A dignified history

Manitoban gathers huge collection of archival photographs of early Icelandic immigrants

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 31/05/2011 (5338 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

HNAUSA — People didn’t smile in those old black-and-white studio photos a century ago because they had to sit still for so long due to slower camera exposures.

Or so people believe.

Or people will say, “My, those must have been hard times. Look… the people in those old photographs can’t even smile.”

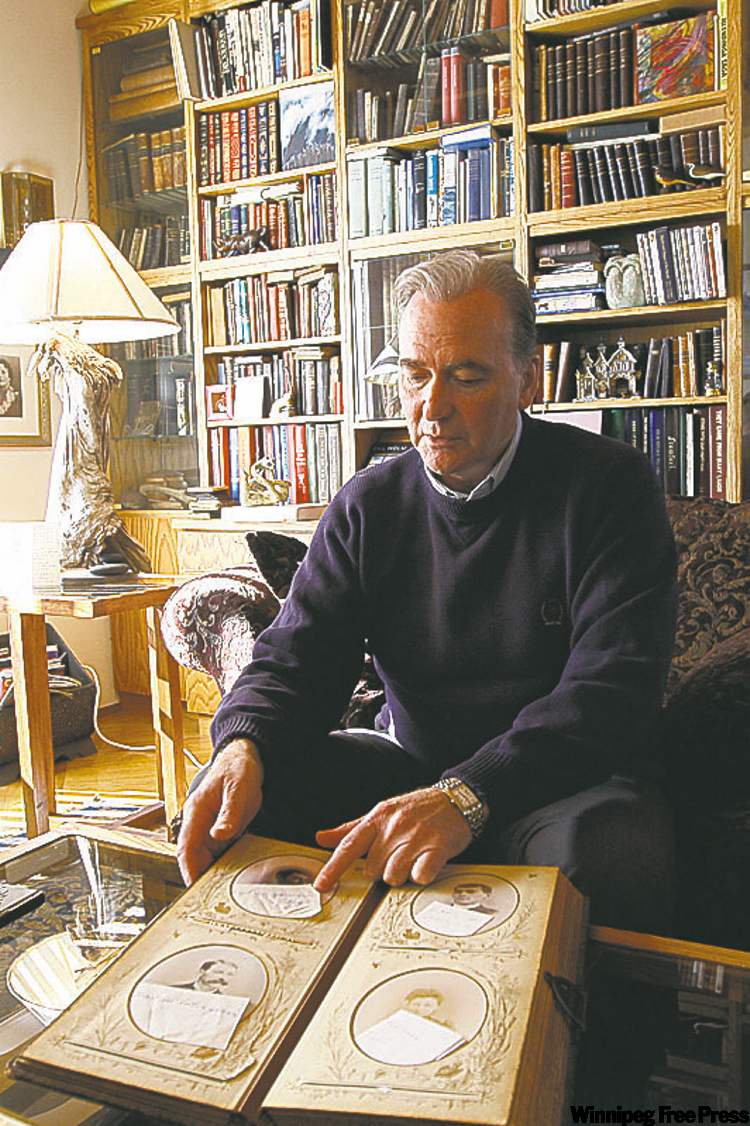

We’ve misunderstood the people in those photos for too long, said Nelson Gerrard, a collector of archival photographs of early Icelandic immigrants.

Those aren’t the reasons. The camera exposures were longer in the 1850s but not in the period 1880-1910 when waves of immigrants settled in Manitoba, said Gerrard.

What people fail to see is the importance our ancestors attached to the notion of dignity.

“In the Victorian era, the concept of a portrait was one of portraying dignity, a concept not easily understood today,” said Gerrard.

Smiling in photos wasn’t the fashion. The people in the photos tended to be the working poor and “wanted to appear like they had respect, self-respect, some kind of pride, self-worth, self-reliance,” Gerrard said. “It was a British Victorian kind of society where respectability looked a certain way.”

Gerrard has amassed the largest collection of early photographs of Icelandic immigrants to North America. (Icelanders didn’t just settle in Gimli but in places like Riverton, Lake Manitoba Narrows, Baldur-Glenboro, Swan River, Piney, Libau in Manitoba; in towns like Cavalier, Mountain, Edinburgh in North Dakota, and Roseau, Minnesota; and in larger cities like Winnipeg, Chicago, Seattle, Milwaukee, and Helena, Montana.)

“A lot of photos that would have ended up in burning barrels and landfill ended up on my doorstep,” said Gerrard.

In the process, he has turned into a kind of sleuth for identifying people in those images. He amazes others with his ability to track down the identities of subjects in old photos and put them into a historical context. “Nelson has helped many people find out about their families,” Almar Grimson, president of the Icelandic National League in Iceland, said during a visit to Manitoba.

Facebook is also coming in handy. Gerrard will post unidentified photos on Facebook hoping someone can provide a clue.

One thing he has discovered is that Icelandic immigrants had a penchant for being photographed. “I’ve never come across a body of work of one group that’s as extensive as that of Icelandic people,” he said.

Why did so many of those Icelandic families spend their meager savings on something so seemingly frivolous as studio portraits? Some families would pose for portraits every few years.

“The Icelandic people were really fashion-conscious. It was something in the blood,” said Gerrard, who lives in Hnausa, north of Gimli on Lake Winnipeg. “The photos show their interest in the arts and fashion. Also, the Icelanders were class-conscious. The photos demonstrate their ambitions to climb the social ladder.”

One has to cross the Atlantic Ocean to see Gerrard’s work on public display. His exhibit in Iceland has become a cornerstone for the increasing number of North Americans of Icelandic descent who make a pilgrimage back to the home country. Many will then travel to the sparsely-populated northeast coast where their ancestors mostly came from.

There, in the tiny village of Hofsos, is a modest visitor centre dedicated to those Icelanders who emigrated after the eruption of Askja, whose volcanic ash killed livestock and destroyed much of the land’s fertility.

The first surprise for visitors to the visitor centre is the brilliant exhibit inside comprised of archival photos of very high quality and sharpness, with wonderfully researched family stories with each photo.

The second is to learn that a former Arborg high school teacher is responsible for the exhibit. Gerrard, who grew up north of Brandon on a farm near Strathclair, put the exhibit together over a period of 10 years travelling to Iceland each summer.

“Some people stay there for hours going through the exhibit in detail,” said Grimson, of the Icelandic National League, which acts as a bridge between Iceland and people of Icelandic descent living abroad.

Seeing the exhibit (as I did last summer), one wishes every ethnic and religious group that ever arrived in Manitoba had such an exhibit in their native country that they or their children could visit.

The exhibit is called Silent Flashes, after a poem by Jon Runolfsson, an Icelandic immigrant to Manitoba during the first waves of immigration. In the poem, the flashes are lightning representing the souls of immigrated Icelanders returning to Iceland after many years of longing; in the exhibit, the flashes are the images of the Icelandic immigrants captured on camera.

Gerrard said people are always impressed not just by the sharpness but the artistry of the photos, including their composition: how people are posed, the backdrop, the whole presentation.

“These people are immaculately groomed, even though they didn’t have the gadgets we have today,” he said. “They had such beautiful clothing. A lot of it was handmade. A lot of these women were very skilled seamstresses. It showed what a priority it was to dress well.”

Gerrard, a fifth-generation Canadian of Icelandic descent, has had talks with the Winnipeg Art Gallery about opening a similar exhibit in Winnipeg. He is also writing a three-volume history on the pioneers of the Gimli area. In 1985, he published the book, Icelandic River Saga: A History of the Icelandic River and Ísafold Settlements.

Gerrard encourages all families to hang on to their family photographs. The biggest clue to the identities in any photograph is the family that owns it.

“It’s important that every family have a keeper of the family photographs, someone who listens to the old people talk, and records them and keeps records,” he said. “If you don’t have those people, the root is cut off, the continuity has been lost.”

bill.redekop@freepress.mb.ca

Nelson Gerrard collects archival studio photos of early Icelandic immigrants to Manitoba.