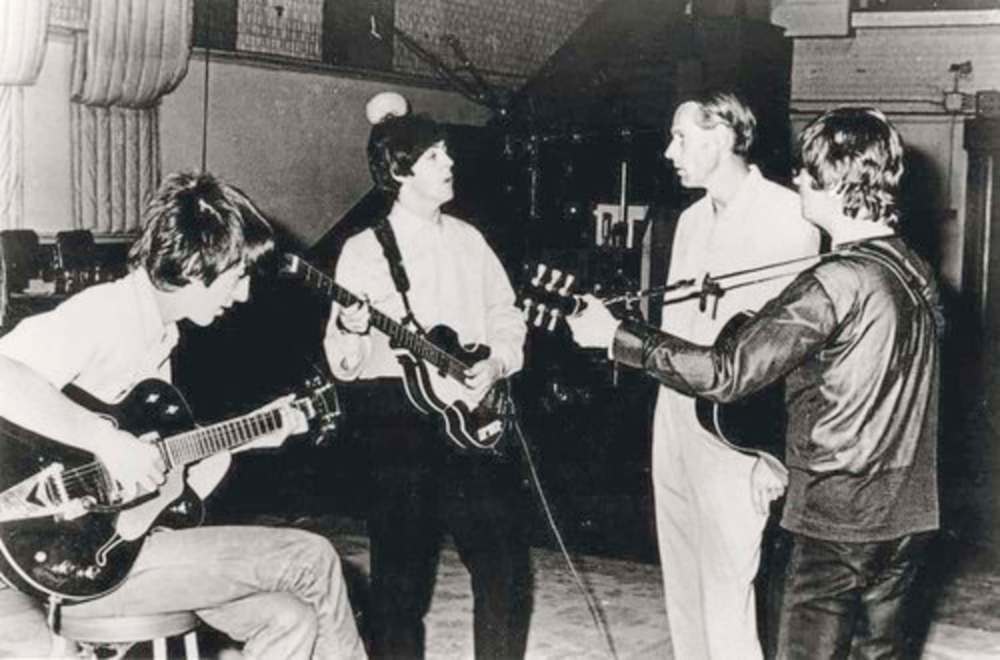

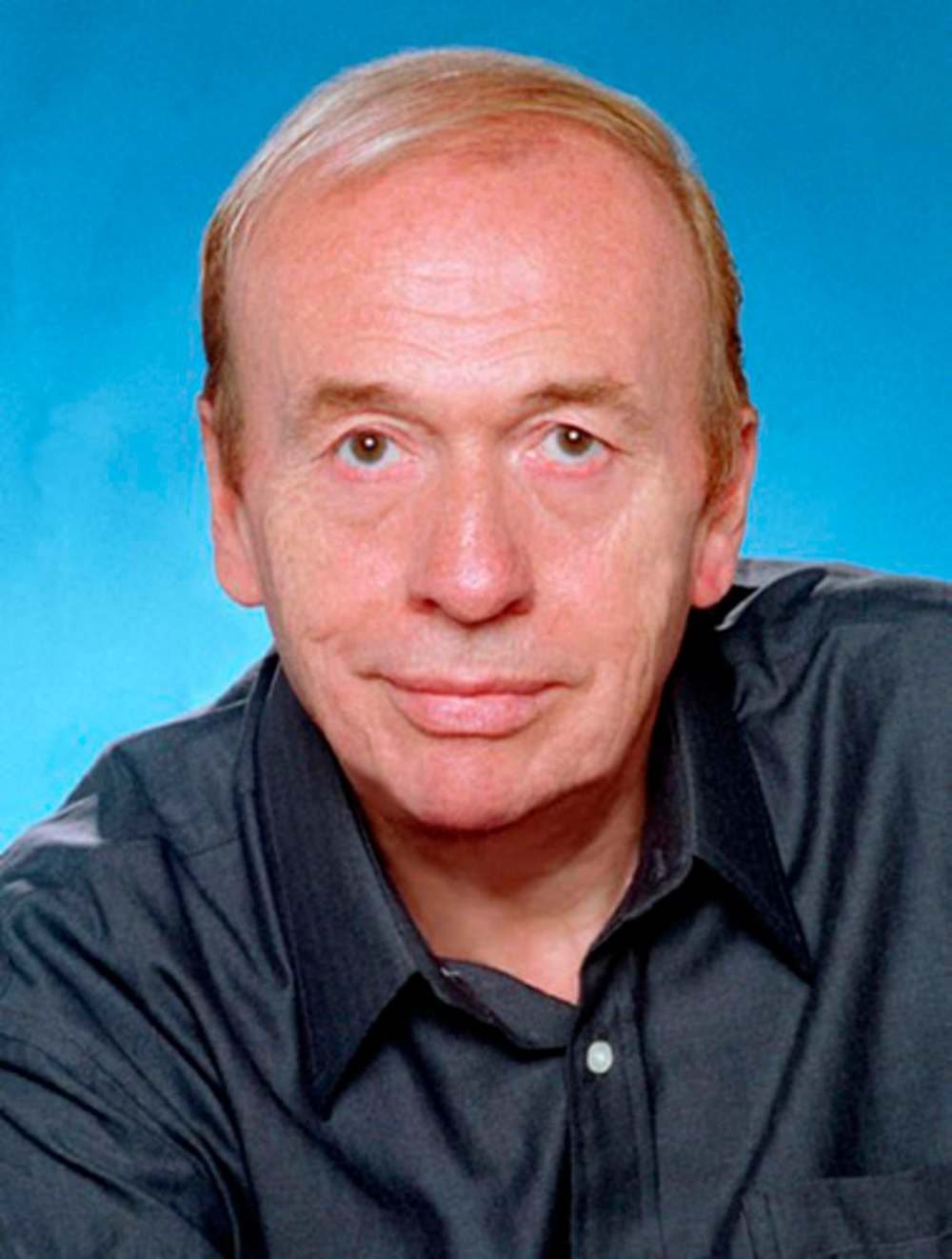

Sound engineer turned work into art form

Work with Beatles kick-started revolutionary career

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/10/2018 (2708 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

John Lennon wanted to sound like “the Dalai Lama singing from a mountaintop 25 miles away from the studio.”

Luckily, the Beatles had Geoff Emerick.

The Beatles had become a phenomenon with Rubber Soul and Meet the Beatles, crafting intricate, melodic tunes, but the Fab Four were growing creatively restless. They wanted to expand the band’s sound, to push the limit of what a song could be — so by 1966, they quit touring and focused on doing just that.

And now Lennon wanted to sound like the most important Gelug monk sitting on a mountain for the psychedelic Revolver cut Tomorrow Never Knows. In today’s world, computer programs for such sonic alteration abound — just look at the rise of Auto-Tune. But at the time, the studio itself was considered a place to record musicians, not an instrument in and of itself.

Cue Emerick. He’d come to work for famed Beatles producer George Martin when he was just 15 years old. It was the start of an illustrious career.

Emerick, who died Tuesday at 72, helped redefine what it meant to be a creative engineer shaping a band’s music from behind the scenes.

“When I was asked by George Martin, ‘Do you want to do the Beatles?’ I was just terrified, and the little eeny-meeny-miney-moe thing (in my head), it stopped on ‘Yes, I’ll do it.’… I felt really honoured to be asked,” he later told CNN.

Immediately, he was assigned Tomorrow Never Knows, which came with Lennon’s seemingly impossible request.

Nonetheless, Emerick took it to heart and began fiddling around with the equipment at Westminster’s EMI Recording Studios (later know as Abbey Road Studios).

“I was looking for something new and different all the time,” Emerick once said in an interview. “The only way that I could do that was to change the way things were done.”

“When I was asked by George Martin, ‘Do you want to do the Beatles?’ I was just terrified, and the little eeny-meeny-miney-moe thing (in my head), it stopped on ‘Yes, I’ll do it.’ — Geoff Emerick

He did a number of remarkable things on the song, including looping sounds such as a seagull squawking, a distorted recording of Paul McCartney’s laughter and a finger tracing the top of a wine glass.

Lennon’s voice, though, was its own challenge. First, he had Lennon double-track his vocals, making them sound huge and alien. Then, Emerick fed the double-tracked vocals through a rotating Leslie speaker, a speaker that was more commonly found inside a Hammond organ.

As George Martin explained in Anthology: “the speed at which it rotates can be varied according to a knob on the control. By putting his voice through that and then recording it again, you got a kind of intermittent vibrato effect, which is what we hear on Tomorrow Never Knows. I don’t think anyone had done that before. It was quite a revolutionary track for Revolver.”

Emerick put microphones closer to drums and string instruments, employed vocal distortion and even used tapes that played backward: all methods that hadn’t really been used before. To him, engineering was its own art.

“The great thing about that time,” Emerick once said, “was that the application of engineering was more artistic — working with sound was working with colours painted on a canvas.”

After his time with the Fab Four, Emerick’s career spanned decades. He continued working with McCartney and produced everyone from Art Garfunkel to Cheap Trick to Johnny Cash.

He also worked closely with Elvis Costello on many of enduring albums, including his debut, Imperial Bedroom.

On Tuesday, Costello mourned Emerick on Twitter writing, “Geoff told me once that working at Abbey Road might mean a morning recording Otto Klemperer, Judy Garland in the afternoon or the Beatles until the small hours. Nothing could confound him. How fortunate to have known and worked with him. I will miss him greatly.”

It’s true that nothing could confound Emerick. As he once said, he lived by a simple principle: “Everything was always possible. Nothing is impossible. That was always my theory.”

— Washington Post