The mother of reinvention

In a world without Madonna, would we be as obsessed over re-creating and exposing ourselves every day on Facebook and Twitter? Is the chameleonic starlet's legacy one of empowerment, or simply a generation of women who equate skimpy lingerie with self-determination?

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/09/2012 (4862 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In 1990, Camille Paglia wrote an essay for the New York Times declaring Madonna Louise Ciccone the “future of feminism.”

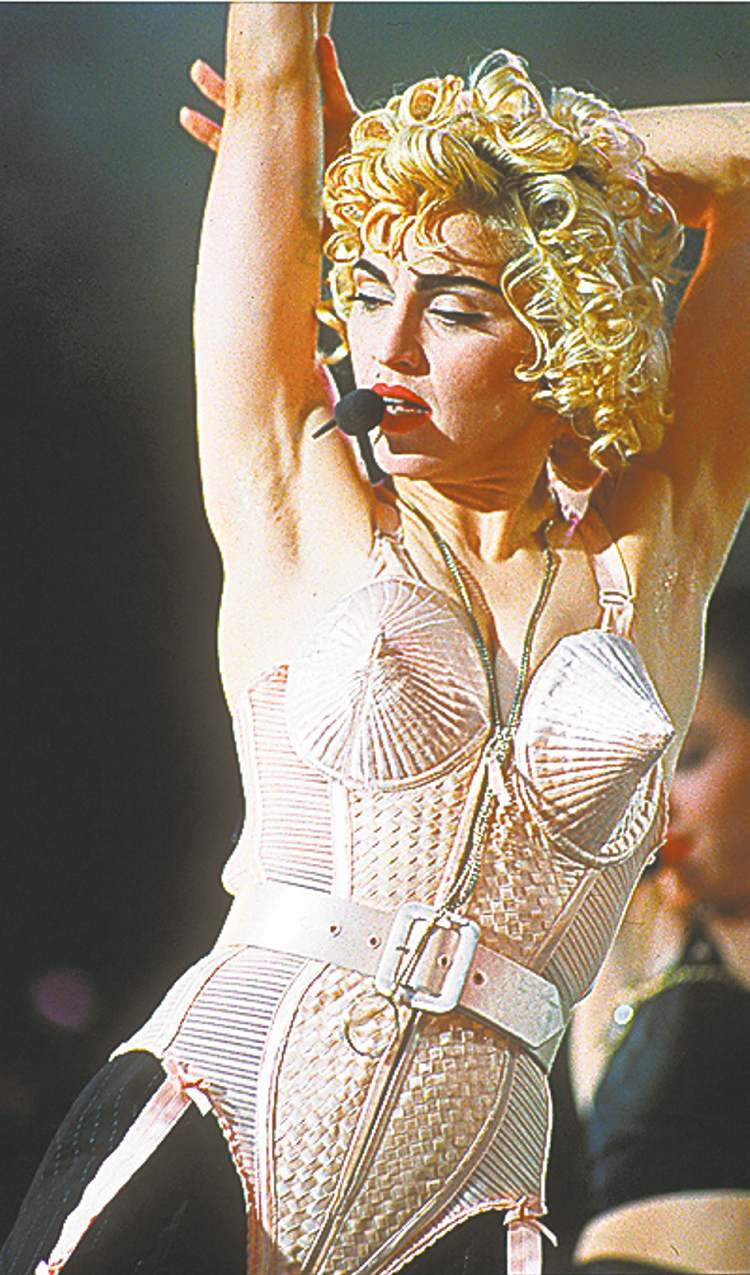

The controversial writer and cultural critic praised a pop singer known for her bullet bra and “boy toy” belt as a “true feminist.” Madonna, who was by then in a new platinum blond phase, had just released Justify My Love. In the video, the singer, clad in black bra and gartered stockings, drifts through scenarios of sex, bondage and cross-dressing.

The “future of feminism” was confusing. Wasn’t Madonna doing what women who want attention but have little power of their own have always done — take off their clothes and writhe around?

It was not confusing to Paglia.

“She exposes the puritanism and suffocating ideology of American feminism, which is stuck in an adolescent whining mode,” she wrote.

“Madonna has taught young women to be fully female and sexual while still exercising total control of their lives. She shows girls how to be attractive, sensual, energetic, ambitious, aggressive and funny — all at the same time.”

More than two decades later, an entire generation of young women has grown up in a world where skimpy lingerie can be equated with self-determination.

In a world without Madonna could there be Britney Spears, the Pussycat Dolls, Pussy Riot, Lady Gaga? Could there be entire retail empires devoted to preteen Lolitas?

Would we be as obsessed over reinventing and exposing ourselves every day on Facebook and Twitter? Would 12-year-olds dress like badly behaved adult women? Would women who are — theoretically, at least — old enough to be grandmothers dress like strumpets?

Madonna, what have you wrought? “Absolutely, she has been a big part of creating the world we live in,” says Lori Burns, a professor of music at the University of Ottawa.

“Music is a powerful cultural form. As soon as an issue is expressed through music, it has a huge cultural reach. Madonna has had a huge cultural reach.”

There are two camps on Madonna: those who see her as an empowering figure of liberated female sexuality. And those who see her as someone who promotes hypersexuality.

But it wasn’t all Madonna, says Burns. Madonna came out of a certain context — female artists such as Annie Lennox, Cindy Lauper and Pat Benatar were all questioning gender boundaries. At the same time, in the early ’80s, music videos and MTV made music a visual art form.

“She was in the right place at the right time. It was around the corner. Madonna put her particular stamp on it.”

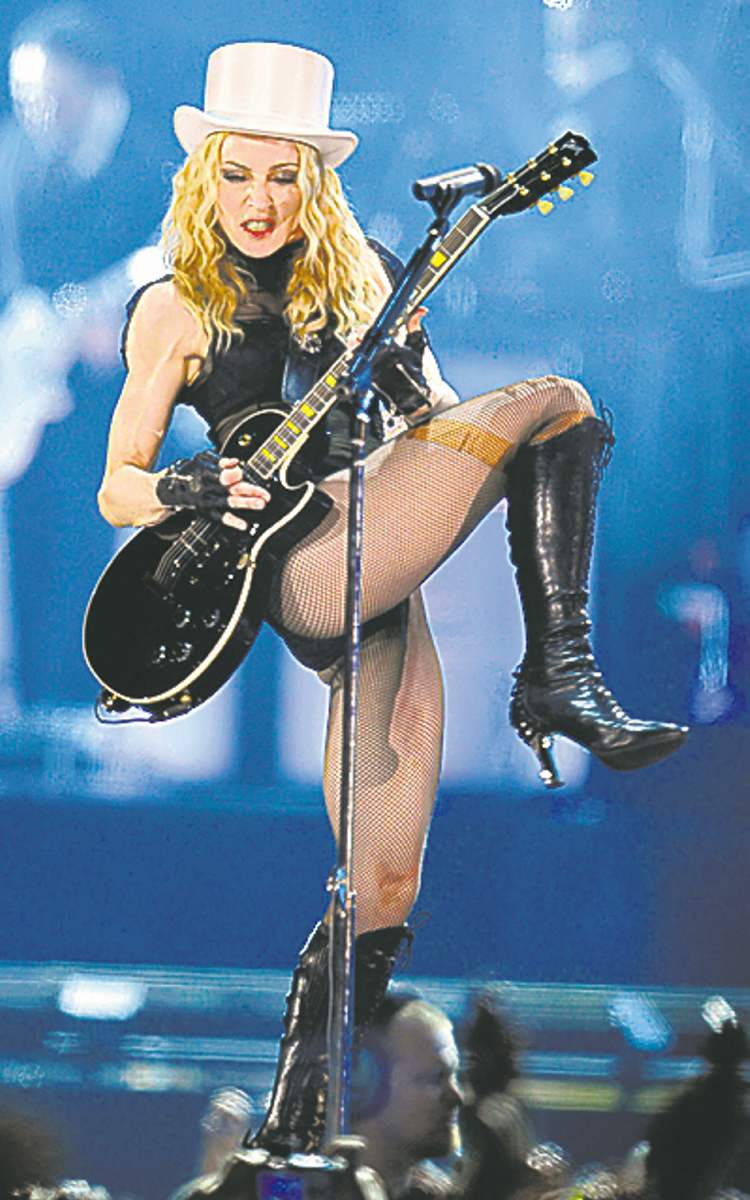

Madonna understood that image and style were integral to her work and became the top-selling female artist of the century. She re-created herself with every album.

She was nimble at incorporating new ideas and hiring people she trusted, says Burns. While Madonna was criticized as a mere chameleon or as someone who wasn’t particularly excellent at any one thing, her brilliance was in doing all of these things at once.

“There is a level of virtuosity in bringing everything together. She has a lot of agency in deciding who she wants to work with. She’s a corporate talent.”

Madonna took stereotypical images — Catholic schoolgirl, wanton woman, screen goddess — and gave them a twist. But her characters are always fluid. In the video for Open Your Heart, she appears as an exotic dancer being viewed through peepholes.

Then she destabilizes the scenario by showing that one set of watchers is a gay couple. Another is a young boy. At the end, Madonna puts on masculine clothes and skips away with the boy.

“You always question what you just saw,” says Burns. “She didn’t just set up these iconic types as absolutes. She always intervened.”

Adam Sexton was a music critic for the Village Voice in 1989 when he edited Desperately Seeking Madonna, an anthology of essays on Madonna, including the Paglia piece. He was inspired when he came across a newsstand in New York City and Madonna was on almost every cover.

Sexton is a bit of a begrudging admirer. “I was impressed. It was, and it remains, that she didn’t do any one thing extraordinarily well. But she has great taste and she’s obviously ambitious,” he says.

“Between these two things she managed to create multiple personae for herself. She wielded some sort of power in all of this. That was interesting to me.”

It’s old now, but back then there was something new about Madonna’s unapologetic attitude. She did what she wanted and declared that “the boy with the cold, hard cash is always Mr. Right.”

She appropriated anything she liked for her own purposes, from rosary beads to fetish gear.

“That her persona and presentation of herself would be spoken in the same breath as feminism was at first inconceivable,” says Sexton. “But she had an unapologetic attitude.”

Madonna burst onto the pop-culture scene when society was transitioning from Second Wave to Third Wave feminism and gender became a “fluid category,” says Janelle Wilson, a psychology professor who teaches collective memory and generations at the University of Minnesota Duluth.

“In many ways, American society wasn’t ready for multiple personae in the 1980s,” says Wilson.

“But fast forward to a time when individuals are creating and recreating their ‘images’ on their Facebook pages and you see a people embracing at least some of what Madonna may have been attempting to promote — that is, dissolving of binary categories, challenging conventional norms, creating spaces that are inclusive and accessible to people.”

In her social psychology class, Wilson presents the notion of “the self” — how we develop a sense of self, whether or not each of us has a core, stable self.

“I have seen in recent years how college students — members of the Millennial Generation — are not uncomfortable with the notion of having a mutable self, or even the possibility that we have multiple selves,” she says.

“None of us is ‘this’ or ‘that’ but rather, that we each are many things, including possibly contradictory things, but that this is not cause for alarm. Identities are complex and nuanced, not simple and fixed.”

Sexton is still not entirely convinced that what Madonna was preaching was feminism.

But it certainly seemed like something new at the time, even though it borrowed from already-existing esthetics and genres. Madonna helped define womanhood in small ways.

“Young women today accept that they can be contradictory things. You can be one person at work and one person at play,” he says. She also gave licence to the celebration of girlishness that was taboo for an adult female only a few decades ago.

“Like Sarah Jessica Parker as Carrie Bradshaw in Sex and the City,” says Sexton. “Carrie is ambitious and materialistic, but at the same time light, charming and girlish.”

Still, he doesn’t think young women are especially conscious of Madonna or the influence she may have had on their world.

There is the question of how to grow old gracefully as a pop star, whether it’s to rest on the laurels of your youthful productivity, like Paul McCartney, or to produce more obscure music for small pockets of people, like Prince.

“She’s not going away. She’s iconic for certain groups of people. But she’s not part of the conversation anymore,” says Sexton. “Her attempts to do that inevitably come off as desperate. No matter what she does, someone else has done something more tasteless or outrageous.”

Madonna’s halftime 2012 Super Bowl performance featured the Queen of Pop as a warrior, a cheerleader and a priestess. It was panned by some critics as shameless, but feminist writer Naomi Wolf opined that Madonna was getting slammed for sexist reasons, “because she is acting in the same way a serious, important male artist acts.”

In a riposte in Slate, J. Bryan Lowder conceded that Madonna hate “is a real and strange thing,” but he disagreed with Wolf’s argument.

“We don’t hate (or, for that matter, love) Madonna for her artistic genius. We’re just jealous of the fact she has been so successful without it.”

Earlier this year, Madonna flashed a 54-year-old nipple at a concert in Istanbul. This was no wardrobe malfunction. Despite the black bra and fishnets Madonna was wearing, the breast-baring was done in a deliberate and dispassionate way. Madonna obviously recognizes that this is still a radical act, says Burns.

In Russia, Madonna has protested the jailing of three members of Pussy Riot in a penal colony for the “punk prayer” they delivered in a Moscow cathedral in a protest against President Vladimir Putin.

During her European tour, she has used a video image of Marine Le Pen, the president of France’s far-right National Front, with a swastika on her face. After the threat of a lawsuit, the swastika was changed to a question mark.

When Burns introduces the video for Express Yourself and Like a Prayer to her undergraduates, there are sometimes groans in the lecture hall.

Still, she believes her students, who were born a decade after Madonna burst onto the pop-culture scene, appreciate it as a historical moment.

“The respect is still there,” she says. “I think she’s still considered to be very relevant.” But the real question is whether she’s relevant only in the eyes of an aging group of critics with a serious case of ’80s nostalgia.

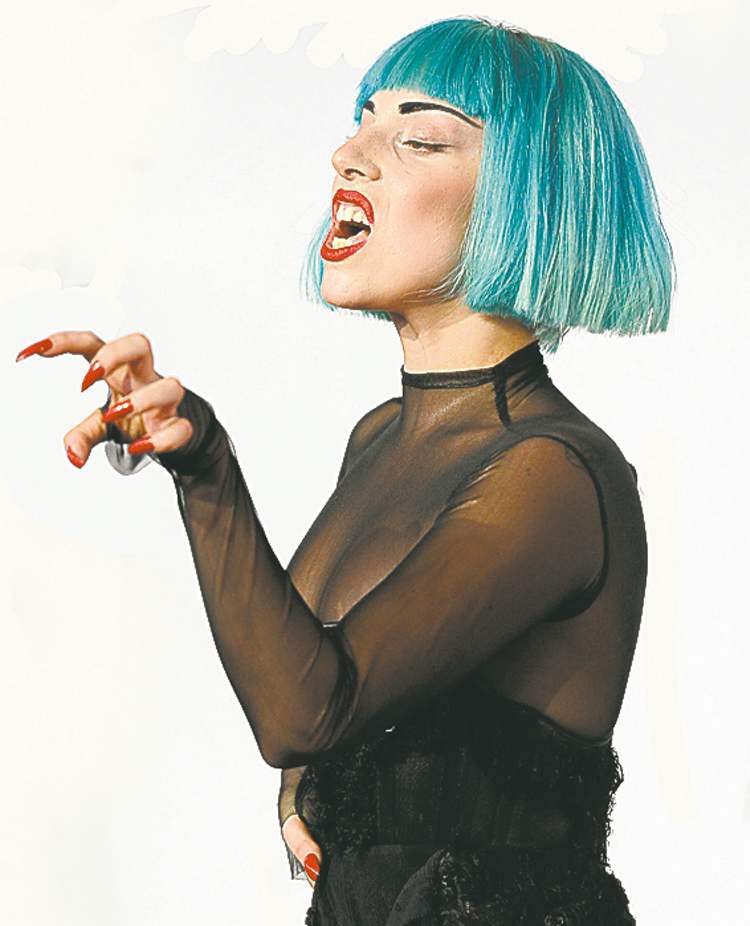

Two years ago, Paglia again reflected on Madonna in an essay about Lady Gaga, Madonna’s heiress-apparent. Gaga is another star with a theatrical, over-the-top style that underlines her message to “my little monsters”: be yourself.

Yet Paglia was unimpressed with Gaga, calling her a “manufactured personality” in contrast with the young Madonna’s “valiant life force.” Paglia wondered how a character so contrived and artificial could become the icon for a generation.

“Can it be that Gaga represents the end of the sexual revolution? In Gaga’s manic miming of persona after persona, over-conceptualized and claustrophobic, we may have reached the end of an era.”

For many critics, Paglia came across as no better than the aging punk rocker commenting that Green Day is nothing but a pale imitation of the Ramones. Two decades ago, Paglia declared Madonna the future of feminism. Like many of us, she seems distinctly uncomfortable with the present.

— Postmedia News

They’d be nothing without Madonna

Lady Gaga (right)

Ru Paul

Sarah Jessica Parker as Carrie Bradshaw

Paris Hilton (or any other celebrity who has ever appeared on a sex tape, but had the chutzpah to just keep on going)

Victoria’s Secret

LaSenza Girl

Material Girls

Pussy Riot