How Canada can regain its measles elimination status

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

TORONTO – Infectious disease experts say Canada’s loss of measles elimination status shows how badly investment is needed in public health, rebuilding vaccine confidence and solving the primary care crisis.

On Monday, the Pan American Health Organization revoked the measles-free status Canada has had since 1998 because an outbreak of the virus across several provinces has lasted for more than a year.

McMaster University immunologist Dawn Bowdish says cuts to public health funding, the lack of a national vaccine registry and a shortage of family doctors — all while misinformation about vaccines is circulating widely — have contributed to the rise of measles.

She says public health workers don’t have the resources they need to do enough vaccination outreach to communities and bump up surveillance to quickly identify cases and stop transmission.

Bowdish says not having a national vaccine registry means many people can’t easily find out if they’re up-to-date on their immunizations if they were vaccinated in another province or country.

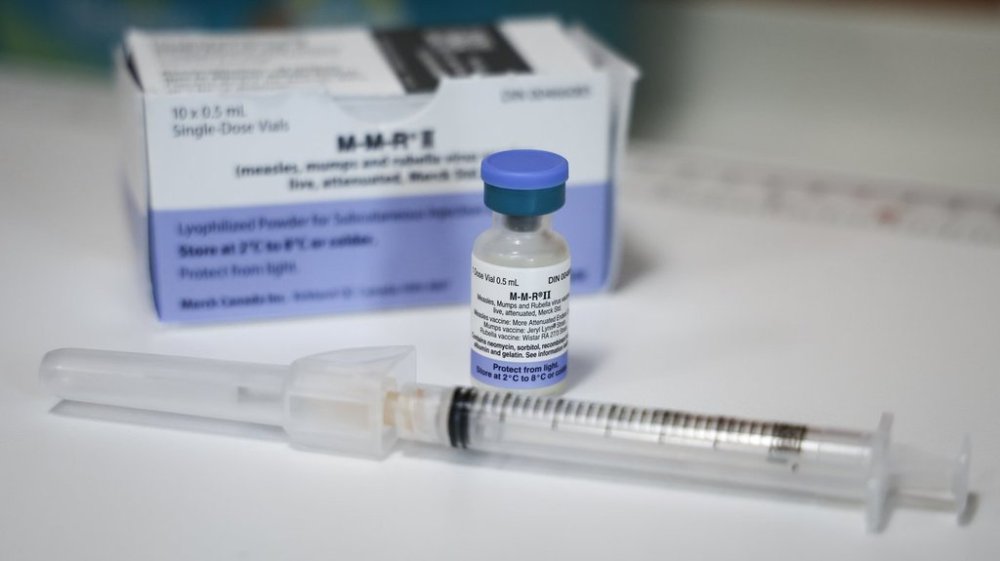

She says if families don’t have a primary care doctor or nurse practitioner, their kids are at risk of missing vaccinations since pharmacies don’t do measles, mumps and rubella immunizations for very young children.

“Inevitably, if you don’t have good consistent care, these are the kind of things that get dropped,” Bowdish said.

Measles, one of the most contagious diseases in the world, requires 95 per cent vaccination coverage to obtain herd immunity.

Bowdish said tougher enforcement of school vaccination policies, essentially restricting exemptions to valid medical reasons, is critical to stopping the spread.

“One of the things that my colleagues and I have been saying for a long time is many of the provinces, including Alberta and Ontario — the epicentre of these outbreaks — we’re way too liberal with our exemption rules. And that has contributed to falling vaccine rates.”

To get its elimination status back, Canada will not only need to stamp out the transmission of the current strain for at least 12 months — it will also need to show that it has beefed up its surveillance systems and ability to quickly stop outbreaks if measles cases arise, the Pan American Health Organization said on Monday.

Bowdish said the return of measles in Canada “shows how many systems will have to be fixed for us to get this under control.”

“We’ve been trying really, really hard for over a year and I don’t disparage any of my colleagues in public health because I know they’ve been losing sleep trying to do the best they can with the resources they have,” she said.

“There’s no two ways about this. This will take money — a lot of money — and a lot of investment. And it will take a lot of political will.”

Dr. Daniel Salas, executive manager of PAHO’s Special Program for Comprehensive Immunization, said Canada will need to finish implementing its national electronic vaccine record system, which at the moment only accounts for five provinces and one territory.

Dr. Monika Naus, a professor in the School of Population and Public Health at the University of British Columbia, said it’s critical to sort out what’s happening in communities with low vaccination rates, including determining whether children were immunized but their records are missing or if they are actually unvaccinated.

“That really is something that the public health community should be able to get a handle on,” she said.

PAHO also recommended presenting a corrective plan to continue breaking down barriers to understand the perspectives of the close-knit unvaccinated communities where measles has spread.

Naus, who has previously served as chair of the National Advisory Committee on Immunization and as medical director of vaccine preventable diseases at the BC Centre for Disease Control, said those targeted efforts are critical and make a difference.

“It’s probably false to consider that people who are resistant to vaccination will never be vaccinated under any circumstances,” she said.

“Even in communities with low uptake rates, there are probably (public health) improvements that can be made.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Nov. 11, 2025.

Canadian Press health coverage receives support through a partnership with the Canadian Medical Association. CP is solely responsible for this content.