Social justice minister

Cleric's stance on labour, war ruffled feathers

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/05/2019 (2392 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In 1916, William Ivens walked through the doors of the McDougall Methodist Church in Winnipeg’s North End to begin his career there as its minister.

Trouble followed him a short time later.

Ivens’ message of better wages, safer working conditions and the right to unionize attracted many new members from the church’s working-class neighbourhood. However, his pro-labour stance and objection to the Great War upset some leaders of the congregation.

In the spring of 1918, he was expelled from his church by a board dominated by people from the wealthier south end of the city. They couldn’t live with his increasingly vocal support of the labour movement.

In his last sermon at the church, Ivens stood his ground.

“If Jesus were here at this hour, he would be swallowed up in an impassioned denunciation of the system of capitalism of today,” he railed from the pulpit.

“(It was) a crime against heaven that children should starve amid plenty,” he continued, adding there “was but one solution to this monstrosity: the workers must own the tools of production.”

The church board’s decision set the stage for Ivens to take on one of the key roles in leading the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike.

“You can’t tell the story of the Winnipeg General Strike without telling the story of William Ivens,” says Nolan Reilly, a retired history professor at the University of Winnipeg and author, along with his wife Sharon, of a walking and driving tour of the general strike.

Ivens, Reilly says, believed Christianity shouldn’t just be about the sweet hereafter, but about what is happening today.

“He believed you couldn’t be a Christian if you weren’t outraged by the plight of working people and not actively engaged in bettering their lives. For him, that was the message of Christianity.”

Ivens was born in England in 1878 and emigrated to Canada in 1896. He worked first as a farm labourer in rural Manitoba before beginning studies at Wesley College — today the University of Winnipeg — in 1902.

While there, he was influenced by faculty who were prominent social gospellers, a movement that called on Christians to address the needs and injustices of the world around them.

He graduated in 1906 with a BA and a bachelor of divinity in 1907. Ivens married a year later and began his ministry as a rural Manitoba pastor. In 1909, he earned an MA in political economy from the University of Manitoba.

In need of a job after his firing from the Methodist church, Ivens soon became editor of the Western Labor News, a pro-labour newspaper. Then in July 1918, he started the Winnipeg Labour Church, a new kind of place of worship aimed at applying the principles of Jesus to the lives of the working class.

“(The church clearly identified) with workers who fared poorly in the existing capitalist system and in direct opposition to the status quo in politics, business and religion of the time,” Michael William Butt wrote in his 1993 master’s thesis.

Winnipeggers responded. The church had more than 4,000 members after six months. They were attracted to its message that capitalism had failed and they were going to build a better world, Reilly says.

Along with providing information and inspiration, the church also gave workers spiritual justification for striking, he adds, telling them “striking is a legitimate tactic for a Christian, even if the established church said no.”

Just like other churches, the Labour Church opened and closed with prayer, had sermons and took collections. It even had its own hymns — familiar tunes with new pro-labour lyrics written by Ivens.

It was different in other ways. It was non-denominational, non-hierarchical, owned no buildings and allowed non-ordained people to speak — including women.

Services were held in various parks, schools and other locations around Winnipeg; at one point, there were at least nine congregations meeting in the city.

The biggest gatherings were in Victoria Park in the East Exchange. As many as 7,000 people came to services there.

After one service, Ivens wrote: “Victoria Park is fringed with trees which constitute the walls of the Labour Church; the greensward is the floor and there are no rented pews; the pulpit is a rough platform in the centre of the park; and the sky, illuminated by the stars, constitutes the roof and dome. Never has a church service in Winnipeg had such a gathering. It will never be forgotten while this generation lives.”

In his sermons, Ivens preached that “Christ was not just a saviour, Christ himself was the ultimate social reformer,” writes Vera Fast in Prairie Spirit: Perspectives on the Heritage of the United Church in the West.

Ivens proclaimed the existing capitalist system was vicious, and had to be challenged and replaced with a system that offered a new world order built on an understanding of production for use, not profit, Butt wrote.

While working people flocked to hear him, Ivens and his church were condemned by preachers in other pulpits.

In his book about the Labour Church, J.S. Woodsworth wrote it was made stronger “by the opposition of the ministers and the churches to the strikes … class lines became clearly drawn and the ‘regular’ churches stood out as middle-class institutions.”

Ivens was unfazed by the criticism. Other preachers had lost their way by siding with the rich and the ruling class and by supporting a capitalist system that legitimized the exploitation of those in greatest need, he said.

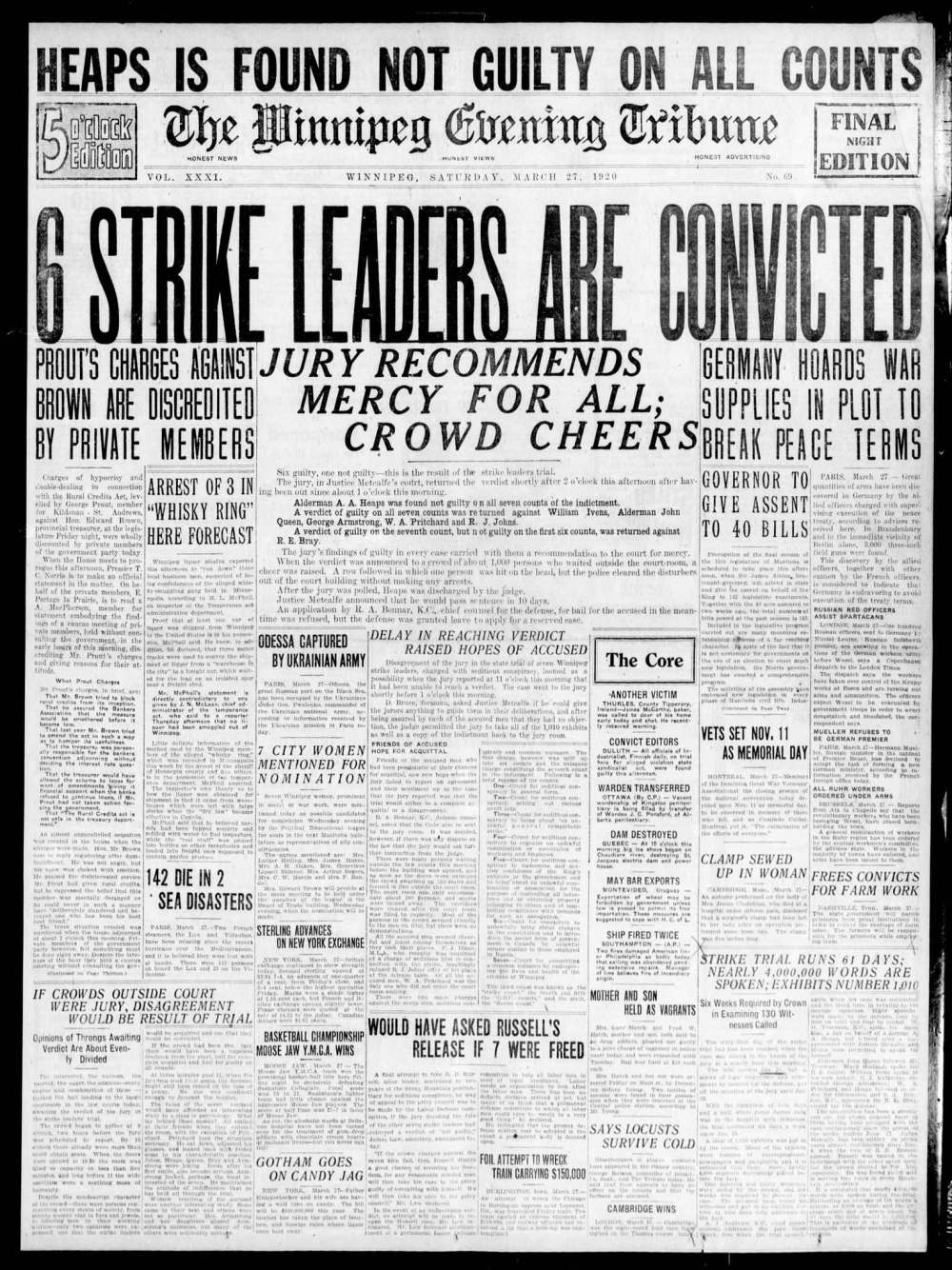

The strike began on May 15, 1919. On June 17, Ivens and other strike leaders were arrested in overnight raids by the police. The strike itself came to an end on June 25, four days after the violence and deaths on Bloody Saturday, when mounted police charged into a crowd of strikers.

Ivens’ church may have played a key role in promoting the strike, but it was opposition from other churches that helped to defeat it. When the strike leaders announced the end of the labour action, they noted it had been overcome by “the forces of capital, the church and state (that had) combined to block the path of progress.”

Charged with sedition, Ivens was found guilty on March 28, 1920, and sentenced to a year in prison. After his release, he ran successfully for public office as a member of the Manitoba legislature before becoming a chiropractor. He died in 1957 and is buried in Elmwood Cemetery.

The Labour Church continued a few more years in Winnipeg before closing. It, like Ivens, is mostly forgotten today. For Reilly, this is unfortunate — Winnipeggers and Canadians should know more about him, he says.

Ivens helped to create and define a better quality of living in Manitoba through his sermons, and his seminal contribution to the community was to make people re-evaluate what their responsibilities are to one another, Butt wrote.

“(He) outlined the glaring inequalities inherent in capitalism and he preached practical reforms.”

“(He was) the bridge between God and the worker on Earth,” Butt continued, offering people a new social order based on the teachings of Jesus.

faith@freepress.mb.ca

The Free Press is committed to covering faith in Manitoba. If you appreciate that coverage, help us do more! Your contribution of $10, $25 or more will allow us to deepen our reporting about faith in the province. Thanks! BECOME A FAITH JOURNALISM SUPPORTER

John Longhurst has been writing for Winnipeg's faith pages since 2003. He also writes for Religion News Service in the U.S., and blogs about the media, marketing and communications at Making the News.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

The Free Press acknowledges the financial support it receives from members of the city’s faith community, which makes our coverage of religion possible.