Literary mystery meets dystopian future in Ian McEwan’s ‘What We Can Know’

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

LONDON (AP) — When novelists look to the future, the view is often grim. There are a lot more fictional dystopias than utopias.

Ian McEwan has good news and bad news about what lies ahead in “ What We Can Know,” a book he calls “science fiction without the science.”

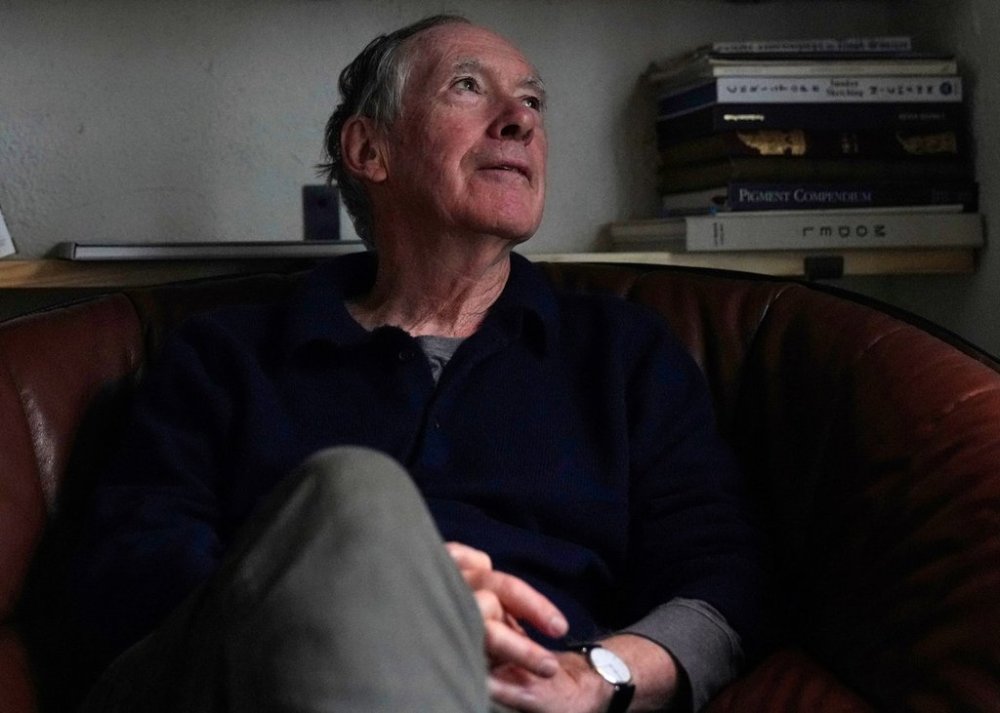

The British author’s 19th novel, published Tuesday in the U.S. by Knopf, is set in 2119 and follows a professor of literature researching a famed 21st-century poet and his circle.

So far, so cozy. But it’s a world in which nuclear war, pandemics, economic collapse and climate change — a period known as The Derangement — have halved the global population. The United States is a lawless land of feuding warlords. Nigeria is the global superpower. Inundated England has been reduced to a string of small island republics.

McEwan, 77, said that his working assumption is that humanity will “just scrape through” the next century of crises and catastrophes. The novel seeks “to look at the present through the rather envious eyes of someone in the future.”

Literary mystery

Those eyes belong to Tom Metcalfe, an English academic studying the famous (fictional) poet Francis Blundy, and a legendary lost poem that he read aloud at a dinner party in 2014.

As dystopias go, it’s a gentle one. Tom sifts through reams of 21st-century social media detritus for nuggets of information gold that may lead to the missing poem. He later undertakes an adventurous journey with touches of “Treasure Island.”

To Tom, our era is a barely imaginable time of abundance, natural diversity and human folly.

“What brilliant invention and boneheaded greed,” he says.

Readers may hear the author’s voice in the sentiment.

“There is something very reminiscent to me of the ninth century about contemporary life: passionately superstitious, even as we have extraordinary discoveries in biomedicine and in cosmology,” McEwan told The Associated Press. “At one point I describe the process of social media as if some medieval horde had run onto the wrong stage.”

Partway through the book, McEwan delivers a twist that dramatically shifts the reader’s perspective. It’s something he has done before, notably in 2001’s “Atonement” – his bestselling novel and which many think is his best.

The book’s second half delivers surprise, violence, betrayal and — another McEwan trademark — evidence of the “terrible things that perfectly ordinary people can do.”

McEwan said that he wants readers “to be, not disoriented, but just to pass through a different mirror turning the page from part one to part two.

“I hope to bring the reader back to the title.”

Not a climate change novel

McEwan says he’s not an “issues novelist,” although his books often touch on social problems and world affairs: the 2003 invasion of Iraq in “Saturday,” climate change in “Solar,” artificial intelligence in “Machines Like Me.”

In “What Can We Know,” humanity has wreaked havoc on nature. But McEwan says “this isn’t really a novel about climate change.

“The only way to write about climate change is not to,” McEwan said, as the weather outside his London home changed in an instant from sunshine to downpour. “To actually put at the center properly conceived characters and other issues and let the climate change matter simply be there as a given.

“It’s already a given. The last thing I want to do is warn people about it. No one needs any warning about it,” he said. “All that matters is your response to it.”

Upstart to elder statesman

McEwan made his name in the 1970s and ‘80s with unsettling works like “The Cement Garden” and “The Comfort of Strangers.” Today, he’s one of the United Kingdom’s most commercially and critically successful novelists, a five-time Booker Prize finalist who won the prestigious award in 1998 for “Amsterdam.” The Financial Times called him “the centrist dad of English fiction.”

He’s part of a garlanded generation of British writers that includes Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and Salman Rushdie.

“Those writers I met in the early 70s, ’80s … became lifelong friends,” he said. “That’s been a delight. And sadness as we all drop off the twig.” His friend Christopher Hitchens died in 2011, Amis in 2023.

McEwan says that he’ll keep writing “till the cogs start falling off,” and claims not to think about his legacy.

“It’s out of my hands,” he said. He recalled decades ago standing in his publisher’s office, lined with shelves of dusty novels from the 1920s and ’30s.

“And I scanned the shelves for a name I could recognize,” he said. “There were the usual dust jacket quotes: ‘Absolutely brilliant.’ ‘A novelist for our times.’ But forgotten. Just gone.”

Then there’s AI, which he thinks might write “novels of no great originality, but possibly colossal commercial success.”

And yet, he’s optimistic about the future of the novel. The reason comes back to the book’s title.

“We can’t really know the minds of people in the past,” he said. “We can’t even begin to know the minds of people in the future. We barely know the minds properly of people we’re very close to. And that’s at the heart of the paradox of why the novel is not dead: because it gives readers the illusion that they could know.

“Only in the novel can you do it.”