Manitoba’s winged women

In 1929, Eileen Magill and Dorothy Bell became pioneers in the Prairie skies

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/02/2022 (1424 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

By 1927, the demand for pilots was overwhelming and the government of Canada finally decided to promote pilot training.

To increase the number of qualified pilots and the construction of airfields, it encouraged the formation of “light airplane clubs” by providing funds to buy 10 light aircraft (such as the open cockpit 85-horsepower Cirrus Moth) as an initial issue to five clubs. In return the club had to build an airfield, hangar, hire an instructor and mechanic and assume responsibility for its own management. It also gave each club a grant of $100 for each private pilot it trained. A private pilots licence ran from $180-$240; a commercial licence from $500-$600 and just renting an aircraft to “build time” (no instructor) was $12/hour.

The response to the flying club plan was so great that by 1929 there were 23 flying clubs across the country. Women were not immune to what aviation could offer. Flying represented the ultimate escape from their everyday lives. It symbolized freedom and power and being in control of their destiny. They ignored the assumption that pilot candidates should be male and signed up for lessons.

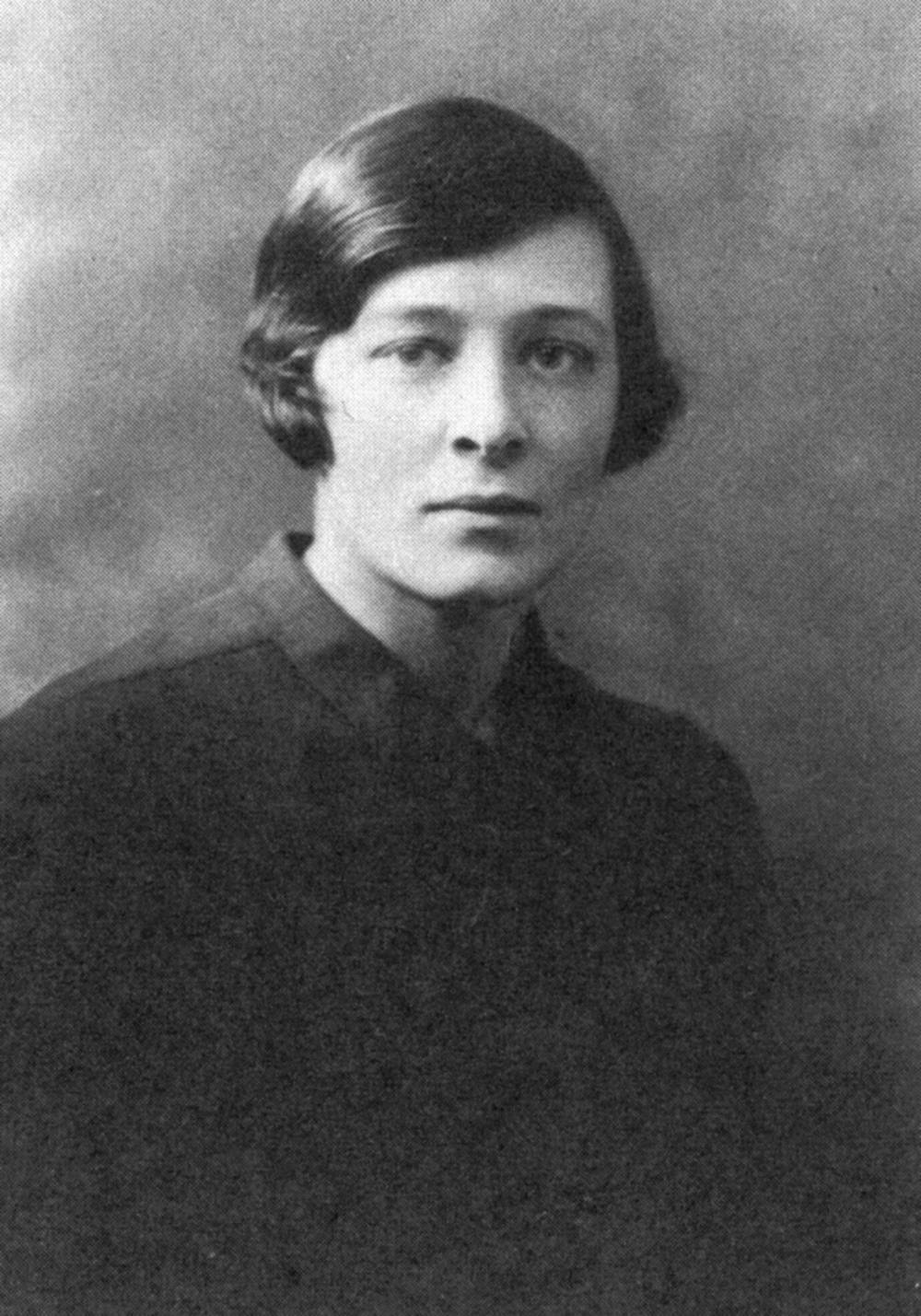

Eileen Magill (1906-1964) was Manitoba’s first licensed female pilot. Her family knew Jack McCurdy of Silver Dart fame. She was fascinated by the idea of flying. According to her brother, she was no meek, mild girl. Having already shocked her university classmates by smoking, wearing pants and driving fast cars, Magill joined the Winnipeg Flying Club at the west end of Sargent Avenue as soon as it opened its doors on May 29, 1928. She did not care that flying was considered unsuitable for young ladies.

The club’s first instructor was Michael DeBlicquy, who was described as “wonderfully unconventional and rumoured to be of Belgian royalty.” Magill and the rakish DeBlicquy were two of a kind.

Years later he said, “She was one of my first students. She did her first solo one summer evening and I guess she got carried away with being up by herself because all of a sudden it was dusk and she was at 5,000 feet. She put that damn Moth in a spin (to get down in a hurry) and recovered a bare 100 feet from the ground. I was really worried that she wouldn’t be able to pull out in time. When she climbed out I gave her hell for doing such a manoeuvre on her first solo.”

After 10 hours dual instruction and five hours solo, DeBlicquy told her she was ready for her flight exam.

Back in those days the flight examiner stayed on the ground while the student demonstrated his or her skill. According to DeBlicquy’s daughter-in-law Lorna DeBlicquy (a flight examiner in 1960s), the test in 1929 was designed to illustrate how the applicant would handle an engine failure, and if the pilot could recover quickly from an unexpected spin. The student had to fly several circuits during which he or she had to cut the throttle at a predetermined position and with no power, land at a predetermined spot. The final manoeuvre was to climb to 3,000 feet above the airfield and do a three-turn spin left and recover and then do a three-turn spin to the right and recover and land, with no throttle, to stop on a predetermined spot.

Magill had no problems with the spot landings, but she was a little concerned about remaining in a spin long enough to satisfy the examiner, RCAF Squadron Leader L. Stevenson. Her first spin was fine but she held her second spin for so long that both Michael DeBlicquy and the examiner did not think she could recover. She landed on the spot! The two men were amazed that she recovered from her long spin in the limited height remaining. Magill received Private Pilot Licence #142 Canada on Oct. 24, 1928.

Club members elected her to the board of directors. She was the first woman in the country to hold such a position. Outspoken and photogenic, with a gleam in her eye, she was a favourite of reporters who featured her whenever they could. A flight to St. Paul, Minn., warranted headlines in the Winnipeg Free Press, boasting that she was the first Canadian woman to fly across the border.

Magill flew for only a few years, since no one would give her a job in the aviation field even though the president of the Winnipeg Flying Club highly recommended her. Eventually she moved on to other challenges.

On Feb. 16, 1929 Dorothy Bell (1900-1987) became Manitoba’s second flying woman, and Canada’s fourth. A university graduate, Bell was the secretary to the president of the University of Manitoba. Her father was Dr. Gordon Bell and her brother was Dr. Lennox Bell. She fell under the spell of flying after a number of flights with the pilots of the RCAF and James A. Richardson’s Western Canada Airways, which was also based at what became Stevenson Airport. She was described as “an extremely vivacious girl with a total disregard for other peoples’ opinions.”

The flamboyant DeBlicquy was also her instructor. She described his instructions as unorthodox. “He just put me into the passenger seat (he was in the front seat) and told me to fly the damn thing. He told all of us that the club had only two aircraft and we would be murdered if we smashed either of the club’s aircraft. After 10 hours dual flying, Mike was all for pushing us into the air solo. A growl from the front seat — “You land it” — indicated you were ready to fly it alone,” she recalled.

However, being the centre of attention had its annoyances. “I was not just another pilot. Being one of only two girls had its drawbacks, because everything you did was noticed and remembered,” she said.

“One day I caught my ski in a snowbank while landing. The plane flipped over and I hung by my seat belt until was I rescued. Naturally, there was a crowd around to see my inglorious landing and of course someone wrote it up and sent it in to Canadian Aviation.

Bell and Magill often flew short trips together.

A quick learner, Bell qualified for her Private Pilot Licence #220 on Feb. 16, 1929. As it turned out, marriage and children ended her “pilot-in-command” days. However, because her husband was John Burdette Richardson, vice-president of James A. Richardson Ltd., she continued to fly into the North on Western Canada Airways/Canadian Airways Ltd. aircraft. She said that even though the flights sometimes had unscheduled night stops in the bush or travelled over uncharted territory, it did not bother her at all. She remained adventurous for the rest of her life.

Pilot Shirley Render, one of Canada’s foremost aviation historians, has been honoured with many awards and is the author of No Place for a Lady: the Story of Canada’s Women Pilots and Double Cross: the Story of James A. Richardson & Canadian Airways.