‘A terrible, lonely death’

Chanie Wenjack died fleeing a residential school for home. Can retelling his story 50 years later finally strike a chord?

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/10/2016 (3298 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

They say journalists are cynical, and in many ways that’s true. But there is an optimism in this work, too, tucked away in the space between the words we write, or the things we say. It is a hope shared by all who act as history’s recorders.

To put it another way: if we didn’t believe stories could heal, there would be no storytellers.

Gord Downie has faith in stories, too. That’s why the Tragically Hip frontman is helping put Chanie Wenjack’s story back into a national light with a new album, Secret Path. It is accompanied by a graphic novel and an animated film, which CBC will broadcast on Sunday night.

That date was not chosen at random. It will mark 50 years since Chanie died, collapsed beside the railway tracks he hoped would lead him home. At 12 years old, he was twice stolen: first by residential schools, then by the gnawing Ontario cold.

For Downie, who has been diagnosed with terminal brain cancer, showing all of Canada this story is a work of love. This is how — and what — he wants to be remembered. Telling Chanie’s story is “the best thing I’ve ever done,” he said in a clip aired on CBC last week. It helps his heart, he added.

It goes beyond just words. All the proceeds from Secret Path will go to a new project, the Gord Downie and Chanie Wenjack Fund, which pledges to promote “cross-cultural education to support healing and recovery.” This will be Downie’s legacy.

That’s how he sees it, clearly. “We’ve got to really figure out a way to help our friends up North,” Downie told CBC last week. “I’m not like, putting it all on my death. But it’s put me in a position where I can actually get some attention.”

He is not doing this work alone. Earlier this month, Downie’s friend, author Joseph Boyden (The Orenda), described how Chanie’s story united a network of artists, all of them committed to honouring Chanie’s memory through their own creative vision.

Boyden wrote a Heritage Minute and a novella, called simply Wenjack. Métis filmmaker Terrill Calder produced an animated short film. Hip-hop/electronica act A Tribe Called Red invited Boyden to deliver spoken-word pieces on their latest album.

This is what storytellers do. We raise things up to light, hoping every time that it will bring change with it, too.

Underneath all that, there’s a sadder fact. The wheel of stories just keeps churning, coming around again. Nearly 150 years into the Canadian project, we are still searching for the story that will awaken a nation to what happened on these lands.

One challenge is that the scope of colonialism is so vast. Colonialism remade an entire continent in its own image, so everything we know and learned as normal is touched by its effects: cities, forests, governments, the courts.

These dots can be connected, but the map they create is complicated. Underneath these crossing lines, the message can get obscured, or even lost. To impress a story on the widest number of people, sometimes you need a clear-cut path.

If Chanie Wenjack’s story cuts through the noise, perhaps it is because it is simple to grasp.

He was an Anishinaabe child, a small boy with a quick sense of humour. He had three little sisters, and lived a quiet life on Marten Falls First Nation.

Then he was taken from his father and placed in a residential school, where he struggled with the language. He ran away from the school, clad in only thin indoor clothes, and tried to find his way home. He died one week later in the woods, alone.

Now, as his memory is raised to national attention, it tells the story of dozens. Of the 3,201 children that are known to have died in residential schools, 194 died through suicide or accidents; 33 of those died after running away.

Will hearing their voices make a difference? Will it, as Downie hopes, spur a nation to action?

Sometimes it happens. In September 2015, the body of three-year-old Syrian refugee Alan Kurdi washed up on a Turkish beach. The image of him, lifeless in the tide, fed a worldwide wave of grief that crashed over the Canadian federal election.

But one year later, Syria is still in crisis. Refugees are still dying to find peace. Meanwhile, much of the West is embroiled in a battle with extremist nationalism that focuses much of its hate on refugee families just like Kurdi’s.

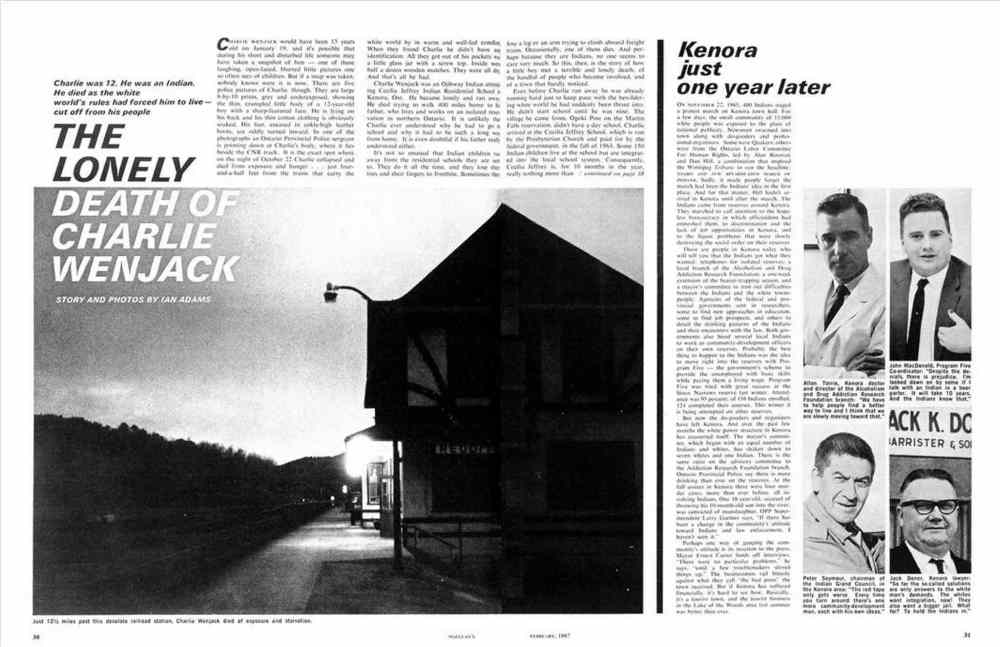

Meanwhile, Canada has gone through this cycle with Wenjack’s story already. For decades, his death haunted Canada’s self-narrative; there was an inquest. One year after Chanie died, Maclean’s ran a cover story on his death.

That is the story that Mike Downie would later show to his brother Gord and Boyden, to inspire their latest efforts.

Reading that Maclean’s story now, the most unsettling fact is just how familiar it seems. Some of the language is dated, and the last residential school closed in 1996. But the heart of the narrative could have been written last year, or last week.

“It’s not so unusual that Indian children run away from the residential schools they are sent to,” journalist Ian Adams wrote. “They lose their toes and their fingers to frostbite… And perhaps because they are Indians, no one seems to care very much.

“So this, then, is the story of how a little boy met a terrible and lonely death, of the handful of people who became involved, and of a town that hardly noticed.”

Almost 50 years later, we are still writing something very like that line. We’re still writing it about missing and murdered indigenous women. We are still writing it about clean water, and flood and fire protection, and education on First Nations.

Meanwhile, Justin Trudeau ascended to government’s top office on a pledge to mend relationships with indigenous peoples.

In September, federal lawyers went to court against First Nations over a B.C. dam project. The federal government also approved the Pacific Northwest LNG megaproject against the continuing resistance by some of the impacted First Nations.

The world into which Chanie Wenjack was born, and the one into which he fled, was one in which indigenous people’s right to exist and build autonomy in their homelands was constantly under pressure. The one we are in now is not so very different.

Maybe putting his story once again in a national spotlight will open eyes. Maybe it will spark action. I am a storyteller, and so I am an optimist. Still, we can’t forget the part that must come after the story: “It’s time to do something,” Gord Downie said.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.