Tracking down the elusive spinosaurus

National Geographic Live event takes you way back, at Centennial Concert Hall this weekend

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/02/2017 (3238 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Among paleontologists such as Nizar Ibrahim, finding any evidence of the spinosaurus is like discovering the holy grail of dinosaurs.

“The story of the spinosaurus is pretty unique in paleontology because it has so much drama,” says the Chicago-based dinosaur expert, who heads a National Geographic Live multimedia presentation, Spinosaurus: Lost Creature of the Cretaceous, Sunday at 2 p.m. at the Centennial Concert Hall.

“Against all the odds we did manage to find a partial skeleton of a spinosaurus. But even that part of the story is unique, because it was a real detective story worthy of a Hollywood movie.”

Before they hunted for fossils in the Sahara Desert, Ibrahim and his team had to track down a villager in Morocco who had discovered bones that were found to be of the 15-metre long lizard.

Another part of the spinosaurus’s mystery is how few real traces of the lizard have been discovered. It doesn’t help that the biggest spinosaurus find, a partial skeleton unearthed by German paleontologist Ernst Stromer in Egypt in 1915, became history again after it was destroyed during a Second World War bombardment.

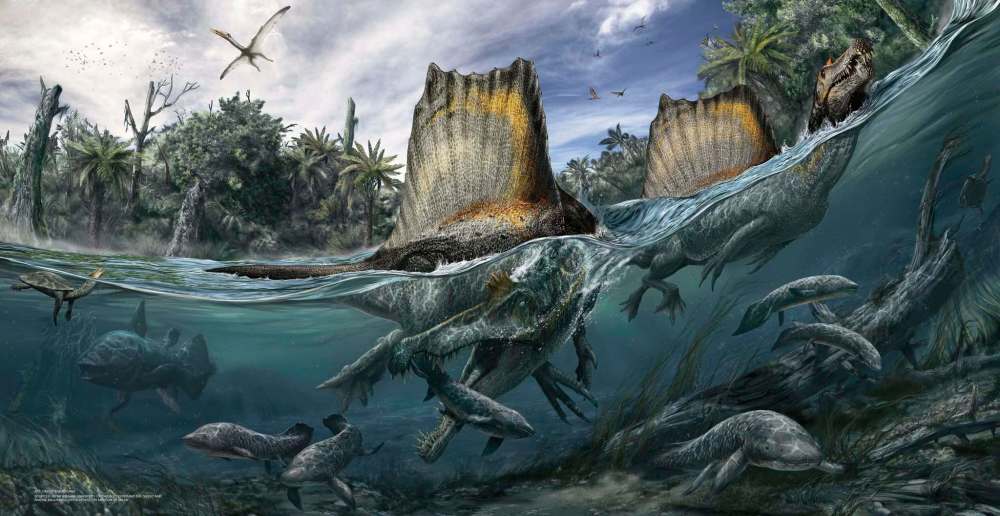

The spinosaurus — Latin for “spine lizard” — is remarkably different from the typical giant lizards such as Tyrannosaurus rex and triceratops that kids know and love. It is long and squat like a giant fish, and has giant spines almost like a fish’s dorsal fin. Ibrahim says the spinosaurus spent much of its life in the water and fed on the giant fish that existed during the Cretaceous period, about 100 million years ago.

“Spinosaurus was absent from most dinosaur books because we knew so little about it,” Ibrahim says.

“It’s a completely different kind of skeleton,” he says. “Spinosaurus has a head like a crocodile. It has a long, narrow jaw with conical teeth. Those are all adaptations we’d expect to see in an animal that predominantly feeds on fish. Sure enough, spinosaurus has all sorts of adaptations for life spent in the water.

“Could a giant dinosaur bigger than T. rex live on a diet of fish? The answer is yes.”

Just as the Prairies of Manitoba used to be a giant lake in prehistoric times, much of the Sahara during the Cretaceous period was actually a major river system teeming with life, Ibrahim says.

“You have to understand this lost world that spinosaurus lived in if you want to understand spinosaurus,” he says.

Another difference is where the spinosaurus lived. While most of the famous lizards prowled throughout North America — Alberta is one of the world’s hot spots for dinosaur fossils — there has been little exploration for fossils in Africa, where the spinosaurus lived, Ibrahim says.

“The reason why I go to this part of the world and not, say Montana or Alberta, it’s more or less virgin ground,” he says. “Africa is really severely underrepresented in paleontology, so we know very little about Africa. I’m trying to change that.”

Like so many children, Ibrahim was fascinated by dinosaurs, especially spinosaurus. His ancestry proved to be a blessing as he grew up and became a scientist wanting to learn more about the elusive beast.

“I happen to be half-German and I’m also half-Moroccan — and Morocco happens to be a country that has yielded some spinosaurus fossils, isolated teeth and jaw pieces, so I thought it might be a good place to look,” he says. “So I devoted several years of my life not just to hunt for spinosaurus, but to reconstruct the entire ecosystem that it lived in.”

Ibrahim and his team eventually tracked down the Moroccan villager who digs up fossils for a living. He took them to a spot in the Sahara that eventually led to the partial skeleton, which is the basis of the National Geographic Live presentation.

“When I started out working in the Sahara I was hoping to find a skeleton. But I wasn’t the first person to try and it is like searching for a needle in a giant desert,” Ibrahim admits.

“When I realized we had a chance of excavating a partial skeleton of spinosaurus, it was surreal, it took a long time to sink in.

“You have a lot of adrenalin when you first realize you have an opportunity to make a game-changing discovery.”

Twitter:@AlanDSmall

Alan Small

Reporter

Alan Small was a journalist at the Free Press for more than 22 years in a variety of roles, the last being a reporter in the Arts and Life section.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.