Hub of healing finds new life The lake — once a main draw for the sanatorium location committee — is still inarguably Ninette’s calling card

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/09/2023 (784 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

NINETTE — Mere months before the post office opened in Ninette, the German biologist Robert Koch peered into his microscope and spotted a deadly bacterium that would soon give the picturesque Manitoba town a life-saving purpose.

It was 1882. Koch turned his singular focus to pleural matters, studying a disease known colloquially as consumption, marked cinematically by a cherry-red cough splattered into a white-linen napkin.

Tuberculosis was a merciless killer, responsible for one-quarter of all deaths in Europe between the 17th and 19th centuries. But by the leading scientific minds of the era, the disease of the lungs was rom-comically misunderstood.

“Among the intervening causes of pulmonary consumption, I know of none more certain than sorrowful passions,” wrote René Laennec, the inventor of the stethoscope, in 1826.

That romantic pseudoscience was for generations “unquestioned dogma,” David S. Barnes writes in The Making of a Social Disease.

Until Koch looked down through his objective lens and saw a reddish rod that signalled the oncoming era of germ theory: rather than heartbreak, tubercle bacilli was the real killer.

Transferable through air by coughs and sneezes, the bacterium thrived in densely populated areas with poor sanitary conditions. While the disease’s cause was airborne, so too was one of its cures: clear air and isolation in an idyllic setting was often prescribed to help patients get back on their feet.

Manitoba wasn’t immune. In 1909, with both the population and the incidence of tuberculosis rising, the province searched for a location for a sanatorium — a haven of rest and relaxation for those suffering from the disease.

ARCHIVES OF MANITOBA The Ninette Sanatorium in 1910.

“The traditional sanatorium should be built in a quiet restful country,” wrote Dr. David B. Stewart, the son of the sanatorium’s first superintendent. Some municipalities weren’t keen on hosting a “pest house.”

“The thinking at the time was that in order to cure the disease, one needed to be in a bucolic environment, close to water and surrounded by fresh air,” says Neil Johnston, the CEO of the Manitoba Lung Association. It also needed to be along a rail line.

Ninette was exactly what the doctor ordered, and the sanatorium took in its first patient in May 1910.

“The San” became Ninette’s hub.

Dozens of residents worked there — in the kitchen, in the infirmary, maintaining the 103 acres of lush, green grounds, sequestered between the lake and an ever-rare Prairie valley — while medical professionals from across the country visited.

Hundreds of patients were treated at once, often for stretches of several years, bringing in a steady stream of visitors to the town’s train station.

“What really got this town on its feet was the sanatorium,” says Glen Johnston, the councillor of Ninette’s governing body, the local urban district. His mother received her nurse’s training there. Many in Ninette share a similar story.

In its original state, the sanatorium complex somewhat resembled an alpine retreat, the perimeter of its infirmary wrapped in airy verandas where patients would recline to respirate each day, not far from the lip of the lake.

Though it was a facility marked by illness, the patients who were well enough to do so kept life interesting. There was an Icelandic coffee club, there were Halloween parties, and there was an official sanatorium orchestra, with patients and staff playing together.

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS The old sanatorium in the town of Ninette

John K. Samson, a songwriter known primarily for his contributions to the renowned band, the Weakerthans, grew up hearing stories about the San from his mother, who grew up in nearby Killarney; a relative of hers had been a patient.

His mother would read passages from a book called A Hill for Looking, written by Martha Brooks, a Ninette author whose father, Dr. Paine, was one of the institute’s longest-serving superintendents.

“I can’t find my copy of it now, but it made a deep impression,” says Samson. “The close and isolated community of people from all over Manitoba, and the mysterious and frightening illness of tuberculosis, and the big, bustling complex of buildings.”

When Samson decided to focus on Manitoba roads for his 2011 album Provincial, he was drawn to Highway 23, giving him an excuse to explore the San in verse.

While doing research for his song, Letter in Icelandic from the Ninette San — “In another year, I’ll be buried or shivering here, coughing at the grey spittoon, painted orange by the harvest moon” — he made sure to explore the sanatorium, which was the province’s first public health facility. He calls it a “deeply haunted and beautiful place.”

As the sanatorium expanded, so did the town, located 200 kilometres southwest of Winnipeg, or about a 40-minute drive to Brandon. Along its main drag, grocery stores and hardware shops sprung up.

A curling rink was constructed, along with a hockey arena — nostalgic marks of a Prairie town’s true arrival. A constant flow of visitors arrived by train, where each locomotive was equipped with a separate sleep car for contagious patients being transferred to the San.

ARCHIVES OF MANITOBA Tuberculosis patients ‘taking the cure’ recline in the sanatorium’s sleeping pavilion in 1910.

Some patients, enamoured of Ninette, became permanent residents after they recovered. Of course, there were those who never saw their health take a turn for the better. While rest, nutrition and relaxation were helpful therapies, they were by no means a cure-all: death was a constant spectre in the town.

Indigenous people were not treated at the provincial facility until the 1960s, a government policy Johnston calls racist. In poorly ventilated, overcrowded residential schools, TB ran rampant: in the 1930s, the overall TB mortality rate in the residential school system was estimated to be 8,000 per 100,000, or eight per cent; in the general population, the mortality rate was somewhere between 50 and 79 per 100,000, or less than .1 per cent.

The arrival of anti-bacterial treatments in the mid-20th century revolutionized the battle against tuberculosis — which continues to affect over one million people worldwide — but in doing so, hastened the end of an era in Ninette history: the sanatorium closed its doors in 1973.

Fifty years have passed, and Ninette is as quiet and restful as ever, home to young families and retirees. And just as it did in 1910, a gentle breeze still crawls into town off the surface of Pelican Lake, where a group of young lakefarers prepares to set sail.

In 13-year-old Ben Schwartz’s humble opinion, Pelican Lake is the finest body of water in Manitoba. “It’s so peaceful,” says Schwartz, who’s been sailing Pelican for several years. “Personally, I like the calmness of the water.”

Schwartz, along with brothers Jace and Gavin Garabed, Aiden and Liam Sisson, and Alexander Grodek, was standing ankle-deep in the water, getting ready to launch from the nearby headquarters of the Pelican Yacht Club, founded in 1965 with Dr. Paine as its first commodore. The boys, all part of the club’s popular Learn to Sail program, were taking part in a generations-old summer tradition.

Pushing away from the shore, Capt. Schwartz climbed aboard, joined by Jace Garabed, 10, who quickly flopped into the water after splashing his superior. “That backfired,” he shouted, fluttering in the water.

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Ben Schwartz (left), 13, and Jace Garabed, 10, get ready to sail.

There was a time when falling into Pelican Lake was not so pleasant, says Brandon’s Trevor Maguire, a former Yacht Club member who moonlights as the chair of the Healthy Lake Committee.

The committee formed in 2012 in response to a stinky situation. Every five or seven years, the shallow body of water would experience a mass ichthyological die-off each spring, with expired walleye, jackfish and perch transforming Pelican Lake into a sulfuric seafood gumbo; the first one, the last one, and every one in between really did smell like a rotten egg.

“It stank to the high heavens,” Maguire says. However, the effect on the nostrils wasn’t as concerning as the effect on Ninette’s greatest natural resource and perhaps, its strongest asset.

Members of the committee knew the periodic fish deaths were suffocating the lake, flooding it with an abundance of nutrients like carbon and phosphorus and creating conditions ideal for cyanobacterial blooms, which coated the water with a thick scum of algae, depleting the water of oxygen. They realized quickly that the key to the lake’s overall well-being was year-round aeration.

“There’s not a lot of magic (being done) here,” says Maguire. “It’s aquarium science, expanded to the size of a lake.”

“There’s not a lot of magic (being done) here. It’s aquarium science, expanded to the size of a lake.”–Trevor Maguire

Maguire, an insurance agent and a one-time co-ordinator of Learn to Sail, is also the chair of the Western Manitoba Science Fair. “The Healthy Lakes Committee is my version of a science fair project,” he says, and it hasn’t been without its share of trial and error. Other aeration systems, Maguire says, weren’t designed with a cold climate in mind, so the committee leaned on the expertise of Gerry Paradis, a geothermal specialist.

The first system installed was an “unmitigated disaster,” says Maguire, who designed it. But as testing continued, subsequent systems showed immediate promise. Eight micro-bubblers were installed in the lake in the winter of 2012, and by the spring time. The next year, the volunteer committee installed 26 bubblers, leading to a 300 per cent increase in cubic feet of air per minute over the previous winter.

In 2015, the committee received $46,500 of funding from the Federal Recreational Fisheries Conservation Partnerships Program Grant and raised an additional $44,000 in local fundraising to establish its largest aeration field yet, a 98-bubbler system covering an area of 42 acres. At full capacity, the field can supply 350 cubic feet of air per minute.

Other communities have taken note, with similar technology being installed in Killarney Lake, Sandy Lake and Shoal Lake, north of Brandon.

The Healthy Lake Committee’s work has been a success from both an empirical and anecdotal standpoint. There have been no major die-offs since the systems were implemented, and in just over a decade, Pelican Lake has cleared up to a point Maguire expected to take 20 or 30 years. In 2016, Maguire could see the bottom of the lake for the first time in over 50 years of visiting.

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Bill Terry, 77, has been a member of the yacht club since the 1970s.

It’s a noticeable change, especially for yacht club members like Bill Terry, a shaggy-haired 77-year-old who has been a member since the 1970s. The lake is as clean as it’s been in his lifetime, he says.

Ninette’s thrived in large part due to volunteer effort, with community members rallying around common causes like the lake’s recovery or the refurbished Terry Fox Memorial Park, found in Ninette because Fox’s grandparents had lived in town. A young Fox would have spent his summers fluttering in Pelican Lake.

With cleaner, less nutrient-clogged water in the lake, fish also started biting the lure with greater zeal.

“Once the lake became more sustainable, there’s been much better fishing,” says Jaylene Evans, 32, who has lived in Ninette all her life. “A lot of people are now saying that Pelican Lake is a better spot for walleye than Lake Winnipeg, and that’s all because of the work the committee has done.”

The lake — once a main draw for the sanatorium location committee — is still inarguably Ninette’s calling card, its cleanliness creating a localized fishing and sailing boom.

Recognizing the shift, Evans and her husband Eric started E and J Live Bait out of their home in 2018, opening its first standalone store in January. Some locals refer to the shop as a small-town Cabela’s, referring to the outdoor recreation retail giant.

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Fishing on Pelican Lake is a major tourist attraction.

Pelican Lake is now enjoying a bit of a renaissance as outsiders learn of its charm, something insiders have known as long as they’ve called Ninette home.

“The town is excited, the campgrounds are full, and everyone seems very happy with the overall situation,” says Maguire. Now, the lake is staring down another potential problem as its popularity grows, posed by the potential arrival of invasive species.

“Zebra mussels are the main threat to this town,” Maguire says. The pesky invasive species hasn’t been spotted in the lake yet, so it’s imperative that boats from other lakes dealing with them don’t arrive and mess up that clean bill of health, he adds.

Carp, another invasive species, have already made their way into the water via the Pembina River, threatening to undermine the last decade of lake destratification.

Last spring, carp, which thrive in turbid water, were targeted and captured in known spawning areas using an electrofishing boat, stunning 1,186 of the fish before removing them from the lake.

Overall, the situation is still better than it has been in a long time, the next generation of Pelican Yacht Club members agree.

“Pelican Lake is the best,” says Jace Garabed, who quickly scampered back toward the sparkling water.

While established businesses like the Grocery Box and the Hot ’N’ Frosty restaurant endure, Ninette is attracting new investors on the strength of its lake’s notable improvement.

Among them is Ali Tarar, the owner of the grocery store for a decade. A former criminal lawyer in his native Pakistan, Tarar says that of all the places he’s lived in his life, Ninette is easily his favourite. “The people here are simply good people,” he says.

Also new in town is Corlee Pushka, a Brandon-raised real estate agent who moved to town in 2017. Pushka now owns the former post office on the town’s main street, converted into a 24-hour laundromat with an Airbnb rental suite on the second floor.

She also owns and manages a local gym, operates a few rental cabins, and operates the Pelican Campground and Lounge. She saw Ninette as a place “bursting with opportunity.”

The Hot ’N’ Frosty, the town’s classic drive-in restaurant, draws a daily crowd of day-trippers and motorcyclists, who’ve fallen for the newly paved sections of highways 18 and 23 near town, says Glen Johnston, wearing a Harley Davidson T-shirt. The restaurant is owned by Maguire’s daughter, Breanna Cullen.

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Ali Tarar, owner of the Grocery Box, is a former criminal lawyer who has lived in Ninette for 10 years after a previous career in Gujrat, Pakistan.

The town has changed significantly, says Johnston, especially considering the loss of the rail line and the closure of the local school in the 1990s. The curling and hockey rinks are gone too, with residents using facilities in nearby towns like Killarney. But as it nears 150 years old, Ninette persists.

Since it closed, the San has changed hands a few times, used for a stretch as a facility for adults with intellectual disabilities. Held in private ownership for nearly 20 years, the site, visible from the nearby Hill for Looking, named for Brooks’ book, fell into disarray.

“It has the perfect amount of disrepair,” says Alec Chambers, a Westman-based film producer who plans to shoot Homesick, an independent movie about a man driving his brother home from rehab, at the sanatorium in September. “Not quite destroyed, but not quite new.”

With the infirmary long ago demolished, an eerie quiet still permeates the verdant grounds. But the complex isn’t abandoned. In fact, someone just bought it, raising every set of eyebrows in and around Ninette.

“It has the perfect amount of disrepair. Not quite destroyed, but not quite new.”–Film producer Alec Chambers

“I took possession June 1,” says Geoff Gregoire, 42, who owns the Brandon-based company Contractors Corner and along with Pushka, his partner, owns and operates the lounge and campground.

His plans for the complex, whose doors are currently plastered with provincial health orders, are ambitious: he plans to convert the smaller buildings on the sanatorium grounds into condos and to renovate the large administrative building into a wedding and events venue.

There’s a lot of work to be done: mould and asbestos damage must be remediated, the leaky roof needs to be completely replaced and reshingled, and then come all the interior renovations and restorations.

“A complete cosmetic facelift is what it needs,” says Gregoire.

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

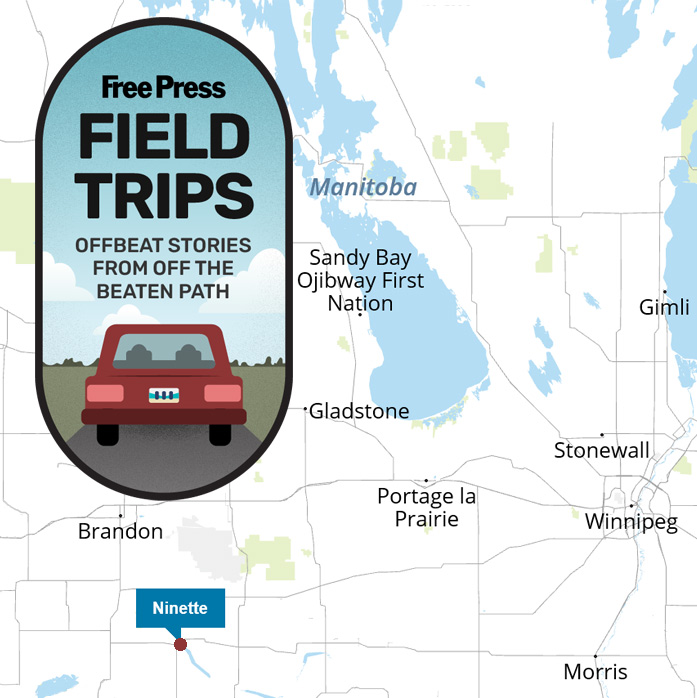

Previous Free Press Field Trips took us to Snowflake, Elma and New Iceland.

Ben Waldman is a National Newspaper Award-nominated reporter on the Arts & Life desk at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg, Ben completed three internships with the Free Press while earning his degree at Ryerson University’s (now Toronto Metropolitan University’s) School of Journalism before joining the newsroom full-time in 2019. Read more about Ben.

Every piece of reporting Ben produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, September 1, 2023 4:19 PM CDT: Changes to less than .1 per cent from .01