Turbo4 versus V6

Do smaller turbo engines really offer better real-world fuel economy?

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/07/2013 (4497 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

A few months ago, Consumer Reports magazine decried the supposed fuel-economy advantage of small turbochargers over the larger (typically V6) engines that they are supposed to supplant.

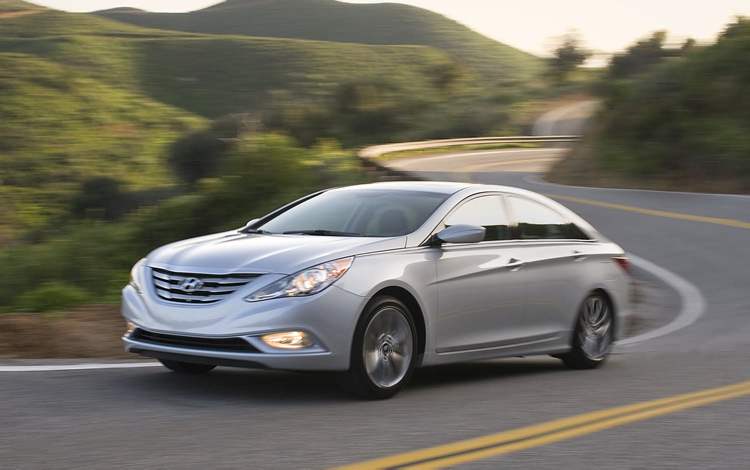

So it was that a Ford Fusion 2.0L EcoBoost, a Hyundai Sonata Turbo and a Honda Accord V6 (not to mention the base Hyundai 2.4L Sonata and Sonata Hybrid brought along as baselines) appeared for some real-world fuel-consumption testing.

Why does turbocharging save fuel? The lure of turbocharging as a fuel-saving measure is easily understood. It allows a small-displacement four-cylinder to replace the more thirsty V6, thanks to the availability of turbo boost. This allows a smallish 2.0-litre four-cylinder to produce power equal to that of, say, a 3.5L V6.

It’s not quite the promise of the perpetual-motion machine, but turbocharged engines nonetheless seem to offer something of a free lunch.

It’s a theory that bears fruit, at least theoretically, in Natural Resources Canada’s official fuel-economy ratings. Both of our turbocharged models, the Sonata and Ford Fusion, are officially rated for 0.5 L/100 km better city mileage than the naturally aspirated 3.5L Accord. Both consume marginally more than the Accord on the highway — 5.8 L/100 km for the Sonata Turbo and 5.9 for the EcoBoost Ford versus 5.7 L/100 for the surprisingly parsimonious Honda — but both still rate a superior overall fuel economy.

However, our first conclusion of the day was that replicating NRCan’s rated city fuel economy, in any of the cars, would require the patience of Job and the sensitivity (in the right foot, at least) of Mother Teresa. The trio consumed, on average, three per cent more fuel driving around the city than the government agency estimated.

Judging from past testing, this was hardly surprising. But what was very surprising is that the big-engined V6 Honda was the most frugal in the city — its 11.8 L/100 km (against a rated 9.7) was vastly superior to both the Sonata Turbo (12.6L/100 km real-world versus a rating of 9.2) and the Ford Fusion EcoBoost (13.6 L/100 km versus a rating of 9.5 for our AWD version).

Not only did the Accord consume less fuel than the two turbos, it did so despite the worst NRCan rating of the trio. The answer to that seeming conundrum — and, indeed, perhaps the reason why the Ford sucks back more gas than the similarly engined Sonata — lies in the very nature of turbochargers.

Essentially, a turbocharger is a small fan in the exhaust pipe that uses the hot, fast-moving gases expelled from the engine to drive another fan to force-feed the intake side. That’s the part of the equation that lets a small four produce the git-up-and-go of a big six.

The trick, however, when you’re looking for better fuel economy from a turbocharged engine, is to baby the throttle so as not to awaken that fan. Keeping the turbocharger dormant is key to keeping the engine sip-sip-sipping along like the little four-cylinder all those fuel economy-oriented ads promise. If you can manage to feather the throttle right up to the point that the turbocharger kicks in, you should, again theoretically, garner some fuel-economy savings.

Unfortunately, as our tests (and those of Consumer Reports) show that maintaining that delicate balance is a little like trying to tiptoe out of your bedroom for that illicit 18 holes while carrying a big Arnold Palmer golf bag on your shoulders. It’s theoretically possible, but the klink-klink of the putter against sand wedge almost always results in more mowing of lawns.

In fact, the more interesting aspect of the comparison is that the Sonata Turbo seemed more frugal than the EcoBoost Fusion despite sporting 34 more horsepower (274 hp versus 240). Part of Ford’s disadvantage can be traced to it being the only all-wheel-drive sedan in the segment. But, by Ford’s own reckoning, that only accounts for 0.3 L/100 km of the 1.0 L/100 km disadvantage we noted.

Further explanation may be gleaned by how Ford tunes its EcoBoost four. Although the Sonata has a full-throttle acceleration advantage thanks to its horsepower superiority, it’s the Ford that feels more responsive upon initial throttle tip-in.

Our conclusion is that Ford has configured its turbocharger to “spool up” more quickly than the Hyundai’s, a boon for performance feel, less so for fuel economy, as it’s more difficult to feather the throttle for those promised fuel-economy gains.

The same conclusion may well be ascertained from our observed highway fuel-consumption findings. Here again, the numbers were surprising: The Accord V6 and Sonata Turbo posted largely identical numbers (4.9 L/100 km at 80 kilometres an hour), while the Accord squeezed out a 0.1 L/100 km advantage at 100 km /h (5.3 versus 5.4). The Sonata Turbo returned the favour at 120 km/h (7.2 L/100 km versus the Accord’s 7.3).

And the Ford Fusion? Well, unfortunately, the Fusion sucked back 6.1 L/100 km at 80 km/h, 6.9 at 100 and a whopping 9.4 L/100 km at 120 klicks.

Why the big difference? To be truthful, without a laboratory and direct access to Ford’s fuel-injection software, it’s impossible to posit a definitive answer to this question. A good guess might again be that Ford tunes its EcoBoost engines for the throttle response that consumers want (the Fusion’s 270 pound-feet of torque was the highest in this test, and the 2.0L EcoBoost is very responsive) as well as the fuel economy that will pass government tests.

That combination makes it difficult to replicate NRCan’s claimed fuel economy, as it’s very easy to slip from off-boost fuel-sipping mode to pump-up-the-volume turbo engagement.

Whatever the reason, the case for turbocharger engines saving fuel compared with their larger naturally aspirated competitors is inconclusive at best. The better of our two samples, the Sonata Turbo, equalled the Accord. The Fusion 2.0 was, by some margin, more profligate.

In the final analysis, our real-world numbers turned out not to be so different from Consumers Report’s findings. Its test showed the EcoBoost Fusion consuming four miles per gallon more overall (22 US mpg versus 26) than the Accord V6; that equates to an advantage of about 1.6 L/100 km for the naturally aspirated Honda.

Our tests, though almost assuredly less scientific, revealed a strikingly similar 1.9 L/100 km advantage for the Accord over the Fusion. And, indeed, the comparatively minuscule 0.4 L/100 km advantage (26 US mpg versus 25) that Consumer Reports found for the Accord over the Sonata Turbo matched our margin exactly.

In future tests, we may evaluate even more similarly motored cars — Kia’s turbocharged Optima, the BMW 328 and Audi’s A4 2.0T representing turbocharged engines and the Nissan Altima and Toyota Camry boosting the V6 side. But our initial investigation would seem to indicate that turbocharged engines are a bigger boon to the government’s regulatory mandarins than real-world drivers.

— Postmedia News