Keepsakes provide vital connection Tangible pieces of lives left behind help sustain Ukrainians making new homes in Manitoba

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/02/2025 (315 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Food, water, clothing and tangible reminders of home.

In the days and weeks following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022, the citizens under siege were forced to make an agonizing decision: stay in a dangerous but familiar world or run toward unknown safety.

Over the last three years, four million Ukrainians have been internally displaced by the war and 6.8 million more have fled the country. Each faced another impossible question: what to bring and what to leave behind?

Ahead of the third anniversary of the invasion — a milestone marked by revisionist lies and problematic talks of peace — three Ukrainian newcomers to Winnipeg share the stories behind the precious belongings they tossed into hastily packed bags alongside necessities for an uncertain evacuation.

These keepsakes, transported across war zones and between continents, are more than things. They are a connection to family, to faith, to prewar identity. A bridge between a new home on the Canadian Prairies and a homeland in turmoil.

All three have found work, housing and community in Manitoba. Still, Ukraine is never far from their minds.

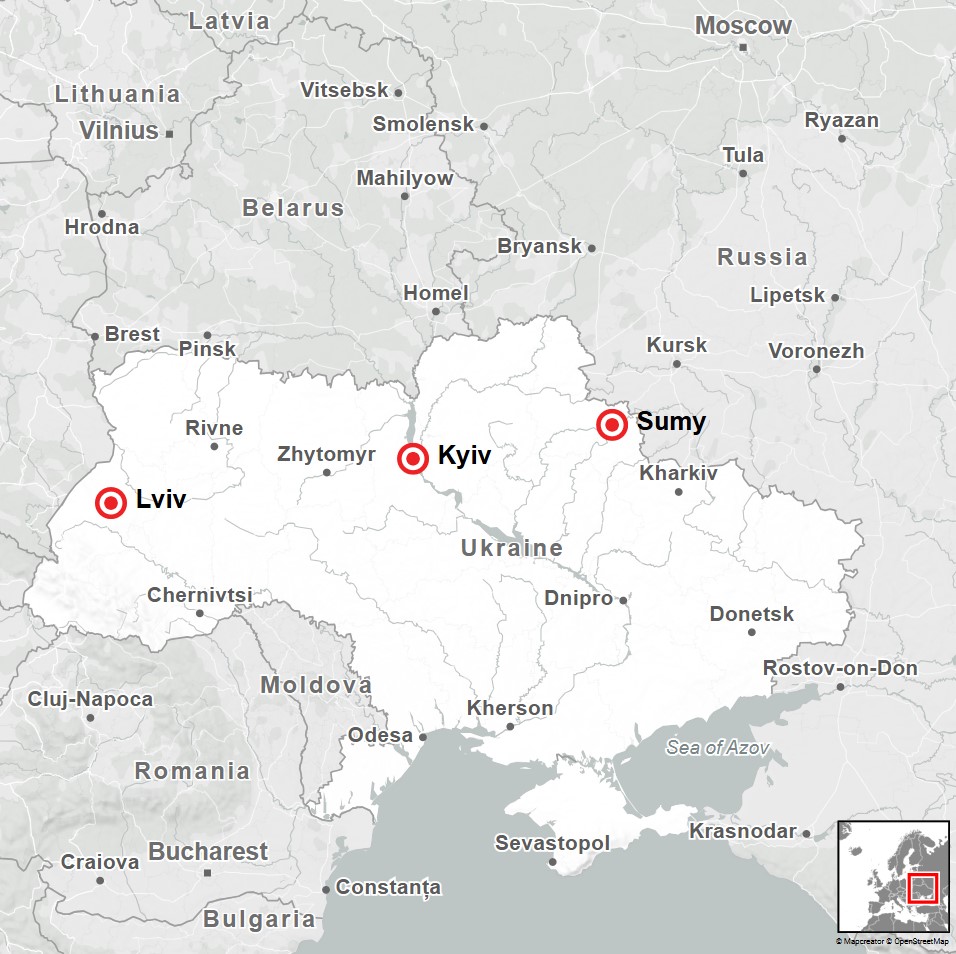

Sumy is an ancient city laced with rivers and situated about 40 kilometres from Ukraine’s northeastern border. Russian tanks rolled into town the first day of the invasion.

“It was like a nightmare,” Kristina Miroshnyk says.

She had missed her window. Amid rising concerns of a Russian attack in the region, Miroshnyk, 38, purchased train tickets and was set to depart for western Ukraine with her daughter on Feb. 23, 2022. Instead she stayed, hoping her instincts were an overreaction and that 21st-century diplomacy would prevail.

She woke up to a 5 a.m. phone call from a friend: the war had started. By noon, Russian troops were in Sumy.

Miroshnyk sewed up her emotions and tried to recall everything her grandmother had told her about surviving the Second World War.

As air raid sirens blared, she threw together a backpack with food, water, important documents, charging cables, a laptop and some family mementoes. She gathered her then six-year-old daughter, Kira, the family’s two cats and headed out to find shelter in the basement of a nearby home.

Sirens and shelters became a daily routine for two weeks straight, with Miroshnyk and the other parents trying to keep the kids calm and distracted as Russian military vehicles roved above ground.

Her husband Andrii, a carpenter, was abroad when the fighting started. Several friends were also away from the city at the time and Miroshnyk — who worked for an international education company — agreed to help escort their children and pets to safety.

After several failed attempts to evacuate residents from Sumy, she boarded a bus on March 8 with four kids and three cats. Two buses and one train later, she finally let herself cry at the Polish border.

The family reconnected in Greece, where Miroshnyk’s mother had lived for decades, before arriving in Manitoba with 350 other Ukrainian nationals on the first of three charter flights organized by the Canadian federal government in May 2022.

Keks and Kompot

“When we arrived here, we were joking that we came back to the ancestral lands of our cats,” Miroshnyk says of the family’s pair of Canadian sphinxes.

Keks and Kompot — names inspired by an animated Ukrainian cartoon and bestowed by Kira, which translate to Cupcake and Compôte, respectively — are hairless siblings with big, playful personalities.

Keks started out as Andrii’s pet, but Miroshnyk, a lifelong dog lover, was soon won over by the pink-and-black cat’s charm and intelligence. She offered to adopt his brother a few months later.

There was no question Keks and Kompot would be joining the evacuation.

“We still have family back in Ukraine, but no, I didn’t have any idea of leaving them there — it’s like two more kids,” Miroshnyk says.

“At first, they were pretty nervous and they were crying and they were shocked with the number of people, with the loud sounds. And they feel that I feel nervous with everything going on.”

Soon, however, the cats also fell into the difficult routine.

“There was a siren and we were grabbing backpacks, putting on our jackets and taking cats into the carrier. And I cannot find (the) cats,” she says. “I’m going around the whole apartment, trying to find them, and they were already inside the carrier. They didn’t like it, but they just went in.”

Miroshnyk packed food and water for the feline evacuees and swaddled them in baby diapers — a task neither party enjoyed. The cats travelled together in a small plastic crate or inside the jackets of their human companions.

Three years later, Keks and Kompot seem unscathed by their tumultuous journey. Today, they spend their days zooming around their Winnipeg apartment, performing for TikTok videos and getting into brotherly fights. And “because they have no fur, you can literally hear all those slaps,” Miroshnyk says with a laugh.

Religious icons

“These icons came from Athens, from Greece, where my parents were living, so they sent these,” she says.

The silver-plated images of Jesus, Mary and Saint Nicholas sit on a shelf in the family’s living room above a tribute to Miroshnyk’s mother, who died last year.

The icons were among the first things she packed when preparing to evacuate on International Women’s Day — a date seared in her memory because she had found some flowers for her daughter and mother-in-law and was about to dye her hair when the call came in.

“(The icons) kind of gave me more hope that everything will be better and maybe safe while travelling outside. The evacuation itself is very hard, emotionally and physically,” Miroshnyk says.

“You don’t really know that everyone will survive while evacuating, because (during) the previous evacuations (people) were shot and they were not successful. We were relying on everyone and everything in this world. And we were praying all the time. So having icons with me was a kind of feeling of safety. Or at least having hope that we were safe.”

Rushnyk

Miroshnyk and Andrii received this rushnyk — a ritual cloth embroidered with traditional Ukrainian patterns and blessings for happiness and good fate — on their wedding day.

“Normally, they’ve been sewn by a mother or a grandmother or a great-grandmother, and they’ve been given from one generation to another to another to another, and the older this rushnyk is, we believe the more power of the family,” Miroshnyk says, adding their rushnyk was ordered new for the occasion.

“When the Soviet Union formed, they were trying to destroy Ukrainian culture, Ukrainian language, Ukrainian traditions. Some people were digging our national clothes and rushnyks deep inside the soil for the next generation to find and have as a part of the culture.”

While Winnipeg is a safe, welcoming “second home,” the family’s heart remains in Ukraine. Every morning starts with coffee and reading news of the war. Andrii’s parents are still in Sumy and his older brother is an officer in the military.

“We are missing our people,” Miroshnyk says.

Daria Gorska had no intention of leaving Kyiv when the war broke out.

She and her husband were born in the Ukrainian capital, had raised their son there and had generational roots in the country’s most populous city. It was her mother, beleaguered from constant bombings and air-raid sirens, who convinced her to leave four days into the conflict.

Gorska, 39, along with her son, mother, aunt, father-in-law and two cats, loaded into a “very small, tiny car,” and spent five cramped days in heavy traffic with other evacuees heading for the Polish border.

They continued on to Germany and reunited with Gorska’s husband, Oleh, who had been working in Europe as a truck driver at the time — a blessing, since he would’ve been barred from leaving Ukraine under martial law, but one mixed with guilt for not having returned to join the fight.

Shortly after arriving in Winnipeg in April 2022, the couple found out they were expecting. Sixteen-year-old Gleb is now big brother to a smiley two-year-old sister named Leah, whom Gorska describes as the most precious package carried overseas.

Like everyone interviewed by the Free Press, Gorska had only minutes to pack up her life after the invasion began. The decisions were subconscious and the balance of practical to sentimental objects was determined by the size of her luggage.

There’s nothing she regrets leaving behind, but she does miss Ukraine’s food, coffee, architecture, medical system and her Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

She also pines for her cats, who’ve been taken in by friends and family, and her extensive violet collection — though she’s started cultivating a new crop of the flowering plants under grow lights in the living room of the family’s Winnipeg home.

Geiger counter

The yellow Geiger counter beeps to life at the press of a button. About the size of a smartphone, the device for detecting and measuring ionizing radiation was a key piece of workplace equipment during Gorska’s short but meaningful career as a tour guide in Chernobyl, the site of the worst nuclear disaster in human history.

“I have dreams about Chernobyl, not about Kyiv. I miss Chernobyl way more,” she says.

With a master’s degree in journalism and 17 years of experience in print, broadcast and radio reporting, she left the industry in 2020 after visiting Chernobyl. Despite lifelong skepticism of tourism in the exclusion zone, which is located about 100 kilometres north of Kyiv, Gorska felt renewed upon seeing it in person.

“It was big, fresh air for me to be in Chernobyl,” she says, adding years of crime reporting had left her burnt out. “I was expecting to see only debris, slums, overgrown buildings, nothing there. And I was like, wow, because it’s a place so different.

“First of all, it’s overtaken by nature. Trees grow through fences, through buildings, inside of the apartments. It’s so crazy. Plus there’s lots of wild animals, not frightened at all. You can see moose, bears and lynx, and even feed foxes from your hand — seriously, I don’t exaggerate; I can show you.”

Gorksa pulls up a video of her approaching an unfazed adult moose in a wooded grove.

Another video shows her using the Geiger counter to identify a radiation hot spot during a tour. The instrument clicks and then wails as the readings skyrocket around a manhole cover near the Pripyat mall — a comparatively luxurious shopping mecca in the model Soviet city — purpose-built to house Chernobyl’s employees and their families — prior to its evacuation in 1986.

“The Soviet Union collapsed when I was seven, so I had so-called ‘sweet memories’ of some things,” Gorska says, continuing to explain her complicated affinity for Chernobyl.

“Now I am aware of how bad it was for people, but this is something that you grew up with, and something that you lost forever. Nowhere else you can see monuments of Lenin, sickles and hammers, and these dolls that you remember when you were little.

“It’s like a frozen enchanted world, because people were evacuated quickly without a chance to take items with them. And it’s all still there. You come back to your childhood every time.

“And it’s silent. It’s a very special place.”

Winter boots

When Gorska and her husband learned their Canada-Ukraine Authorization for Emergency Travel application had been approved, she returned to Kyiv briefly to tie up loose ends and gather supplies for their future in the cold heart of Canada.

“That was a month after we left Ukraine, and I didn’t recognize my own city at all. The feeling was that somebody took the soul from the city,” she says.

“The thing I took from Kyiv the second time I left was only boots. Because I knew I was going to Canada, to Manitoba, and I was like, ‘OK, I have special boots for -40 C that I bought for Chernobyl.’ So, I had a suitcase with only boots inside.”

Religious icon

“Being a journalist, I had lots of work trips,” Gorska says.

“This icon was always with me, wherever I went.”

The small worn copy of the religious icon, entitled Support of the Humble, depicts the Virgin Mary and infant Jesus shrouded in gold haloes.

When a print of the icon was placed in Kyiv’s Vvedensky Monastery, the image was mysteriously transferred to the glass covering the artwork.

“Lots of miracles happened after that,” she says.

“I got this icon because I was singing in that monastery when I was a child.”

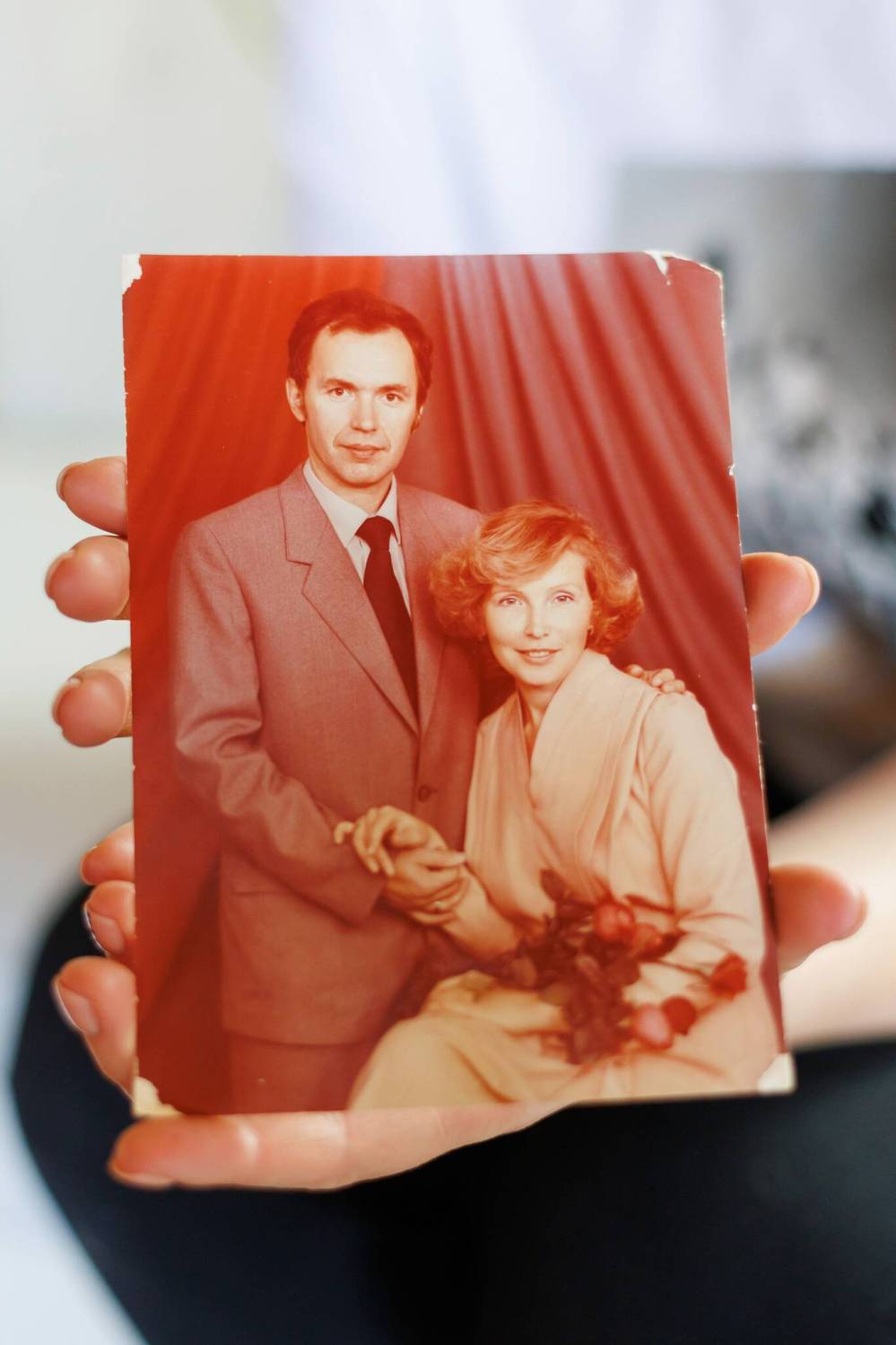

Wedding photo

“My father passed away in 2004 and I didn’t know if I would see my mom again, that’s why, for me, this photo was something important,” Gorska says of the photograph of her parents, Oleh Gorsky and Natalia Lohinova, on their wedding day.

She hopes to one day be able to return to the cemetery where her father is buried.

“I want to visit Ukraine,” she says. “I’m not sure that I want to live there, because it’s not the Ukraine that I left. It’s a different country. It’s a different city now. If I had stayed there, I probably would not feel the same way.

“People there are changing together with the circumstances. But if you left it behind and then came back, the difference is so big, you know? I’m afraid I will not fit in.”

A self-professed romantic, Olesia Chychkevych swoons when she talks about Lviv.

“It’s like a fairy tale,” she says, describing a lively urban centre filled with historic architecture and an aroma of chocolate and coffee.

Chychkevych, 48, moved to the western Ukrainian city for university and stayed when she found a teaching job. She worked at the same school for 18 years and, with her husband, raised three boys there: Nazariy, 24; Bohdan, 17; and Danylo, 6.

“Here, I try to teach my kids to value each second of our life because in Ukraine I had a lot of plans,” she says. “And those plans, in one day, popped like a bubble.”

The first night of the Russian invasion, Chychkevych awoke to a cacophony of sirens. She and her sons descended from their 17th-floor apartment to shelter in an underground parking lot packed with other residents.

Danylo, who was four years old at the time, spent the day with his arms wrapped tightly around his mother’s neck. He was crying and shaking, unable to sleep.

Chychkevych knew, for her son’s sake, she had to leave. They packed quickly and boarded a train crowded with other mothers and children bound for Poland, where her eldest son was attending university. The trip, which would normally have taken four hours, lasted nearly a day.

They stayed with a friend’s relatives and waited for Nazariy to finish his semester before coming to Canada, landing first in Toronto and then Winnipeg in July 2022. Her husband is still in Ukraine.

The boys are working or attending school and Chychkevych has been able to continue with her “favourite job.” She’s currently employed as an educational assistant in a local elementary school and is in the process of getting her Manitoba teacher’s certificate.

Sourdough starter

When it was time to evacuate, Chychkevych packed up a small portion of her sourdough starter at the request of her sons.

“They asked me, ‘Mom, are you going to make bread for us like you do at home?’” she recalls.

A university friend taught her how to make the involved homemade bread and she’s been tending the same starter — a living culture of yeast made from fermented flour and water — for the past seven years.

“It is like special therapy for me,” she says of breadmaking. “Because always when I’m making it, I’m using no machines; I always make it with my hands and I’m thinking only about positive things.

“I try to pray at this time and it seems like this bread heals … it has to help us be healthy because all my positive energy, I put there.

“And you can’t imagine how beautiful the smell of the house is when I’m baking.”

Chychkevych bakes a loaf every week. Even though the recipe and taste have been altered slightly by a new climate and new ingredients, the impact is the same.

“My kids, they respect (the bread) and sometimes my youngest will hold a piece and kiss it because it reminds him of home,” she says with a lump in her throat.

Handmade dress

Chychkevych’s babcia Yevhenia made every piece of this cherished item by hand, from the fabric to the colourful floral embroidery to the lace detailing on the sleeves and hem.

“She was working on the farm and at night when she came home and kids were sleeping, by candle she was making this,” she says.

“When I feel so upset, because I spent a lot of time with my grandma, I put this dress on and it has a special power — it gives me wings.

“Because our family always takes care of us. For me, it’s like a piece of happiness.”

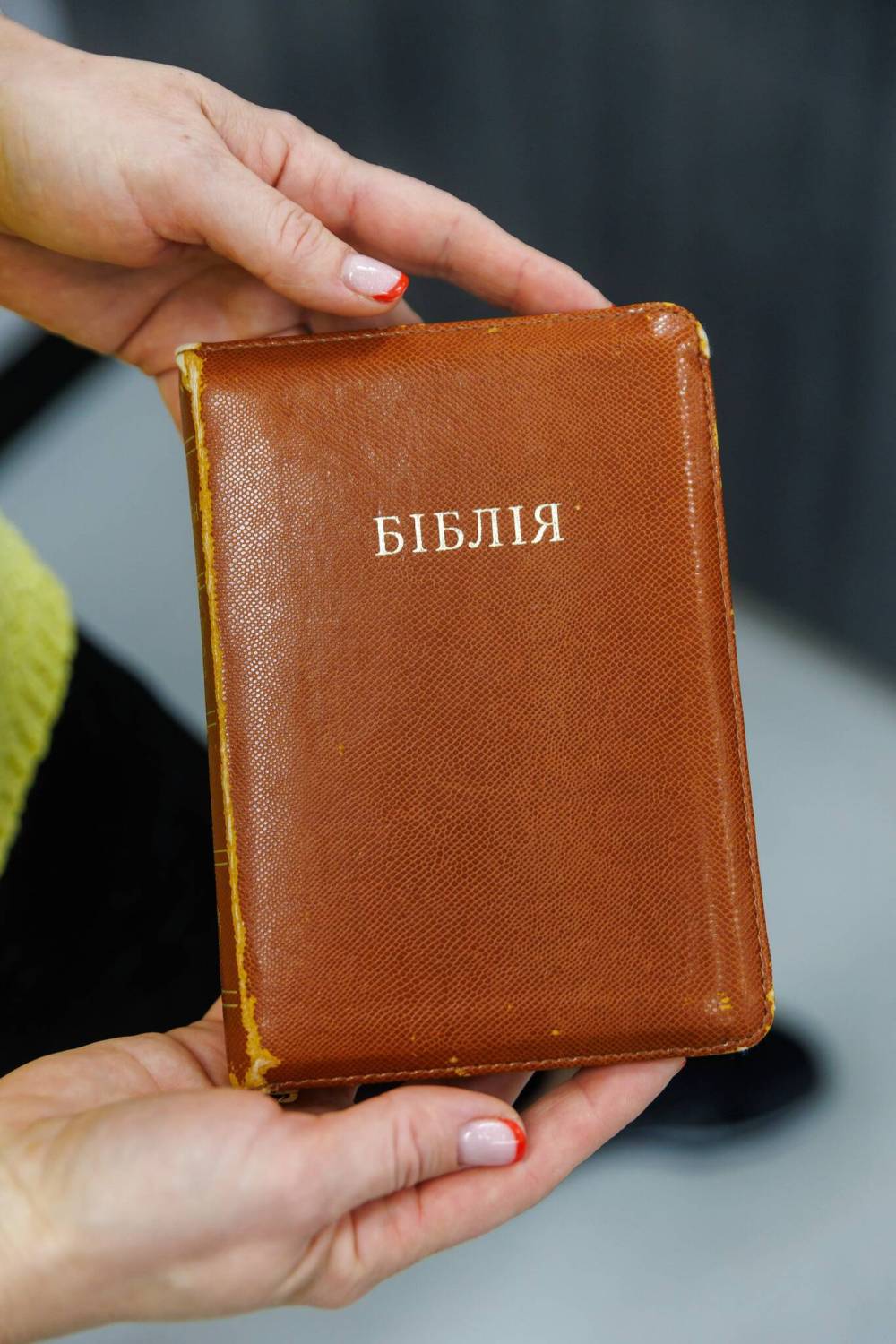

Bible

“This is maybe the thing that helped me to feel more protected,” Chychkevych says of the leather-bound Bible gifted by a friend.

“Really, God helped us because we came here. We had no friends, no relatives, no one.

“And I’m so happy because here the community was great.”

She considers the family’s arrival in Winnipeg a form of divine intervention.

During a sleepless night in Toronto, wondering how she was going to survive in such an expensive city, Chychkevych started praying for an answer.

“I had no time to go to church, but my grandma told me, ‘God is like your dad, just talk like with your dad.’ So I started talking: help me, show me the way, Canada is so huge. And just randomly I thought ‘Manitoba,’” she says.

“In the morning I told my kids we are going to Manitoba.”

Winnie-the-Pooh

Before heading to the train station, middle child Bohdan packed a bag with a laptop, some books and clothes. Tasked with choosing only a few toys to bring, the youngest, Danylo, picked out a single Hot Wheels car and his Winnie-the-Pooh stuffie.

“When my friends came to visit my newborn son, they brought this toy as a present. And still everyday he’s talking with him like it’s his best friend. Winnie knows everything, all his secrets,” says Chychkevych, who was unaware of the honey-loving character’s connection to Winnipeg.

Chychkevych sought assistance from the Manitoba branch of the Ukrainian Canadian Congress upon her arrival to the city. Among other things, the organization helped her outfit the family’s first apartment with donated furniture and arranged a special surprise for Danylo.

“He was missing his toys a lot,” she says. “At the end of the week, they brought him two huge boxes of different cars, Paw Patrol stuff, everything. You can’t imagine his face when they entered the room … people here are so helpful.”

As a member of the modern Ukrainian diaspora, Chychkevych has been intentional about building community in Winnipeg, while continuing to celebrate her cultural identity. For her, setting down roots is an act of resistance.

“The main reason I’m doing this is to save my kids, because it’s our future. We have to save our generation because this war is not between countries. It seems to me that Russia just wants to destroy our people, destroy our traditions.

“Now (Ukrainians) are all around the world, but in each country everyone tries to keep our language, keep our songs, keep our national embroidered clothing,” she says.

“We have to make everywhere feel like home.”

eva.wasney@winnipegfreepress.com

Eva Wasney has been a reporter with the Free Press Arts & Life department since 2019. Read more about Eva.

Every piece of reporting Eva produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.