshend was born in 1945, the last year of the Silent Generation. In spite of that technicality, this not-so-silent British guitarist indulges in an awful lot of “OK, Boomer” moments in his first novel — attitudes that seem tone deaf from the point of view of any culture that has paid attention to #MeToo.

Judging from his debut novel, Townshend (best known as the guitarist and principal songwriter for the Who) hasn’t evolved from the notion that male rock musicians are handsome gods who deserve to be surrounded by lusty female devotees much younger and prettier than themselves. The narrator feels compelled to describe every woman in The Age of Anxiety in terms of how attractive they are and how watching them from behind makes him feel lascivious.

Once in a while, Townshend tries to insert a female character’s perspective, but mostly, readers witness a story through the eyes of someone who sees the women around him as “a blur of feminine intoxication.”

Sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll: these are elements of Townshend’s life, as we know from his 2012 autobiography Who I Am — so it should come as no surprise that in his first novel, he writes what he knows.

The author might argue that his narrator is the fictional art dealer Louis Doxtader, not the real-life Pete Townshend. Doxtader does make a point of introducing himself to the reader repeatedly, but as American journalist Donald Murray famously said, “all writing is autobiographical.”

Townshend acknowledges the connection between fact and fiction: one of the band members has a big nose (as does the author), another hardly ever speaks (the Who’s bass guitar player John Entwistle was known as “the Quiet One”), a lead singer in the book bears a striking resemblance to Roger Daltrey and he stars in a film that sounds an awful lot like Tommy. Also, there’s the thorny issue of selling song rights to the American auto industry. Sounds familiar.

The arc of the story follows the narrator’s nephew, Walter Karel Watts, who puts away his harmonica, stops singing and steps away from the success of a pub rock band. Walter allows Ford to use the song Freedom on the Road. The parallel to real life here is that GMC commercials started playing the Who’s 1982 song Eminence Front in 2015.

The story proceeds with Walter marrying for a second time, immersing himself in gardening for 15 years, then emerging with a music project designed to satisfy his artistic yearnings and blow everyone away. Walter’s great opus develops after writing “soundscape descriptions” that we are meant to understand are very poetic.

Music critic Robert Christgau once used the word “pomposity” to describe the Who’s rock operas; the term is appropriate to ramblings by Townshend here such as “A shining star vibrates with the sound of a vast, shimmering and dissonant choir. A newborn baby cries. Shattering glass.”

It requires frequent suspensions of disbelief, but The Age of Anxiety does succeed in keeping the reader’s interest, and there are some nicely crafted phrases. Townshend shares a sense of what it’s like to play a great show that really connects with the crowd: “The energy and tension in the audience would be released in what felt like a spiritual ascendance,” he writes, adding, “Really, you have to be a musician in a big band at a huge concert to know how that feels.”

Three takeaways the author stresses: waiting is the black art of creativity, not inspiration; getting in tune with an audience can become a kind of telepathy that affects a performer’s mental health; and that being so high on drugs that you don’t remember if you sexually assaulted someone or if it was consensual doesn’t give you a free pass.

But in the end, a reader may feel the anxiety mentioned in the title because of a tension — wanting to love a novel written by someone with a proven track record for being creative, but feeling let down by this particular effort.

John Lyttle is a Winnipeg graphic designer who never quite swallowed the premise of Pinball Wizard.