Through grandfather’s eyes

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/03/2015 (3887 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

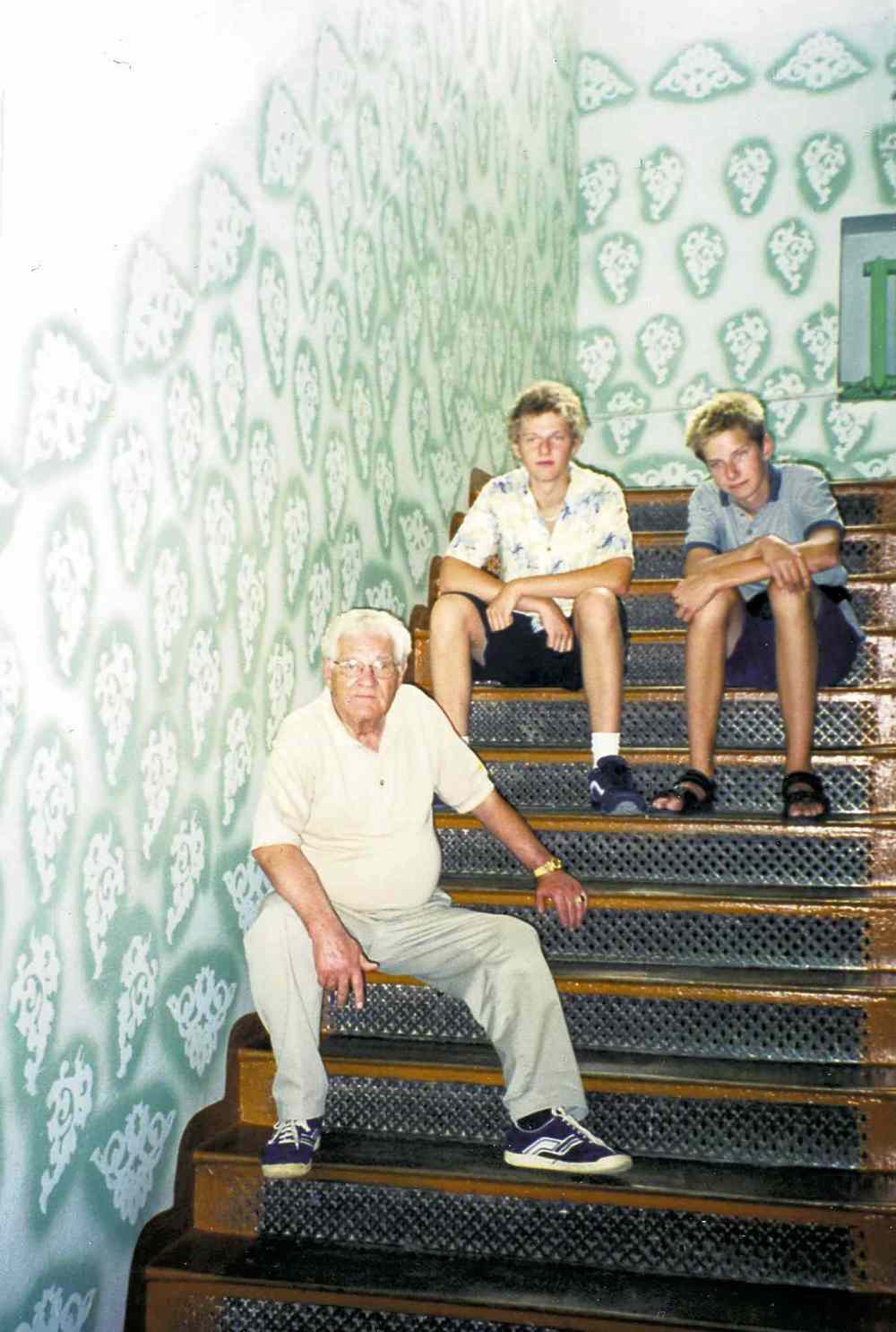

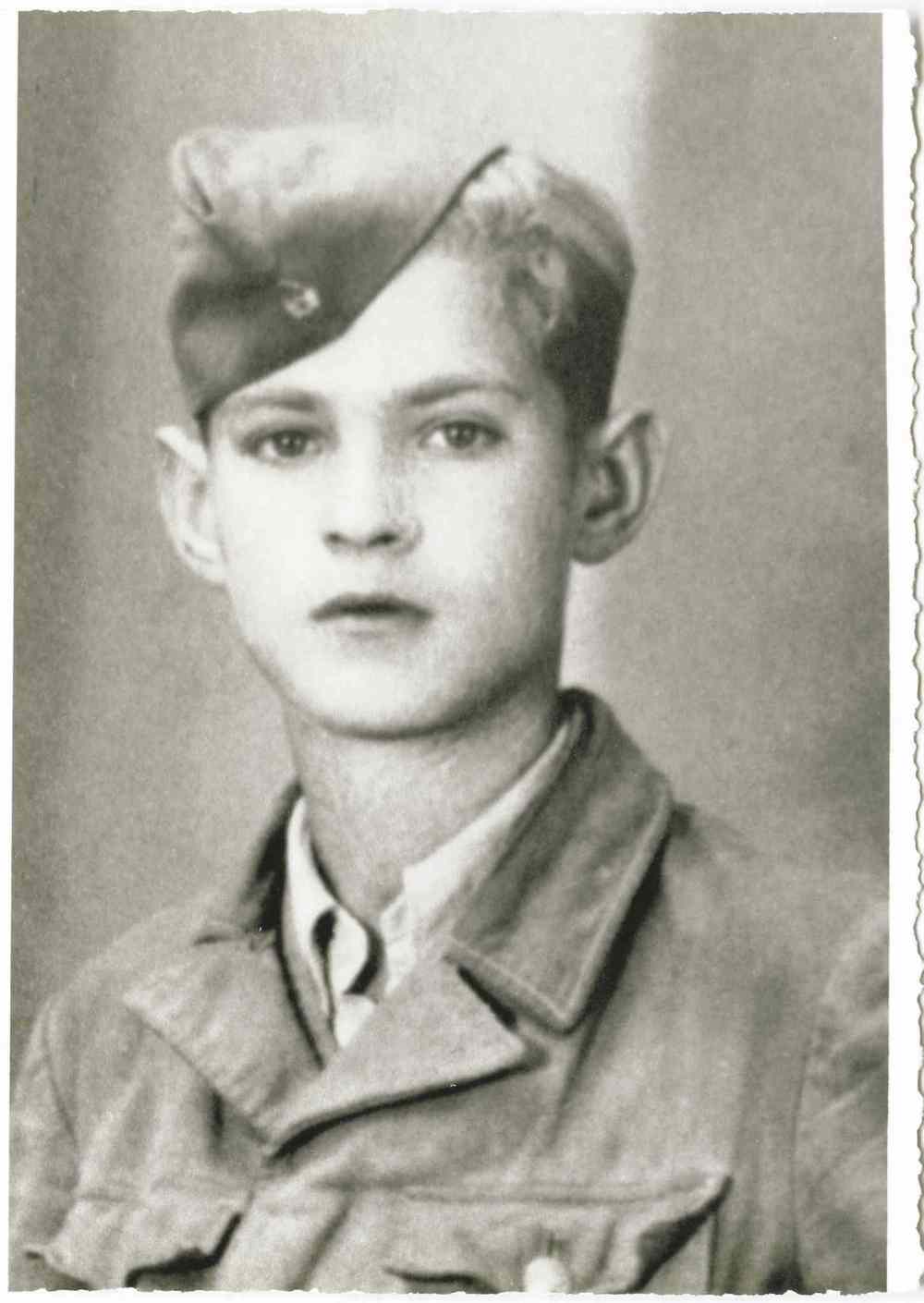

Michael Wilms spent the last 10 years chronicling the experiences of his grandfather — Harry John Giesbrecht — during the Second World War. Giesbrecht was born in Ukraine in 1928 and joined the SS in 1944. He fought for the Germans in Bastogne and the former Czechoslovakia. Giesbrecht later settled in Winnipeg, started a construction company and, during the 1980s, became the first North American entrepreneur to work in the former Soviet Union. He met with Mikhail Gorbachev on numerous occasions and even had Vladimir Putin over to his Winnipeg home for a barbecue.

The result of Wilms’ research, which included travelling to Ukraine and Europe to retrace his grandfather’s footsteps, has culminated in The Grain Fields. Wilms, 27, a second-year student in Red River College’s Creative Communications program, is launching the book on Monday at McNally Robinson, at 7 p.m.

The following is an excerpt. It’s May 2006 in Nikopol, Ukraine, and Giesbrecht is recalling the arrival of the Nazi troops to his hometown.

Together we sit on a concrete step. My Opa’s school is behind us. The pale green plaster is peeling and the dark green trim is rotted through. The two-storey school in the city centre lies vacant, collecting dust. Today, this section of the city is considered ancient and dead. The new portion of the city, the industrialized centre, is a few kilometres north of us. Large oak trees shade the steps we rest upon. My grandfather and I share a cold piva in this May heat, while we look out onto the city centre.

“How did you come to know her?” I ask, continuing our conversation.

“We went to school together. She was a year older than me and went to school in the afternoon when I went in the morning,” he says.

I know these answers, but uncovering 65-year-old facts is a process; one can’t just pull them up like a computer. It’s more like a card catalogue. One has to start at a specific topic and go through each card one at a time, until the context gets big enough that you stumble upon the piece of information you are looking for. Then you can link the story to hard facts. My Opa’s mental process is strong, but like any catalogue, there is a little dust that one has to clean off.

“You know, Mike, it was around the invasion of the Germans that she became my ‘girlfriend.'” My Opa uses his fingers as quotation marks to finish his sentence. “We were coming back from the river, I was walking her home, when we passed a gathering of people by the mayor’s office.” He points across the square in the direction of his old house. “Through a loudspeaker we could hear Stalin talking of the German Invasion and the beginning of the war.” My Opa pauses, “I guess that was May of 1941.”

“Are you sure, Opa?” I say, knowing the date is incorrect. I need him to uncover this fact so he can continue the story. “Were you still in school?” I ask.

“Oh. No, we were done school and we had been swimming in the Dnieper all day. It must have been the middle of June.”

My Opa smiles.

This realization will help him continue his story. I know the Germans launched Operation Barbarossa on June 22, 1941. Now I can date this event in my grandfather’s life and the beginning of his relationship with Tamara — hard facts.

“We just stood and listened. It was rare that we would hear Stalin speak. It was kind of exciting and adventurous.” Opa takes a swig from the bottle and passes it back to me. “When the Germans arrived some two months later, they came from that corner of the city.” Opa points to our left. “Diagonal from us, the Russian fighters had set up a machine gun that fired spurts of bullets across the square. Only two bombs were dropped on the city, one here in the centre, which was a dud, and the other exploded in the industrial section. The day they attacked, Elfrieda and I were coming back from my sister Anna’s work. Her work was located in the area the Germans were advancing from. Together, Elfrieda and I crawled across the square, avoiding the barrage of gunfire.”

The facts are endless now. I know he is remembering these events as if they are being replayed for us right in front of our eyes. I remain quiet in these situations. I just let him talk and try to record as much information as possible.

“It was something to watch the Germans marching into the city. They marched in perfect formation, black leather, knee-high boots polished and clipping on the cobblestone streets. They made quick work of the remaining Russian soldiers. I was mesmerized by their structure and order — everything for them went like clockwork. Their invasion, their occupation, everything seemed effortless. There was only one officer who accepted the Russian surrender here in Nikopol. Tamara and I watched as a line of Red Army soldiers collected. The soldiers had their rifles in hand. They stood waiting their turn to hand over their weapons. The German officer took the rifles, broke them over his knee and threw them into a pile. Then the soldiers were put into waiting trucks that took them to a concentration camp.” My Opa stops for a minute. “You know Mike, I don’t know why I found them so impressive.”

“I do, Opa. They were clean cut and polished. They were regimented, skilled, represented power and were flashy. You were 13 years old. You were a kid,” I say, trying to comfort him.

“I felt a lot older,” my Opa says. I take another swig of beer — it has lost its refreshing taste. My grandfather had been sitting up straight. Now he is hunched over.

I need to get his thoughts back to Tamara. “You dated Tamara all through this time?”

“Yes, well I wouldn’t really call it dating, Mike. I don’t think we ever kissed, let alone held hands.” He pauses. “You know, actually it was on these steps that her friend came up to me and said, ‘Harry, Tamara would like to date you.’ I stood up right then and there and said, ‘you can tell her that I accept.’ That’s how it started, Mike.” The spark that had disappeared in his eyes a moment earlier has returned.

“What did she look like?” I ask.

“Oh, Mike, she was a beauty. She was the same height as me, long blonde hair and deep blue eyes.” He pauses, “eyes so deep that when they looked at you, they looked right through you.” His voice lurches as he speaks. “She was amazing, Mike. Most of the time she was dressed like us boys, but sometimes she would wear a sundress that her mother gave her. I can still see her in my mind, Mike.”

My Opa doesn’t look at me. I smile and pat his back. I love seeing my Opa like this, it reminds me that he his human, like me. It also hurts, because I know the story that happens next and I don’t like thinking about a childhood that ended way too early. I am not ready to talk about that yet. I need to know the events in chronological order, and next is Kiev.

“Opa, did you speak German together?” I already know the answer but I need to change the subject.

“Oh no, it was always Russian. I didn’t learn German until the spring of 19-” my Opa pauses, “must have been spring of 1942.”

“Where did you learn it?” I ask.

“In Kiev, at a German boarding school the army had set up. They sent me there. There, we learned military drill, science and arithmetic, grammar, literature, and to write and speak German. It didn’t take long for me to learn the language.”

“How long were you there?” I ask.

“I was there till the end of summer,” he says.

“Were you the only one to go from Nikopol?”

“No, there were six of us, but I was the only one from our group.” Opa now gets up and we begin to stroll around the city square. The sun is now straight above us. This May heat of 45 degrees is unrelenting. I understand why, as a kid, my Opa spent all of his time at the river.

We continue walking and our conversation breaks — there is silence in the heat. We pass the mayor’s office and continue down the gravel road, leaving the city centre. We are still silent as we pass his house. We now start to follow the winding river. The tall grass blows in the light spring breeze. It does nothing to bring relief from the heat. We have left the small house behind and there is only countryside now in view. After a few minutes, we reach a bridge and I realize why we have walked this way. I don’t know if I am ready for the next story.