We can handle the truth

Books, film provide the real goods on motherhood

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/05/2018 (2800 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

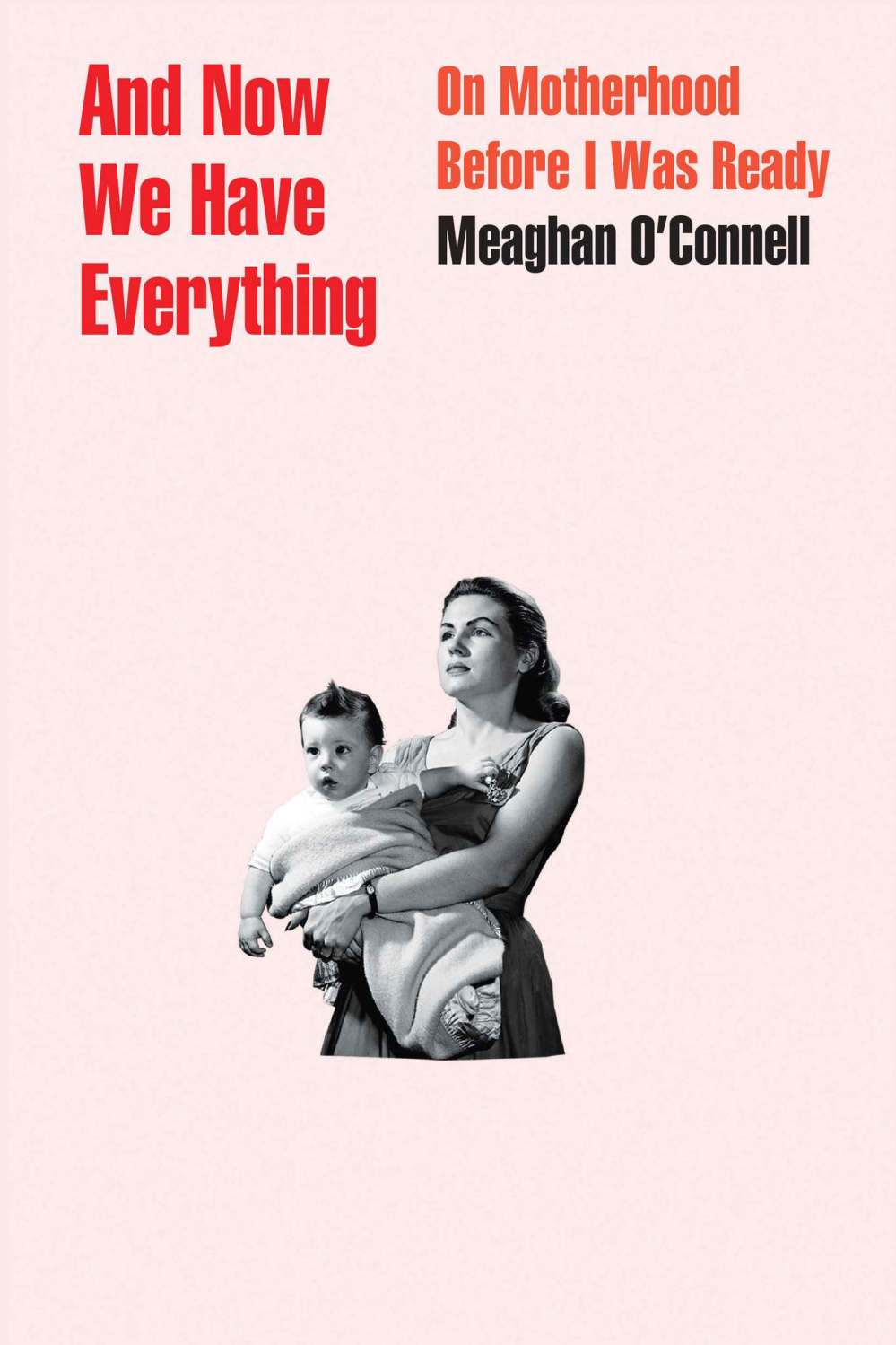

Near the end of her memoir, And Now We Have Everything: On Motherhood Before I Was Ready, Meaghan O’Connell makes an observation that could serve as a raison d’être for future art about pregnancy and motherhood.

“What if, instead of worrying about scaring pregnant women, people told them the truth?”

Released last month, O’Connell’s book (Little, Brown & Co., $34) joins a recent mini-boom of whip-smart new works that advocate for truth in motherhood. They pull back the receiving blanket on a subject that is too often swaddled in platitudes. They don’t worry about scaring women, pregnant or otherwise, and they say the things you aren’t supposed to say.

O’Connell tells the truth by offering a wry and raw look at all the private grief that comes with having a baby before you planned to, feeling alienated from your friends, your partner, your body, your self, as well as those first sleepless nights that blur into morning — “a lamp was always on” — and the waiting for things to get easier.

Screenwriter Diablo Cody tells the truth in her film Tully, which opened last weekend. Directed by Jason Reitman, Tully tells the story of Marlo (Charlize Theron), a mom struggling with the birth of her third child and postpartum depression. Marlo’s brother gifts her a night nurse named Tully (Mackenzie Davis), raising the question of help — who needs it, who gets it, and how asking for it can be unspeakably hard.

Kimberly Harrington tells the truth in her funny collection, Amateur Hour: Motherhood in Essays and Swearwords (HarperCollins, $19.99). The Vermont-based essayist presents a view from the middle years of parenting, calling BS on a culture that “superficially worships at the altar of motherhood while simultaneously not offering any genuine support or respect.”

And Sheila Heti tells the truth in her latest novel, Motherhood (Knopf Canada, $29.95). Her unnamed protagonist tries to decide whether or not to become a mother, consulting I Ching coins to help make sense of her matrix of thoughts. The Toronto-based author expertly captures the wrenching exhaustion that comes with questioning and thinking about something constantly.

As a woman of childbearing age who is wrestling with this very permanent decision herself, I devoured all of these works within the space of a week. They didn’t scare me, because I don’t believe it is a mother’s job to adopt a retail voice and sell me on motherhood. Instead, they felt like a balm.

Being this age, my age, is a trip. For the whole of my 20s, a baby was not a gift. As O’Connell writes, “A baby was the thing we were trying to keep out. A baby was a consequence.”

Then you turn 30 and suddenly someone’s aunt is smiling warmly at you at a baby shower and asking you when your turn will be, as though that’s an appropriate question to ask a stranger. “I don’t know, but I’ll be sure to get back to you re: my uterus, Carol.”

The cultural pendulum swing from “this thing will most certainly ruin your life and you should go to great lengths to avoid it at all costs” to “this thing will most certainly bring your life structure, joy and purpose, and you must vigorously pursue it at all costs,” is incredibly jarring. Clocks tick, but so do bombs. It’s hard to shake the feeling that a baby will blow up your life.

The ability to make choices and decisions when it comes to one’s fertility — indeed the whole notion of “family planning” — is actually a fairly recent development. Access to birth control ushered in a new world in which women could take control of their fertility and their lives. We have the freedom to decide when and how to have a baby. But sometimes the choice is made for us — or taken away from us, depending on your perspective — by age, socioeconomic circumstance or health status.

Still, for all our progress, there persists a stigma about women who choose not to have children, that they are somehow defective, selfish and ought to be the subject of pity or contempt. (A lot of people also seem to be concerned about who will be present at all these childless women’s deathbeds.)

Women who choose to have children are judged, too, of course. They are judged for having too many kids or too few, for being too involved or not involved enough, for working and for staying at home, for breastfeeding and bottle-feeding, for only talking about the baby and for never talking about the baby. No wonder everyone feels like they’re doing it wrong. There’s a scene in Tully in which a still-pregnant Marlo orders a decaf latte, and a stranger offers her some unsolicited commentary about trace amounts of caffeine. At the screening I attended, an entire row of women shouted, “Oh, come ON.” Judgment is a thread that runs throughout all four of these works.

With choice comes comparison, and whose choice is “better.” As the protagonist in Heti’s book says: “Other lives should be able to exist alongside our own without any threat or judgment at all.”

Judge and feel threatened we do, though. And so, we spend a lot of time and effort making choices look good, or like we’re doing OK. This is especially amplified on social media. No one wants to admit they are failing or flailing, especially in the face of so much judgment. Momming on Instagram is about documenting your life but, as Harrington poignantly observes in an essay titled Overshare, it’s also about perfoming for an audience. There is so much pressure to be perfect. Or, at least, be constantly striving for perfection.

So, when memes about the working women who bring their toddlers into Senate hearings, or Kate Middleton in her high heels hours after giving birth, are held up as examples of #havingitall and not examples of what they really are, which is lack of childcare and crushing beauty standards, everyone loses. Ditto when we qualify our experiences and fears in unhelpful “but it’s so worth it!” rhetoric.

What if, instead, we shared our fears and talked, openly and honestly, about the hard parts? Because, if these works taught me anything, it’s that so many of those fears are shared. The fear of baby-as-lobotomy, the fear of losing one’s friends, the fear of losing oneself. The fear of feeling disconnected with your body, and losing sexual intimacy with your partner. The fear of tedium, the fear of settling down. The fear of failure. The fear of regret — for having it or for not having it.

Those fears are scary to confront, to be sure. But believing you’re the only person who has those fears is scarier still.

Being a new mother is an isolating time. Tully has drawn some criticism for its portrayal of postpartum depression and postpartum psychosis, and the fact that those terms are never used and no one seems to notice what she’s going through. But as Cody told the New York Times, that was the point. “The movie is actually about her lack of treatment.” In fact, that absence of treatment is precisely what made Tully so realistic. And isn’t that a heartbreaking take-home message.

The bravery Cody, Harrington, Heti and O’Connell have displayed is not only admirable, it’s necessary. Everyone wants to feel seen and understood. By letting each other in and talking about our experiences — which are complicated, messy, and myriad — and acknowledging that there’s no right way or right choice or right life, we get closer to that goal.

The truth can be terrifying. But it can also set you free.

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.caTwitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a columnist and feature writer working in the Arts & Life department, as well as the author of the weekly newsletter NEXT. A National Newspaper Award finalist for arts and entertainment writing, Jen is a graduate of the Creative Communications program at RRC Polytech and was a music writer before joining the Free Press in 2013. Read more about Jen.

Every piece of reporting Jen produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, May 12, 2018 9:23 AM CDT: corrects book price

Updated on Saturday, May 12, 2018 9:29 AM CDT: shortens headline